Lightboard makes teaching effective during pandemic

17 December 2021 | Story Stephen Langtry. Photos Supplied. Read time 7 min.

“I think of online education a bit like an Apollo space mission: I’m awed by its potential to change the world forever, but petrified of the disaster that would unfold if it goes wrong,” said Associate Professor Jimmy Winfield. The accounting scholar of the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) College of Accounting, who won UCT’s Distinguished Teachers Award in 2016, believes that he shared the same sentiments with many lecturers thrust into remote teaching in 2020.

“Personally, I just couldn’t bear the idea of these voiceover PowerPoint presentations,” he added, “because I would have bored myself making them; never mind the poor students that would have had to watch them!” Instead, he sought new ways to make online education more engaging for the roughly 2 000 first-year students that he has taught since then.

“In 2019 I was lucky enough to film two videos on the lightboard at CILT [Centre for Innovation in Learning and Teaching],” Associate Professor Winfield said. “When COVID hit, I had to think about how I was going to teach FR1 [Financial Reporting 1]. I remembered those CILT lightboard videos and the positive student feedback. Of course, I couldn’t get on to campus, let alone access CILT, so the only thing to do was to build my own.”

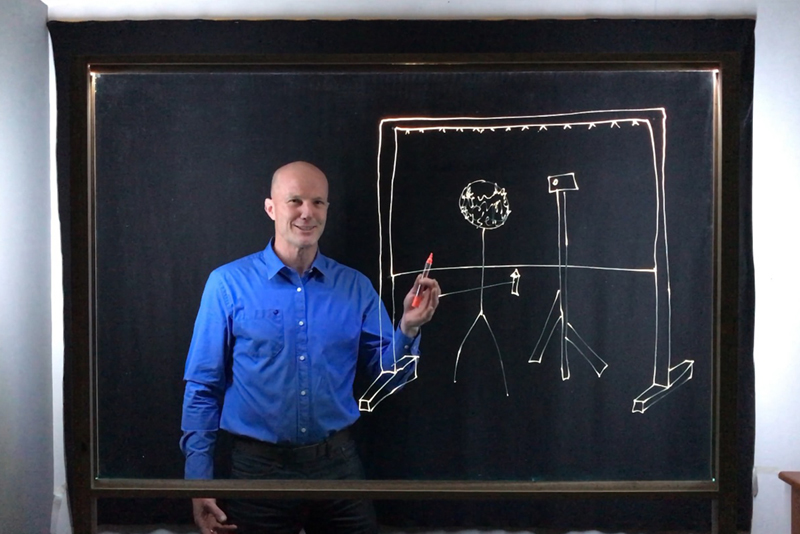

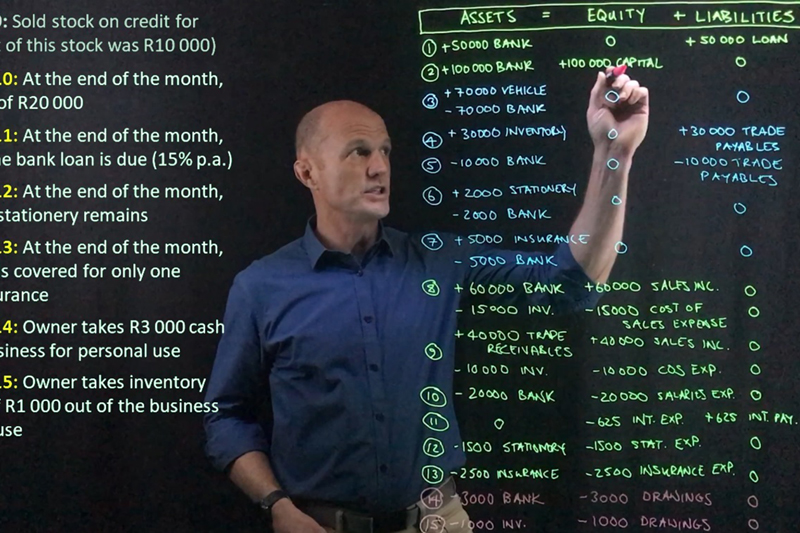

A lightboard is typically a metal-framed structure that looks like a big whiteboard on wheels, except that the “board” is made of glass, and LED lights are recessed into the frame. An instructor stands on one side of the lightboard, writing with neon pens that light up on the glass, while being filmed from the other side. The image is then inverted, so that the writing appears the right way round on the video. This creates a dynamic learning experience, in which the viewer remains engaged as a result of seeing a problem being worked through by hand, along with the instructor’s perpetual ability to make “eye contact” with, and talk directly to, the camera. Winfield made his lightboard using pine and whatever other materials he could source, along with a lot of remote guidance from the folks at CILT.

Building from scratch

“Building it wasn’t easy, but the most time-consuming thing was finding what I needed,” said Winfield. At first, he attempted to build the lightboard using a sheet of Perspex but the first wipe with a cloth left a mess of indelible scratches. He then discovered that, in fact, he needed ultra-clear glass, and was overjoyed when eventually a manufacturer in Paarden Eiland gifted him a piece from stock they had prepared for a new Rolls Royce showroom.

“It is brilliant because it genuinely feels as though we are attending a lecture.”

In his spare room at home, now converted into a makeshift lightboard studio, Winfield has created more than 40 hours of video, spanning 15 academic weeks, which is most of first-year accounting. With the majority of instruction still expected to be online in 2022, he plans to use the lightboard a lot more.

