Custom or crime - a thin line

26 August 2013 Dr Elizabeth Thornberry is Assistant Professor of History at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the Centre for Law and Society.

Dr Elizabeth Thornberry is Assistant Professor of History at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the Centre for Law and Society.

Balancing the rights of young women against culture is a complex issue, says Dr Elizabeth Thornberry

The cases of ukuthwala that have seized public attention over the last few years involve the violent abduction, and sometimes rape, of girls as young as 12 by older men. In addition to being illegal under criminal law, these abductions have been criticised by some scholars and traditional leaders for distorting the 'real' custom of ukuthwala. Such criticisms allow advocates of custom to disavow these sensational cases without undermining the broader goal of both supporting customary law and - for traditional leaders - asserting their own right to decide what counts as custom and what does not. However, the current practice of ukuthwala is accepted as customary by some local communities, thus meeting the definition of living customary law as recognised by the Constitutional Court. Ukuthwala cases remind us that even living custom must still be developed to comply with the Constitution.

Academics sympathetic to African customary law have described the normative practice of ukuthwala. as a fake abduction, in which a young woman would pretend to resist even though she had actively planned the marriage with her future husband. In this view, the problem with current ukuthwala practices is that these are forced marriages, taking place against the will of the young women concerned. By contrast, in the 'correct' form of ukuthwala, young women merely feign their unwillingness to marry.

This critique glosses over any potential conflict between the rights of the young woman and the right to culture. The 'true custom', as practised in the past, is carefully distinguished from the current, exploitative practices. While this view is appealing, it does not grapple with the fact that the Constitutional Court grants legal recognition to custom based on current local practices rather than on historical norms. As a result, it gives no guidance on how to handle practices that are locally accepted as customary while at the same time being harmful to children, women, or other vulnerable groups.

Major representatives of traditional leadership in the Eastern Cape have offered their own critiques of recent cases of ukuthwala. Xhanti Sigcawu, a member of the Xhosa royal family and a representative of the Congress of Traditional Leaders of South Africa (Contralesa), differentiated between ukuthwala properly practised and kidnapping. The proper practice, he said, is when "the families of the young man and the girl would meet and negotiate...[and] reach an arrangement", but it is kidnapping "when a husband takes a woman without interaction with her parents". Nangomhlaba Matanzima, chairperson of the Eastern Cape House of Traditional Leaders, complained that "they are taking children from 13, 14...that is not ukuthwala, that is not a custom. You can't go for the little ones". In these critiques, the problem with ukuthwala is not the young woman or girl's lack of consent, but rather the failure to gain the consent of the family or the breaching of the culturally appropriate lower boundary on the age of marriage.

The advantage of this line of argument lies precisely in its avoidance of the issue of women's consent to marriage. Traditional leaders can condemn a practice that garners negative publicity and threatens to taint the entire realm of custom, without undermining a broader claim to the authority of household heads over their dependents. These claims must also be understood - at least in part - as an assertion of the authority of traditional leaders to make decisions over what counts as proper custom and what does not. Such assertions protect young girls against ukuthwala but at the price of confirming the power of families to control the sexuality of their daughters and of traditional leaders to set the terms of custom.

On the other hand, members of families implicated in ukuthwala cases, as well as some (certainly not all) other residents of Eastern Cape communities where the practice is prevalent, claim that ukuthwala as currently practised is indeed customary. Ncedisa Paul, who works for a local health non-governmental organisation, told the Daily Dispatch that "people say that's just the way it is - it is part of their culture, they say." Members of local communities in the Lusikisiki area seem to agree that the current practice of ukuthwala is customary, and has longstanding roots. In Cele village, for example, the Dispatch also quoted 81-year-old Nyekelwa Cebe saying that "during our time we competed for women, and if one procrastinated, the girl would be grabbed by the other family."

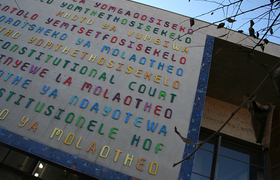

For activists who have dedicated themselves to defending local interpretations of customary law against attempts to allow chiefs to define custom, or to continue to enforce apartheid-era interpretations of custom, ukuthwala cases present a problem. Living customary law seems to condone the violence that is being done to the victims in these cases, while more authoritarian versions of custom offer at least some protection. These cases should remind us that all sources of law - including both common law and customary law - must still be interpreted and developed in light of the Constitution. While living custom provides an important source of law for millions of South Africans, it is subject to the same protections that the Constitution provides for all South African citizens. Respecting custom should lead us to embrace the development of customary law, so that all South Africans may enjoy the equal protection of the Constitution.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.