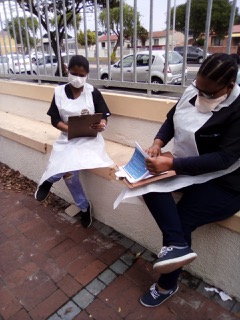

Community rehabilitation workers advocating for disability inclusion during lockdown

10 December 2020 Read time 4 min.(1).jpg)

At the beginning of the national lockdown related to the COVID-19 pandemic, community rehabilitation workers were invited to participate in a four-week writing circle about their experiences of disability inclusion as frontline workers. This was an opportunity to highlight their efforts as well as their invaluable knowledge of community needs.

Since 2012, the Division of Disability Studies has been training students in community-based, disability-inclusive practice, through a one-year accredited qualification at NQF level 5. Some students were community health workers or home-based carers, while others had done a primary health care vocational training qualification. This cadre of health care workers are uniquely placed to offer both factual and social-emotional support to persons with disability and their families in their communities. However, their work and labour often remains invisible and unacknowledged.

At the beginning of lockdown related to the COVID-19 pandemic, alumni were invited to participate in a four-week writing circle about their experiences of disability inclusion as frontline workers. This opportunity highlighted the vital work they do, as critical members of ward-based outreach teams, as well as their invaluable knowledge of community needs. One community rehabilitation worker (CRW) stated, “I worked from my home via Whatsapp, checking on my client to see how she is doing during the lockdown … I was able to encourage her to keep doing the exercises”.

In their weekly reflections, CRWs revealed their precarious positions and personal difficulties. They recognised the importance of hygiene within the content of the pandemic and taking care of one another, since they witnessed many people suffering or dying as a result of insufficient information. They realised that by moving around and being in contact with too many people, they could spread the virus. They also had to address the fear and anxiety of people who they visited at home, while at the same time processing their own fear and anxiety.

Another CRW shared her experience of being tested for COVID-19 while grieving the death of a nursing colleague. She was helped with grief counselling by the Faculty of Health Sciences’ Emeritus Associate Professor Pat Mayers from the Division of Nursing: “The day that I’ll never forget is when I received a call from work early in the morning asking me to rush to work because one of the staff is positive. So, I was very scared; then I rush to work. I found all the staff are queuing outside doing tests, gates are closed for patients… I do the test; it was so painful, especially that stick that has been put inside the nostrils down the throat.”

in community-based and disability-inclusive practice.

Community rehabilitation workers also related daily struggles they were faced with such as the shortage of yeast in the supermarkets during the pandemic, which was needed for making bread for their families, and the need to assist elderly community members with accessing pension.

These health workers recognise that there is still a need to advocate for respect and caring, especially for people with disabilities to be included in their communities. Through living and working in their own communities, they bring incredible local insight and support to the most vulnerable people. Their deep understanding of communal practices and vulnerabilities means that they are able to make a real, sustained difference. Ironically, the CRWs also feel that they are not recognised while they are doing a credible job. The writing circles provided support to the CRWs to see their work made visible, but also for others to see the value and importance of tapping into local knowledge and experiences.

One CRW shared her role in providing information and educating communities. “I am a parent to my children and to the children of my community; they say it takes a village to raise a child. I am that parent who cares about my community children because I don’t want to see any child be affected with COVID-19. One day during the week, I was not at work because there was no site for us to go volunteer. I saw four children playing in my street. So, I called them and educated them about COVID-19... to show how to wash their hands and social distance. I had a few masks that I gave them; they were so happy wearing those masks. I said to them they must protect themselves and ask their parents to make them masks. I gave them a pamphlet that shows how to make a cloth mask. I also distributed pamphlets to the nearest shops, and handed out some to those who were passing. It felt so good to educate my community.”

They also shared the upside of the pandemic. “Doctors, nurses and essential workers are being praised. The important role of teachers is recognised …. The pandemic has given me time to reflect and take care of what is important to each individual - health and hygiene… every day, I strive to look for the positive in challenging situations,” she said.

Article submitted by Theresa Lorenzo, Vuyokazi Lugcalo, Christinah Mabuie, Nomalinde Xelithole and Nontobeko Kamte, Inclusive Practices Africa, and Division of Disability Studies,Department of Health and Rehabilitation Science.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.