Student feedback has been fantastic. In the most recent course evaluation for FR1, 90% of students strongly agreed that Winfield and his lightboard had made a valuable contribution to their learning, with one student commenting, “I like the use of the board as I can follow along and do the calculations together, as opposed to watching a slideshow being read to me.” Another comment read, “It is brilliant because it genuinely feels as though we are attending a lecture.”

Using the lightboard has involved overcoming many varied challenges. “The learning curve has been just about vertical,” said Winfield. “I’ve gone from knowing nothing about video editing, to confidently using green screens and keyframes. At first, I was uncomfortable spaking to the camera, but now it feels natural, as if my students are right behind the lens.”

After someone complained in the first round of student feedback last year that “the squeaking pen is driving me nuts”, he found a way to special order two packs of ‘silent’ neon lightboard pens from the United States of America (USA). This year, when he ventured into using his lightboard as a live teaching tool, the first attempt did not go well. “The live sessions require three devices and five pieces of software to work perfectly in sync, and that day just about everything failed all at once. [There were] hundreds of eager students on the other end of a Teams call, and there’s me standing alone in the dark. But fortunately, I somehow solved every issue before the next session, and we never looked back from there.”

Building the lightboard cost him about R4 000, though the bigger investment is his time.“Ten minutes of recorded video requires four hours of planning, prepping, shooting, and editing,” he said. “But it’s worth every cent and every second because of what it makes possible in the virtual classroom.”

Distinguished teacher

Winfield’s love for teaching is evident. Besides the UCT Distinguished Teacher Award, he has also received the 2018 CHE-HELTASA National Excellence in Teaching and Learning Award. A UCT graduate, he worked as a school teacher in the USA before returning as a lecturer in 2006.

“If it will help just one student, I’d love to be a part of that, just as others have helped me.”

Winfield gave a presentation on the lightboard at the 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, where it sparked quite a bit of interest. “It would be fantastic to publicise the power of the lightboard. Even if other lecturers don’t go so far as to build one, in 2022 they should just be able to use CILT’s lightboard,” he said. “Please encourage anyone interested to reach out to me – if it will help just one student, I’d love to be a part of that, just as others have helped me.”

In particular, Winfield was quick to thank Stephan Steyn, a videographer at CILT, who gave him valuable technical guidance; Carla Fourie, a senior lecturer from CHED, who took on many other responsibilities for FR1, giving him time to focus on the videos; and Lubabalo Badi, Vula consultant, who, along with the rest of the Vula Help team, provided invaluable assistance.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.