Inequality: what Brazil got right

13 November 2014 | Story by Newsroom

Ask a random sample of South Africans what the major illness affecting the economy is, and inevitably, the word 'inequality' comes up. But a comparison between the contrasting trajectory of inequality in two developing countries - South Africa and Brazil - highlights some pretty alarming findings.

Those who live in these shanty towns prefer its prime location next to the city centre, as they can earn a living being close to the city.

When South Africa became a democracy in 1994, the average child spent about seven years in school. Across the Atlantic, in Brazil, a country that was also emerging from years of authoritarianism, the average child spent only about five years in school.

Within three years, the two new democracies both began to invest heavily in social welfare, health and education. Within a decade, the average South African child spent 10 years in school; in Brazil the climb was less dramatic, from five to seven years.

In both countries, social welfare, old-age pensions and child-support grants began to lift the poorest out of the most intense poverty. In Brazil, unlike in South Africa, those grants were conditional on school attendance and enrolment at clinics.

Both countries are big spenders on education, and there has been enthusiastic uptake of education in South Africa, even though it is not tied to social grants.

And yet the inequality gap widened in both countries. By the year 2000, Brazil and South Africa had the dubious distinction of being the most unequal societies in the world.

Then, in Brazil, the story began to change.

Last month the results of research were presented at a United Nations University conference on inequality in Helsinki, Finland, comparing the distribution of schooling with the distribution of earnings - in Brazil from 1976, and in South Africa from 1994. The researchers were from the University of Cape Town's Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit, working under the ambit of the Research Project on Employment, Income Distribution and Inclusive Growth.

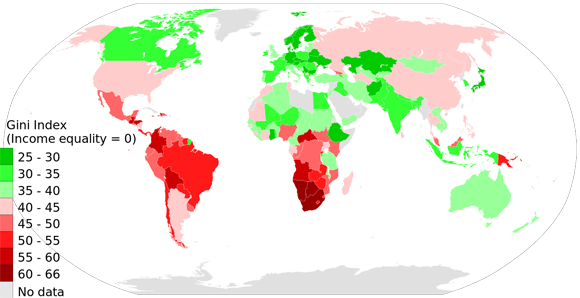

The Gini index is a measure of income inequality. A nation where every individual's income is equal would have a gini index of 0. A nation where one individual gets all income, while everyone else gets nothing would have a gini index of 100. Higher gini index for a nation means more income difference between its people.

The average of Gini index scores in this map is about 40. All countries color coded in green have gini index scores less than 40, while those in shades of red have gini index above 40.

The findings were remarkable. Today, a child in Brazil goes to school for an average of seven years, bringing schooling to the same level South Africa was on 20 years ago.

But earnings inequality has decreased in Brazil - and increased in South Africa.

Both countries underwent macro-economic stabilisation programmes in the mid-'90s to stem rising debt costs and to counter financial instability. In both countries, these policies were unpopular with powerful interest groups.

Perhaps Brazil was luckier, because shortly before former president Fernando Cardoso introduced the REAL policy (named after the currency) to stem an inflation rate of over 2000%, Brazil won the soccer World Cup, and national celebrations overshadowed the protests.

There was an element of luck, too, in Brazil's ability to narrow the earnings gap. Brazil grew at a rate of between five and seven per cent in the early 2000s - not 'China' fast, but at a higher rate than South Africa's best growth.

More importantly, Brazil improved its exports, particularly in industries such as agro-processing. Many of those industries required semi-skilled labour, and fortuitously, some of them were located in more remote parts of Brazil that had previously been marginalised.

The knock-on effect was that because semi-skilled labour was valued, the returns to those with basic schooling started to increase.

Rocinha Favela: This is one of the largest shantytowns in South America with over 200,000 inhabitants. There are many such slums alongside modern high rise buildings, in cities of Brazil.

At the Helsinki conference, Brazilian minister and economist Marcelo Neri reported that in the past 12 years, the income of the poorest five per cent of the population had grown more than five times as fast as the income of the richest five per cent. In the 1990s, Brazil laid the platform for inclusive growth, and then used the opportunity, when it came, to increase living standards and bring down inequality.

So what went wrong in South Africa? We laid a similar platform in the 1990s, but our story did not take this virtuous turn in the 2000s. The earnings of those with tertiary education have continued to increase strongly, and are often three times as high as for someone who only has matric. And those who have matric are likely to have earnings 50 per cent higher than people with less schooling.

The difference is stark: just a few years more of schooling in Brazil had an equalising effect, but in South Africa, a much bigger increase in years of schooling has not turned the tide of rising inequality.

It's true that Brazil may have been lucky that world demand for agricultural exports grew in the early 2000s. In South Africa, in the same period, the agriculture sector shrank, shedding 1.5 million jobs.

So what to do?

There are no easy answers. Minimum wages were implemented in Brazil, and played a part in increasing the earnings of semi-skilled workers. But in the end, it was strong economic growth and the pattern of that growth that created jobs for these workers.

In South Africa we also have minimum wages: the big difference is, we don't have the jobs.

Brazil shows that one key to a more equal society is to give better returns to those with basic school education. This can only be done sustainably by improving the quality of basic education, by creating jobs that absorb semi-skilled people, and by increasing the supply of skilled people.

We may not be able to emulate Brazil and its success in agro-processing industries, but we must be able to find a way of valuing those who enter the labour market with basic schooling by strengthening big and small businesses, or through the informal sector.

And we must provide our young people with an education that enables them to read, write, count '“ and yes, work.

Leibbrandt is director of the Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit. Green is a communications consultant on the research project.

Story by Professor Murray Leibbrandt and Pippa Green. First published on Times Live and in Sunday Times Business Times.

Gini Index World Map sourced from Wikimedia Commons under Creative Commons 3.0 license.

Photograph of Rocinha Favela sourced from Wikimedia Commons under Creative Commons 2.0 license.

Photo of Brazilian girl sourced from Wikimedia Commons under Creative Commons 2.0 license.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.