Brain gain

15 November 2019 | Story Ambre Nicolson. Read time 8 min.

The University of Cape Town (UCT) Neuroscience Institute is designed to be comprehensive in nature and cross-cutting in function. This distinguishes it from similar institutes in the global north and makes it possible for experts in a range of fields to come together to better understand African challenges: the interplay between the brain and conditions like trauma or infection, and its consequences for brain development and function.

In 1979, former UCT professor and physicist Allan Cormack won the Nobel Prize in Medicine for inventing CT (computerised tomography) scanning. Now, 40 years later, the same building where Cormack worked houses a new institute dedicated to the human brain.

“The idea of a Neuroscience Institute at Groote Schuur Hospital was a longstanding dream of pioneers such as Professor JC ‘Kay’ De Villiers and Professor Roland Eastman, but the real work to establish the centre began around 10 years ago,” explains Professor Graham Fieggen, director of the UCT Neuroscience Institute and Mauerberger Chair of Neurosurgery.

“Having a centre which offers truly multi-disciplinary training and the chance for patients to be assessed in a holistic way is very exciting and a first for Africa.”

Fieggan is a passionate advocate for, in his words, “doing away with false compartmentalisation when it comes to the human brain”.

“While there has been a tendency for clinicians and researchers to get stuck in the perspective of their training, whether that was neurology, neurosurgery or psychiatry,” he says, “it is important to remember that we are all treating the same brain.

“It is therefore essential to give the next generation of specialists a much broader understanding of the brain.”

According to Fieggen this is one of the characteristics which sets the Neuroscience Institute apart from other such facilities. “Having a centre which offers truly multi-disciplinary training and the chance for patients to be assessed in a holistic way is very exciting and a first for Africa.”

Matthew Wood, a UCT alumnus and professor of neuroscience at the University of Oxford, believes that the institute is unique. “It combines clinical excellence with deep expertise in major areas of neuroscience, such as brain infections, which are a high priority for African and developing-world populations.

“This, coupled with a special focus on paediatric populations, means that the Neuroscience Institute will, in time, make a powerful contribution to global neuroscience.”

Breadth of brain research

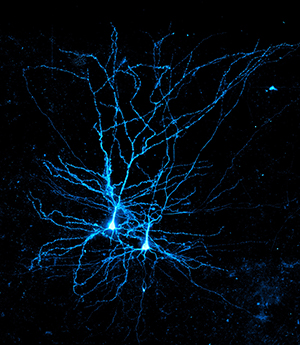

Another defining characteristic of the Neuroscience Institute is the breadth of its research. In addition to offering a postgraduate programme and specialised professional training, the institute’s members are involved in broad-ranging research related to the brain.

“There is a huge array of work being done: in the community and clinics through to operating theatres and the laboratory,” says Fieggen. “These vary greatly: from the UCT-led Drakenstein Child Health Study – a multi-year study of 1 000 mother-child pairs to investigate the role and interaction of a range of risk and resilience factors – to intensive monitoring of the brain to improve recovery from injury and development of new surgical techniques. One example is work done by Professor Darlene Lubbe and her team at Groote Schuur Hospital, to access brain tumours via the eye-socket.”

Other areas in which the Neuroscience Institute hopes to build on a strong research foundation are neuro-infection – diseases that affect the nervous system, such as meningitis and encephalitis – and early brain development.

UCT Professor Kirsty Donald explains that explosive population growth in Africa could mean that by 2050 a large part of the population will be younger than 18 years.

“There are few places in the world that combine deep expertise with insight and understanding of these populations.”

“This growth represents huge potential,” says Donald, a paediatric neurologist and deputy director the Neuroscience Institute. “But it also means that we must urgently understand how best to support healthy brain development in children, particularly those children who live in high-risk contexts and places in which they are exposed to infections like HIV.

“There are few places in the world that combine deep expertise with insight and understanding of these populations.

“The UCT Neuroscience Institute is one place where this is possible, thanks in part to the special relationship that the university enjoys with the Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital as a teaching facility. The Neuroscience Institute represents an enormous opportunity to improve people’s lives.”

Transforming neuroscience

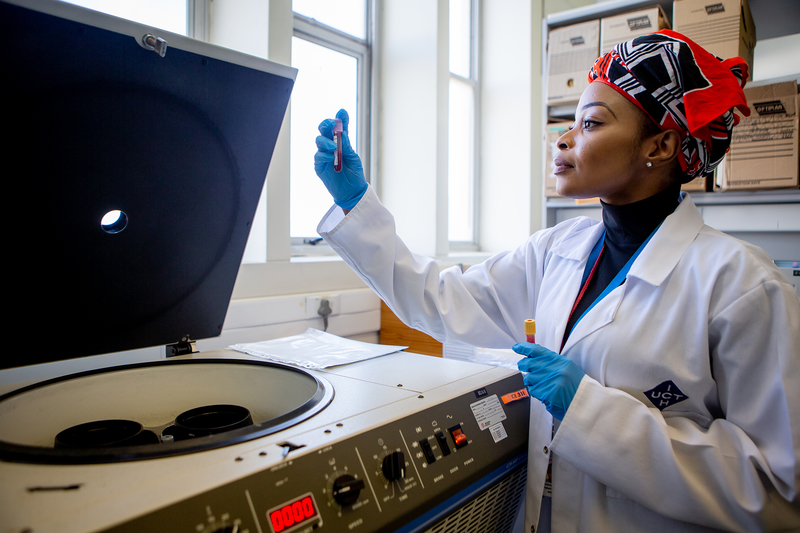

Dr Joseph Raimondo, a UCT senior lecturer and neuroscientist, leads the institute’s basic neuroscience laboratory and convenes its honours programme. He believes that the Neuroscience Institute represents an opportunity to address the issue of transformation in the field.

“The Neuroscience Institute represents an enormous opportunity to improve people’s lives.”

“There is an urgent need for transformation in neuroscience to ensure that researchers and academics reflect the diversity of South Africa, which will help us more easily prioritise and address research problems relevant to our context,” he says.

“The honours program in neuroscience is really the entry point for young South Africans interested in a career in neuroscience research. It’s therefore crucial that we make resources available to encourage and support those from under-represented backgrounds to study neuroscience at UCT.”

A new UCT initiative extended funding support for honours students combined with the Neuroscience Institute making funds available has meant significant financial support for black South African students doing the programme this year.

“It is not enough that the Neuroscience Institute is relevant to today’s challenges in health care in Africa and globally,” concludes Fieggen. “It must also have the capacity to answer tomorrow’s questions.”

This story was published in the fourth issue of Umthombo, a magazine featuring research stories from across the University of Cape Town.

This story was published in the fourth issue of Umthombo, a magazine featuring research stories from across the University of Cape Town. Umthombo is the isiXhosa word for a natural spring of water or fountain. The most notable features of a fountain are its natural occurrence and limitlessness. Umthombo as a name positions the University of Cape Town, and this publication in particular, as a non-depletable well of knowledge.

Read the complete fourth issue online or subscribe and receive new issues in your inbox every few months.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Research & innovation