‘Master historian’ reflects on UCT’s history

14 February 2020 | Story Carla Bernardo. Photos Lerato Maduna. Read time >10 min.

What is university history? Is it the history of teaching and research, a changing intellectual climate or a breakthrough in ideas? Is it about the lecturers or the learners or those who direct the institution’s operations? Or is it about the relationship between society and the university and how it fits into a country’s system?

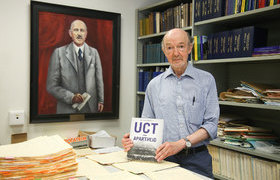

According to master historian Emeritus Professor Howard Phillips it is all of this and more – it is a “hybrid subject”.

Speaking at the launch of UCT Under Apartheid: Part 1 – From onset to sit-in, 1948–1968, Phillips took a packed room through highlights of the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) educational, institutional, architectural, social and political history.

The launch and lecture, which were hosted by the retired academic’s publisher, Jacana Media, and UCT’s Development and Alumni Department, took place on Wednesday, 12 February.

To bring the book and this period of history to life, Phillips and his research assistants – Ms Lesley Hart, Dr Farieda Khan and Dr Neil Overy – spent five years trawling written sources, numerous libraries, special collections, government publications and archives, UCT Libraries, and the treasure trove that is UCT Archives.

The team also conducted over 200 interviews with former staff and students, and searched through some 50 000 photographs, cartoons and sketches, eventually whittling it down to 122, which are published in the book.

UCT Under Apartheid follows The University of Cape Town 1918–1948: The formative years. In this most recent volume, Phillips explores the operations of UCT, its construction, its interaction with the wider community, its “fraught relations” with the apartheid state, students, and the core business of the university – teaching, learning and research.

In introducing the emeritus professor, Dr Bodhisattva Kar, head of UCT’s historical studies department, said he couldn’t “think of a more qualified and a more courageous historian to undertake this daunting task of writing the apartheid-era history of this institution in these embattled times”.

“It requires a kind of quiet courage, of which all who know Howard, know that he has plenty.”

Gems and aims

While conducting research for UCT Under Apartheid, Phillips and his research assistants discovered a number of hidden gems in the archives. One of these was handwritten speech notes by former UCT vice-chancellor Thomas Benjamin Davie – a champion for academic freedom.

In it, Davie listed the key elements he had formulated in 1950: who teaches, what is taught, how it is taught and to whom it is taught. Then, Davie wrote, “Valued highly: staff and students rise up in arms if freedoms threatened. The university is dead where the students fail to fight for these rights, both for themselves individually and for their student associates in other universities. The heritage of the universities of the Western democracies. He who pays the piper calls the tune only if he knows what tune to call.”

While Phillips could not establish whether Davie delivered the speech exactly as indicated in his notes, this discovery, said the historian, built on Davie’s original concepts and revealed the development of the former vice-chancellor’s ideas as apartheid tightened its grip on the country.

In addition to examining the 20 crucial years in UCT’s history, Phillips stated that there were three further aims in shaping this book.

“I want to make it very clear that this is a period of very significant transformation of the university in intellectual and academic terms.”

The first was to alert a wide array of readers to the fact that between 1948 and 1968 UCT changed rather dramatically from being a teaching institution to being both a teaching and research institution. Today it sees itself as a research-led university. This claim, said Phillips, underpins UCT’s current status as Africa’s top university.

“And I want to make it very clear that this is a period of very significant transformation of the university in intellectual and academic terms,” he said.

The second aim was to “flag the ups and downs” of what Phillips called “the beginnings of indigenisation of teaching and research”.

“Perhaps it’s a pre-precursor or pre-pre-precursor of what is perhaps now known as decolonisation,” said the historian.

While the process has accelerated markedly in the last decade, said Phillips, it is important to note that in the 1950s and 1960s there was some indication of attention being given to UCT as an African university and not simply an outpost of Europe.

The third and final aim was to have UCT come to terms with its “mixed record” under apartheid.

UCT and apartheid

One of the chapters in the book deals with UCT’s “fraught” relationship with the apartheid regime during the period covered. Tellingly, the chapter is titled “Colliding and colluding”.

Phillips provided attendees with multiple examples of this: There was the arrival of the official Holloway Commission into establishing racially separate universities. In response, students made it clear that they did not want university apartheid.

There was another example shown and discussed by Phillips – this time of three students speaking at a 1956 mass meeting in Jameson Hall (now Sarah Baartman Hall). These three students were all protesting against apartheid, but their subsequent careers were significantly different: Neville Alexander went on to join the National Liberation Front and was a political prisoner on Robben Island; Neville Rubin (who was present in the audience at the launch and shared his memories of marching against apartheid as a UCT student) joined the Liberal Party and the Defence and Aid Fund in the United Kingdom; and Dennis Worrall, who subsequently joined the National Party and became an MP and then South Africa’s High Commissioner in London.

“Moving forward requires a knowledge of how the present was reached.”

Phillips presented archival images of a mass march by students and staff in 1957 and 1959 and an image of UCT student Adrian Leftwich holding the extinguished “torch of freedom” outside Parliament, supported by Chief Albert Luthuli, then president of the African National Congress.

Of course, there was also the 1968 sit-in at the Bremner Building in protest against the UCT Council, which had decided to reverse the appointment of Archie Mafeje as senior lecturer in social anthropology. There was also discussion about segregated ward rounds; “apartheid after death”, where black students could not view the post-mortem of a white person; and the use of black workers as a physical barrier between protesting students and apartheid’s Jan Haak who was invited to open UCT’s Snape Building.

For Phillips, these provide UCT with an opportunity to reflect: “UCT has, I think, to recognise its role and its … mixed relationship with policies of apartheid and apartheid government. Until UCT has recognised both its beauty spots and its warts and confronted them directly, it will not easily be able to go into the future unequivocally.”

“As I say in the preface to the book,” concluded Phillips, “moving forward requires a knowledge of how the present was reached, bearing what baggage.”

In his thanks, Phillips acknowledged Dr Kar, his predecessors as heads, and the Department of Historical Studies for their “interest, enthusiasm, technical support, all in abundance”; UCT’s Council for funding the UCT history project and, in particular, former Council member Mr Justice Ian Farlam for “championing the project through thick and thin”; registrars Hugh Amoore and Royston Pillay, who, with their staff, facilitated the administration of the project; the Development and Alumni Department and Jacana Media for organising the lecture and launch; the Special Collections division of UCT Libraries and the Digital Library Service; UCT Archives’ Lionel Smidt and Stephen Herandien, who were “pillars of well-informed assistance”; his research assistants for their “sterling research”; his “meticulous editor” Russell Martin and indexer Tanya Barben; and, finally, his wife Juelle and their children, Laura and Jeremy, for the “unstinting support, both direct and indirect”.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.