‘The symbolism of District Six is absolutely powerful’

11 February 2021 | Story Carla Bernardo. Photos Lerato Maduna. Read time >10 min.

11 February 2021 marks the 55th anniversary of District Six being declared a whites-only area under apartheid’s Group Areas Act. What was once a vibrant melting pot in Cape Town’s inner city was left barren by the apartheid regime.

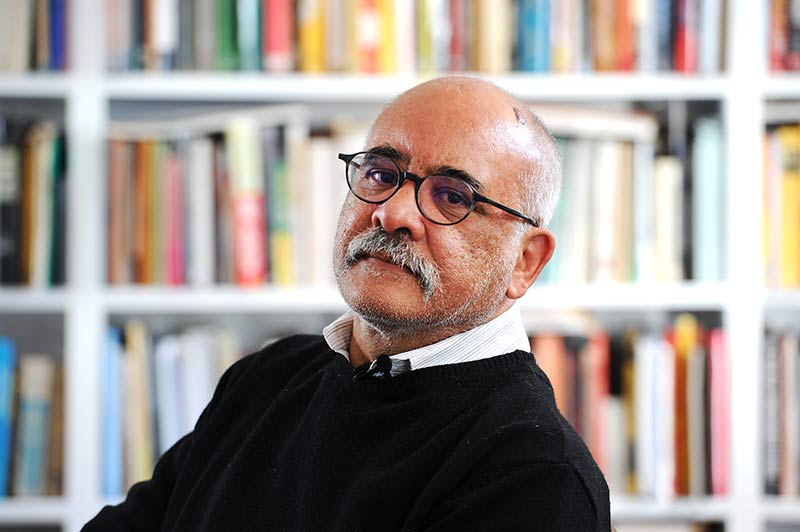

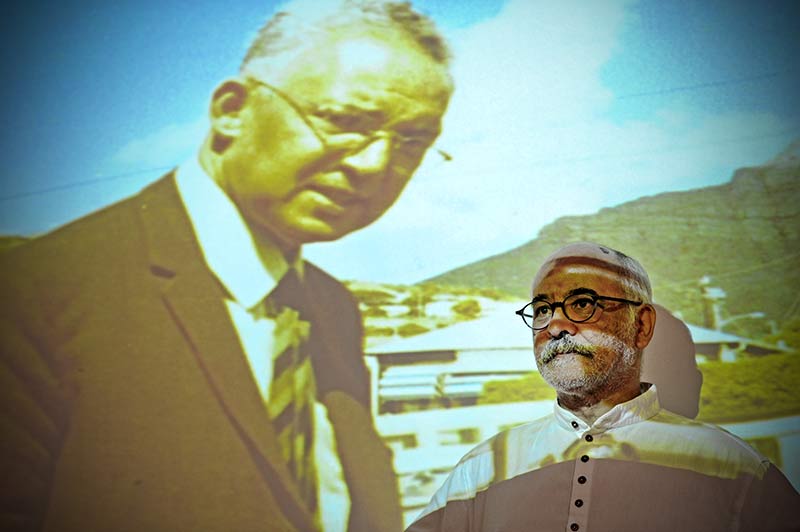

In commemoration of those who were forcibly removed from the area, UCT News spoke to Emeritus Professor Crain Soudien, the chief executive officer of the Human Sciences Research Council and a former deputy vice-chancellor at the University of Cape Town (UCT) who continues to serve in the institution’s School of Education.

Among his expansive publication record are The Struggle for District Six: Past and Present, which he co-authored with UCT’s Associate Professor Shamil Jeppie and the Hands Off District Six Committee, and The Cape Radicals: Intellectual and Political Thought of the New Era Fellowship, 1930s–1960s, which features prominent former residents, such as Cissie Gool and Abdullah Abdurahman.

Professor Soudien also has a strong historical connection to District Six. From 1980 to 1987 he was a teacher at Harold Cressy High School, and in 1998 he became a “Cressy” parent.

Soudien recalls how the Bloemhof Flats were still occupied by District Six residents, and many of their children attended Harold Cressy, during the “dying days of the District”. Some houses remained and, as a teacher, Soudien ran the photographic society and would take students out to document the demolitions.

He has also contributed significantly to political and civic activism in and for the area. Along with Dr Elaine Clarke and Dr Anwah Nagia, he established a string of organisations that operated in the remains of District Six and co-founded the Salt River, Woodstock, Walmer Estate Residents’ Association, which included District Six as its constituency.

Their activism included frequent huisbesoek (house visit) work around Pontac, Chapel and Francis streets, fighting landlords who were evicting families who had been there for generations. This led to important struggles and sometimes victories, such as a win for Francis Street residents who were able to remain in their homes.

They were also successful in their fight with the City Council, who wanted to remove the Trafalgar swimming pool (out of this came the Trafalgar Swimming Club), and in their drive to preserve the Silvertree Creche building and retain the Zonnebloem College. They secured victory against the national government, which wanted to install so-called cabinet ministers of the House of Representatives (‘coloured ministers’) in ministerial homes in the area, and won the fight against private developers coming in to redevelop the area. Their activism also led to the birth of the District Six Museum Foundation, which Soudien established with Clarke and Nagia in 1991.

