Cape Town’s drought under the microscope

29 January 2019 | Story Niémah Davids. Read time 7 min.

Research by oceanography student Precious Mahlalela into the cause of Cape Town’s recent devastating drought has earned her the acknowledgment of having a paper published in top international scientific journal Climate Dynamics.

Publication of coursework MSc research in renowned scientific journals is a great achievement, particularly when it addresses such a topical and complex subject, said Professor Chris Reason of the Oceanography Department in the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Faculty of Science.

“We are happy. It’s always gratifying when a student gets a paper published, especially in a leading international journal. One hopes that when they graduate, they will continue making a strong and meaningful contribution to South African research,” he added.

For Mahlalela, a current PhD student, the dearth of published literature on the Western Cape’s rainfall variability was the main reason she dedicated her coursework master’s research project to the topic last year. The fact that the subject directly affects all Capetonians, as well as people beyond the province’s borders, was a bonus.

The Mother City has been gripped by the worst drought in 100 years. While dam levels have improved, and water restrictions were reduced from level 5 to level 3 at the end of 2018, water rationing remains in place. This year Cape Town authorities will focus their efforts on recovery plans and the implementation of initiatives to help the water-scarce city bounce back after it narrowly averted the threat of Day Zero.

“At the height of the drought and panic to avoid Day Zero, the topic concerned all of us. In fact, it still does.

“There are no restrictions and limitations when it comes to who needs water, it affects everyone. Everyone also wants to understand why we find ourselves in this situation,” Mahlalela explained.

“There are no restrictions and limitations when it comes to who needs water, it affects everyone.”

The study

Investigating the Western Cape’s rainfall patterns and linking them to the city’s water shortage was step one, and Mahlalela’s primary focus area.

She analysed station rainfall data obtained from the South African Weather Service for the period 1979 to 2017, surveying four Western Cape regions (the greater Cape Town area, the northern West Coast, the Overberg and the Garden Route) to establish different characteristics in the seasonality of the recent drought when compared to previous droughts.

In particular, and when compared to the full winter rainy season (April to September), Mahlalela’s research found that the early winter drought (April to May) was severe across all regions during the 2015–2017 period.

“Drier winters result from weaker approaching cold fronts, cold fronts steered further south than average, a reduced number of fronts, or all of these factors. A large-scale climate pattern – the Southern Annular Mode (SAM) – when anomalously positive, can cause such changes in cold fronts,” she said.

“It also leads to higher than average pressure over the mid-latitude South Atlantic and a weakening of the westerly wind belt that circles the Southern Ocean.”

Not enough rain

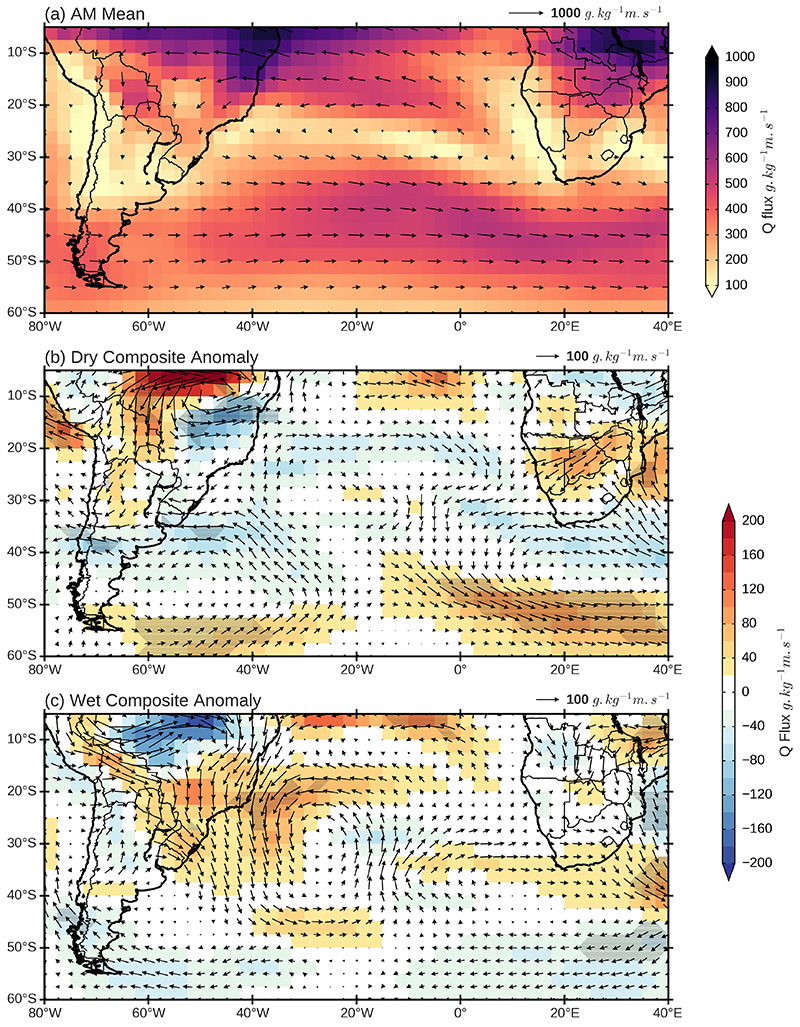

Mahlalela’s research revealed that, in recent decades, the early winter season recorded dry conditions. She explained that this season was associated with a weaker subtropical jet (a belt of strong upper-level westerly winds) during 2015–2017, and less moisture being transported towards the South Western Cape from the South Atlantic.

This, Mahlalela said, was one of the reasons the region received reduced rainfall during recent winters.

“There appears to be a climate change type of signal emerging and we need to increase our planning and become resilient.

We don’t have time to think, we need to act.”

“What happened during 2015–2017 is that both the South Atlantic Anticyclone (a high-pressure system in the subtropical South Atlantic Ocean) and the jet stream were shifted anomalously far south.

“These shifts, together with a tendency of more berg winds over the West Coast, steered the cold fronts further south than average. It resulted in far less moisture to produce rainfall over the South Western Cape, which led to a severe drought.”

Mahlalela’s research also pointed to grave concern about the likelihood of good autumn or early winter rains in the future.

She explained that her investigations of output from climate models used in the Fifth Assessment Report of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) show that prolonged and severe dry periods, as experienced in Cape Town between 2015 and 2017, can be expected in future.

“Although the CMIP5 [Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5] climate models have difficulty in representing the onset of the winter rains in April in the current climate, there seems to be a clear signal of reduced winter rainfall in future, particularly in May and June.”

The way forward

Plan, plan, plan, then act – thatʼs the way forward, she said.

There’s not much time left, and Mahlalela stressed that action to conserve water needs to start now, especially as the population continues to increase and the demand for water grows.

“It all comes down to proper and effective planning and management, together with responsible water usage.”

Water storage and distribution should become a key focus, and not only for the Western Cape. Other Mediterranean climate-type regions such as California, Chile and southern Australia have experienced similar rainfall and water shortage challenges, along with many of South Africa’s summer rainfall regions.

But it’s a unified effort that requires massive collective buy-in, Mahlalela said.

“There appears to be a climate change type of signal emerging and we need to increase our planning to become resilient. We don’t have time to think, we need to act now.”

Mahlalela is already working towards her next research paper, as part of her PhD, which focuses on the ongoing drought in the Eastern Cape.

- Mahlalela, P.T., R.C. Blamey and C.J.C. Reason 2018 Mechanisms behind early winter rainfall variability in the southwestern Cape, South Africa, Climate Dynamics, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-018-4571-y

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.