Betrayal of the 'Great Unwashed'

26 August 2015 | Story by Newsroom

Thembinkosi Gwelani was fleeing from police at 'Scene One' of the massacre at Marikana on 16 August 2012, when he was shot with a single bullet from a semi-automatic rifle. Gwelani, 37, was one of two fleeing miners who were fatally shot in the back of the head from a distance of 250 metres away that day.

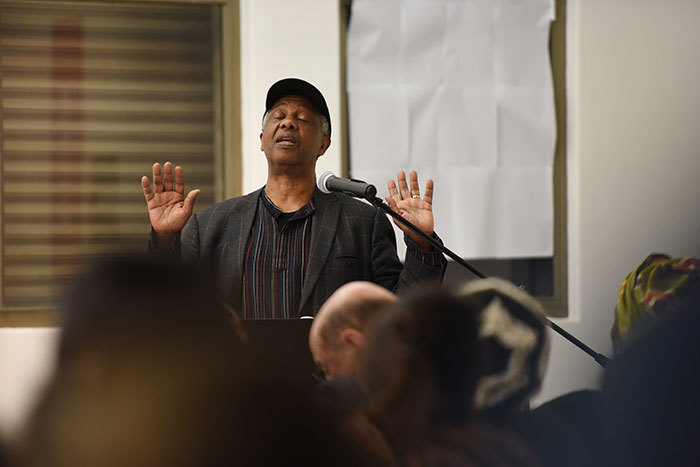

They were deemed to have been "accidentally killed" by Judge Ian Farlam's report, said Advocate Dumisa Ntsebeza, who delivered the second annual Marikana Memorial Lecture on 20 August.

Titled "The Marikana Report: Betrayal of the 'Great Unwashed'", Ntsebeza's lecture unpacked the Farlam Report from his perspective as the lawyer for the families of the slain mineworkers at the commission of inquiry.

Ntsebeza pointed to a number of seeming inconsistencies in the way Farlam linked evidence to conclusions, often in a way that alluded to a "structural bias" against the mineworkers.

For instance, he expected the commission to conduct a "body by body" account of the miners' deaths. But commissioners resisted appeals to read pathology reports on the miners' bodies, saying the reports should be considered read. Ntsebeza and company insisted on a body-by-body analysis of the killings, but encountered reluctance from the commission.

It was the opposite for attacks on police, which in some cases were recounted in minute detail, with portions of a statement that portrayed black men as "sex-crazed, violent and savage" finding its way into the report sans a line of interrogation. Ntsebeza found this a "dispiriting dereliction of the commission's duty".

Another example was the commission's conclusion that the strikers "were so violent that the police had reasonable grounds to conclude that they were under attack which justified them defending themselves and their colleagues".

Police were subsequently let off the hook en masse without hearing a single piece of evidence from the tactical units who fired the shots.

"Yet the commission rightly noted that from the outset the senior police closed ranks, that they orchestrated a fabricated account, that they concealed evidence and systematically lied to the commission."

The police case was that no order was given to fire on the workers. But Ntsebeza pointed to evidence that an order to fire on the workers was, in fact, given.

"The commissioners side-lined evidenced from a Lonmin executive who gave an order to fire on the workers," he said. "Engage; engage; engage". These words were followed by a hail of machine gun fire. That evidence was not given by mineworkers, but by Lonmin security, said Ntsebeza.

Hours before the memorial lecture, UCT students and staff marched from Bremner building to Jameson Plaza to commemorate the dead workers.

Hours before the memorial lecture, UCT students and staff marched from Bremner building to Jameson Plaza to commemorate the dead workers.

Nobody to blame?

After 300 days of hearings and R157m of public money, the commission merely recommends further investigation, said Ntsebeza. He lamented the no-show of Phase Two of the commission, which would have delved into the socio-economic circumstances that might have contributed to the strike and the massacre.

A lot of what caused the massacre was the "decided policy" of Lonmin and the police to safeguard the interests of capital and that this was going to be done at any and all costs, he said. But the closest the commission got to apportioning blame was to paint the strikers' conduct as, essentially, asking for it.

Ntsebeza quoted a key paragraph from the report: "The tragic events that occurred between 12 and 16 August 2012 originated from the decision and the conduct of the strikers in embarking on an unprotected strike and in enforcing the strike by violence and intimidation using dangerous weapons for the purpose."

Having considered the evidence, Ntsebeza draws a different conclusion: "The miners begin to see a build-up of police numbers from 209 on the 13th, 542 on the 14th, to 689 on the 15th, and 718 on the 16th. They see warlike heavy weapons ... rumbling into Marikana. The commission should have concluded from the evidence that the mineworkers must have been terrified, that they were brutally attacked and killed by a combination of police and Lonmin security."

He couldn't help but notice that "those in power are exonerated", and that the "whole truth about the Marikana massacre", if ever it was going to emerge, was not to be found in this report, which Ntsebeza said did more to recommend further investigation than anything else.

"In other words, there is no one to blame."

'They thought this was going to go away'

Ntsebeza's brother is the Professor Lungisile Ntsebeza, the AC Jordan Chair in African Studies at UCT. On 24 September 1985, their cousin Batandwa Ndondo was shot to death in broad daylight in an unprovoked attack by apartheid police.

"They thought this was going to go away," said Ntsebeza, before noting that 30 years later Ndondo's murder was still remembered. "There's no way anyone can think the memory of those killed at Marikana will fade."

Ntsebeza explored some of the reasons the mineworkers went on strike that year.

Abject living conditions meant the "miners often felt a deep sense of humiliation and disrespect," said Ntsebeza. The 2012 strike, therefore, became both an attempt to secure a bigger pay-packet and a symbol of the struggle to regain a "sense of belonging" in a post-apartheid South Africa, he said.

The 'Great Unwashed'

Lawyer Jim Nichol represented the dead workers' families at the Farlam Commission. Ntsebeza related Nichol's alternate phrasing of one of Farlam's defining conclusions.

"If the attitudes of the commissioners were not shaped by what the commissioners thought of the 'Great Unwashed' of Marikana, then they would have the courage to substitute the current paragraph 1.1(b) of Chapter 3 of the Farlam Report with the following: 'The tragic events that took place between 10 and 16 August 2012 originated from the decision and conduct of Lonmin. The company embarked on an intransigent policy of refusing to discuss with the mineworkers their grievances. They enforced this policy by encouraging the SAPS to break the strike knowing that death and serious injury would likely result from the SAPS' use of dangerous weapons.'"

Everyone Ntsebeza cross-examined, including political leaders, agreed with him that the Marikana massacre was something that should not have happened and should not happen in the future.

"There is of course a divergence of views between the leaders of our democracy and the 'Great Unwashed' as to how this should happen."

Ntsebeza closed with a quote from Urban Dictionary: "Corporations fear the day that the great unwashed will throw off the shackles of consumerism and ever-increasing debt and focus on more important endeavours such as their health, family and friends."

Story by Yusuf Omar. Photos by Je'nine May.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.