Artist captures diaspora of children

03 October 2005

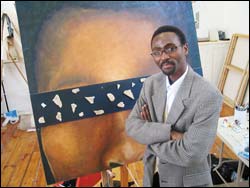

Give them bread: "Art is a product of its time. It must address the issues of society. If it doesn't it is dead." - master's student Wandile Kasibe.

In Nigeria they are known as almajiri. In Senegal they are talibé. In Mali and Burkina Faso they share a name: garibou. In Malawi they are amasikini.

Further south, in Johannesburg, they're called malalapayipi, "sleepers in pipes". In Cape Town, they're known as strollers. In Zulu, the word is malunde, a reference to a diaspora, "those who went to the streets".

All are names for street children - a problem in any language.

Street children were recorded in South Africa for the first time in 1908. They are the fallout of civil war, natural disasters and social fragmentation - and also the focus of master's student Wandile Kasibe's artworks and thesis, titled Malunde and the Diaspora.

As part of his Harry Crossley Foundation research scholarship, he held a seminar on the topic, gathering social workers and artists to discuss responses to the diaspora.

As an artist, or "visual practitioner" as he prefers, Kasibe's own response is visual. In his studio at the Michaelis School of Fine Art, his works are larger than life; faces of street children, eyes blacked out by a row of stale bread.

In another, toy guns reflect the aggression and force used to kill street children like Xolani Jodwana, the 17-year old shot dead outside Teazers club.

He wants street children to be seen within their political and social context.

"Bread is one part or element reflecting the notion of begging. Please feed me. It challenges us. How will we respond?" he asks.

In his work, there is a sense of their identities having been shuttered, and Wandile feels this is exactly the way society sees them.

"Their identities are hidden by a veil of homelessness."

Kasibe has strong views on this and believes artists have a unique role to play in social justice.

"Art is a product of its time. It must address the issues of society. If it doesn't it is dead."

Orginally from Mdantsane in the Eastern Cape, life could have been very different for Kasibe. He remembers pushing trolleys for small change and working in taxis after school, smoking dagga on the streets of East London. The street children of Cape Town have revived those memories.

"The whole phenomenon of street children is connected to the past that faces us today. But as a society, we don't want to know. We treat the kids like animals."

Extending a hand, Kasibe began teaching drawing to street children frequenting the byways behind parliament. He encourages them to draw; to tell their stories through images.

Kasibe also visits shelters and conducts workshops.

Their drawings are rough, with strange things, "enigmatic features and sharp lines". But, significantly, he was amazed to see their depiction of themselves against the foreground of Table Mountain.

"They see themselves connected to the beauty of the city."

Eventually, Kasibe wants to hold an exhibition of their work.

"These kids aren't given a chance to express themselves; they're marginalised; pariahs."

But like many, Kasibe cannot see a solution to the problem.

"Where do we locate displaced children? I am grappling with these questions in my paper. I blame the system and the black community for not protecting these children."

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.