UCT’s first black medical doctor remembered

09 September 2022 | Story Helen Swingler. Photos Lerato Maduna. Voice Cwenga Koyana. Read time 6 min.

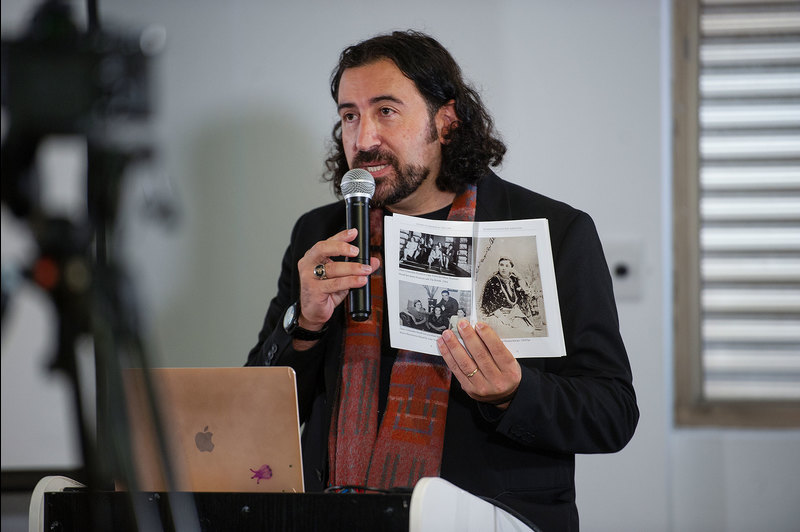

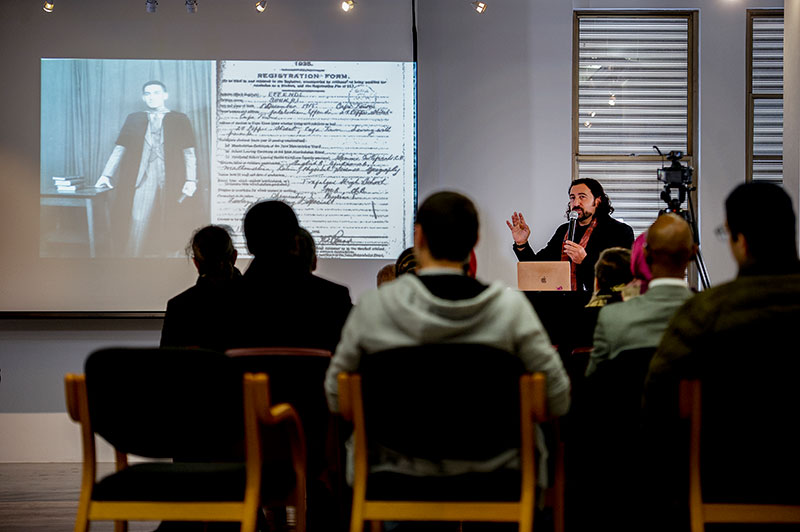

The early death in 1946 of the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) first black medical doctor, Dr Muhammed Shukri Effendi, may have contributed to his obscurity in the South African historical archive, said UCT Ottoman scholar Dr Halim Gençoĝlu. He was speaking at a seminar to mark the 76th anniversary of Dr Effendi’s death.

The seminar was titled ‘White Skin, Black Destiny: UCT’s first black medical doctor Muhammed Shukri Effendi’.

It was previously thought that Maramoothoo Samy-Padiachy, Cassim Saib and Ralph Lawrence, who graduated in 1945, were the first black MBChB graduates from UCT. But Dr Gençoĝlu’s interest in Turkish–Ottoman links to the country and his ardent sleuthing in the UCT, South African and Turkish archives showed otherwise. Gençoĝlu is a postdoctoral research fellow in the Department of Sociology’s Re-Centring Afro Asia Project.

Held in the Centre for African Studies Gallery on 2 September, the seminar was attended by the Turkish Consul-General, Sinan Yeşildağ; an Imam from Istanbul, Abdullah Kılıç; and leading figures in the Muslim community. These included Hesham Neamatollah Effendi, Dr Effendi’s nephew.

The event also highlighted the Faculty of Health Sciences’ 110th anniversary this year.

Born in Cape Town in 1915, Effendi qualified as a doctor at UCT’s medical school in 1941, graduating in 1942. Given the racial politics of the time, the fair-skinned student’s origins and religion seem to have been overlooked when he registered at UCT in 1925, said Gençoĝlu.

Sadly, Effendi died of tuberculosis at the age of 30 at his family home, Ezeroum, in Woodstock, where he’d practised after a brief stint at Groote Schuur Hospital. But he should not be forgotten, Gençoĝlu said at the seminar. Effendi is one of several members of the Turkish–Ottoman-descended community in South Africa who have contributed to and enriched the country’s diverse culture and history.

Other discoveries

Other important discoveries are linked to Turkish–Ottoman presence in South Africa. Gençoĝlu’s research also showed that the first black woman doctor to practise in South Africa was Effendi’s cousin, Dr Havva Khayrunnisa. Dr Khayrunnisa graduated in London in 1920. She came to Cape Town to practise after her husband died in 1929.

Gençoĝlu also found that South Africa’s first aviator of colour was Muslim Rushdu Atala. Atala was a cousin of anti-apartheid and civil rights activist Zainunnisa “Cissie” Gool, after whom UCT’s Cissie Gool Plaza is named.

It was Gençoĝlu’s tireless and thorough research that first brought Effendi’s achievement at UCT to light in 2016. Through his links with Emeritus Professor Anwar Mall (Division of Surgery), the discovery led to the faculty changing their historical records to reflect the facts.

Speaking at the seminar, Emeritus Professor Mall recounted how he’d met Gençoĝlu in the corridors of the medical school, outside his office. The history scholar had been engrossed in the old graduating class photographs displayed there.

After introducing himself, Gençoĝlu had dropped a bombshell, said Mall. The trio of doctors, Maramoothoo Samy-Padiachy, Cassim Saib and Ralph Lawrence, were not UCT’s first black doctors, he said.

“I got a shock,” Mall said. “I asked, ‘Are you sure?’… We’d had a huge celebration to let the world know our first three black doctors graduated in 1945. But to cut a long story short, the matter was corrected.”

Follow the evidence

However, it raised questions about the perniciousness of apartheid, said Mall, whose career at UCT spanned 40 years and included a stint as acting deputy vice-chancellor for Transformation and Student Affairs.

“He didn’t create a rumour or stay silent. He made a study and found the evidence.”

“Effendi, who would have been classified as Malay, Asian or coloured during the apartheid dispensation, was taken into UCT because he looked white … And this is a lesson for us that any kind of discrimination, any kind of racism, is vile.”

In pursuing the truth, Gençoĝlu had behaved like a true scholar, Mall said.

“He didn’t create a rumour or stay silent. He made a study and found the evidence.”

Herein lie important lessons about the value of learning in a world where the value attached to learning is threatened, said Mall.

“It is time to recognise Dr Effendi by naming one of the buildings at the UCT medical school after him.”

“We live in an age where even in first-world countries attitudes towards learning are changing. People are joining woke movements, people are joining a cancel culture … But education and truth are meant to offend. It opens your mind. And Halim represents this kind of thinking.”

Gençoĝlu has also called for the Faculty of Health Sciences to acknowledge Effendi more formally.

“I believe it is time to recognise Dr Effendi by naming one of the buildings at the UCT medical school after him. That is one way we can substantially rectify a historical misconception and honour one of the forgotten heroes in South African history,” he said.

“This would also encourage other relevant studies in the context of decolonisation. I hope UCT will rally to the call.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.