One for the sardine, two for the birds

10 April 2012If, for a life scientist, the rule of thumb is don't bank on getting your name into the journal Science, like ever, then in 2011 UCT's Dr Lynne Shannon didn't just break the rule, but tossed the rule book out the window.

|

|

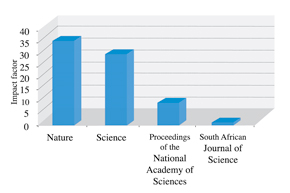

| Teamwork: Dr Lynne Shannon (left) with Dr Yunne-Jai Shin of the French Institute of Research for Development, one of her many collaborators in recent years. | Data: ISI Web of Knowledge, using multidisciplinary sciences as a subject category, and 2010 statistics. The impact factor of a journal is defined as the average number of citations received per paper published in that journal during the two preceding years. |

In August, Shannon, of the Marine Research Institute (MA-RE) and the Department of Zoology, was among the 12 researchers who toasted the publication of a paper - Impacts of Fishing Low-Trophic-Level Species on Marine Ecosystems - in the famed journal, published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. The ink had barely dried on the paper before, in December, Shannon's name graced the journal's pages once again, this time as one of 14 authors of the paper Global Seabird Response to Forage Fish Depletion - One-Third for the Birds.

Science may have one of the shortest names in the world of academic publications, but that's not the reason everyone remembers it. Its impact factor for 2010 was set at over 30 (see graph), making it one of the highest in the world, mentioned only in the same breath as close rival Nature. (One scientist sought for comment described the journal's impact factor, by local standards, as "off the charts".)

As the only common denominator among the two papers' 25 authors, Shannon would have good cause to pat herself on the back. Instead, she puts the achievement down to decades of collaboration, and being in the right place at the right time. That being UCT and, also, Marine and Coastal Management, where she was key in the formation of the South African Working Group on Ecosystem Approaches for Fisheries Management.

These days she also co-chairs the international IndiSeas (Indicators for the Seas) Working Group, which looks at the effects of fishing and natural variability on marine ecosystems. It's a tight-knit group of people who work in this area, says Shannon.

"It's a very small environment, and you generally know everyone in the field."

Everyone, in the case of the first Science paper, meant researchers in Australia, France, Peru, the US and the UK. The nationality net was cast even wider in the second group, made up of scientists from Canada, France, Namibia (including UCT colleague Jean-Paul Roux of the Animal Demography Unit), Norway, South Africa, Sweden and the US.

But the Science editors and referees were probably more impressed by the findings than the panorama of passports.

Despite looking at five far-flung ecosystems - in Peru, the North Sea, South African waters and the Southern Ocean - though there was variability, there was a clear and common pattern across the first study, which covered the impact on those ecosystems of potential over-fishing of low-trophic-level species, aka forage fish, such as anchovy, sand eels, sardines and krill. (These fish are key in the food web as they are the 'middlemen' between plankton and a whole suite of larger, predatory fish, mammals and seabirds.)

Such was the common ground that the authors could even come up with specific numbers in their paper, applicable across the ecosystems. Halving exploitation rates, they concluded, would result in much lower impacts on all the marine ecosystems in question, while still achieving 80% of maximum sustainable yields, thus not crippling the systems' fishing industries.

Similarly, the second band of researchers found mutual features. In that study on the impact that the depletion of forage fish would have on seabirds, they identified a threshold in prey abundance (ie the number of forage fish) below which breeding success - defined as chicks fledged per breeding pair - took a substantial dive; and at which breeding patterns were more unstable and unpredictable. "This response," the researchers wrote, "was common to all seven ecosystems and 14 bird species examined within the Atlantic, Pacific and Southern Oceans."

(Per the 'one-third' in the paper's title, they advised that, as a general guiding principle, the threshold of one-third of maximum observed fish biomass is an indicator of the minimum level of fish needed in the ocean to sustain long-term seabird productivity, and probably ecosystem sustainability, in the broader sense.)

These findings, more than getting her name into Science twice in quick succession, are what Shannon treasures most. She's found that such universal findings across international boundaries and ecosystems come in handy when it comes to shaping local policy.

"Proposals are more respected when they come from such a broad group," she says. "And in the end it's not about getting into Science, but about seeing that your work is useful."

For the record, a third paper for the journal may well be on the horizon.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.