Carla Bernardo (CB): What were some of the ways the District Six community contributed to South Africa?

Crain Soudien (CS): District Six is central to the cultural, sports, educational, political and social history of Cape Town and South Africa. Some of the oldest sports clubs in the country have their origins there: tennis, soccer and rugby clubs [and] clubs like Young Men’s Own were established in District Six. The first public tennis courts for people of colour were established there.

Politically, the area was immensely influential. All of the city’s major political resistance organisations can trace their history back to District Six, beginning with organisations such as the African People’s Organisation (1901), led by legendary Capetonians such as Abdullah Abdurahman; the Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (1915), led by Clements Kadalie; and then the Non-European Unity Movement (1944), led by extraordinary Cape Town intellectuals Goolam Gool, Isaac Tabata and Ben Kies. Extraordinary too is the fact that the South West African People’s Organisation had its roots – before its formal establishment in 1960 in Windhoek – in District Six. Its founder, Toivo ya Toivo, had worked in Cape Town in the 1950s.

Out of District Six came cultural societies such as the Eoan Group, which performed La traviata in South Africa for the first time in the 1930s. Trafalgar High School and Harold Cressy High School, now somewhat dimmed in lustre, are legendary. Harold Cressy in its prime was one of the country’s most powerful schools. Despite its material deficiencies, its teachers were intellectuals groomed in the informal studios of District Six. They were denied the opportunity to share their talents with the greater Cape Town and South Africa by the apartheid experience. They were not recognised by UCT and instead established their own progressive educational movement outside of it in the form of the New Era Fellowship, which was established at the Stakesby-Lewis Hostel in 1939.

CB: Why did the apartheid government target District Six?

CS: It is not only District Six that was targeted; the whole of the country had to deal with the removals. Every town and city has its traumatic story to tell about people being removed. District Six is the most visible because it was prime land in the heart of a city and because it was so iconic in the country’s history as a place of refuge and community for so many South Africans of all backgrounds.

It was the place to which many immigrants into the city first came and found help and support. These immigrants include people like Clements Kadalie, who came from Nyasaland; many white working-class British families; many, many families who can trace their roots to the four corners of the globe – the Caribbean, the Philippines, the Asian subcontinent, the Ottoman Empire; and then desperate people fleeing from the pogroms in places like Lithuania. District Six was a veritable melting pot. It would have been home during the ’20s and ’30s to, literally, the people of the world.

Its history constituted a challenge to the official story being refined by the colonial government and then the apartheid government that people ‘naturally’ were distinct, separate and could be divided into ‘races’, and wanted to live lives of apartheid separateness. It is this that in the end, many of us will argue, offended the apartheid government most.

CB: And why did they not build up the area?

CS: The place was not built up because the area was declared “salted earth” by the people. It was made such a moral symbol of injustice that not even the kragdadigheid (brutality) of the apartheid government at the peak of its power could simply go in there and rebuild the area. The symbolism of District Six is absolutely powerful. Its power is the challenge it poses to formal authority. That challenge remains to this day. Nobody can go in there and simply develop the area. The people of Cape Town have a grip on the area which is hard to describe. It is an unwritten but almost biblical authority – the authority of the people.

CB: Where were the so-called race groups moved to?

CS: The removals were part of the apartheid spatial planning processes that were set in motion after the 1960s. But before that the colonial authorities had already begun moving African people – blaming them for the bubonic plague in 1901 – and moving them, successively, to the Breakwater Prison (which, very interestingly, is now the campus for UCT’s Graduate School of Business), Ndabeni and then to Langa in 1927. But people classified as African continued to live in District Six and many, in the nature of District Six, assimilated into the wonderful community and simply became District Sixers, until the Group Areas Act and the Population Registration Act of the 1950s forced them to be classified in racial terms.

How people classified and were classified in District Six is an enormously important story that has yet to be told in its full and dense complexity. The horror of it is that people had to – some of them, let it be acknowledged, wanted to – take on racial identities that meant much less to them than they would later become. The ‘coloured’ identity, for example, grows out of the experience of segregation and racialisation. It was there, it came in the late 1800s, but it was deepened and made into a thing over a period of about 50 years. The townships which were established in Cape Town, such as Manenberg, Bonteheuwel, Heideveld and many others, came to assume separate racial identities because of legal imposition.

CB: At a broader level, what was the impact of the removals?

CS: The impact of the removals has yet to be fully described and accounted for. Dumping people in pitifully poorly resourced areas, far away from people’s opportunities for and places of work, produced throughout the country the experience of the South African township. This experience is largely responsible for very many of the deep social challenges we have to confront today and, most traumatically, that of criminality and antisocial behaviour.

People were forced into making lives for themselves in inventive and creative ways. Many of these continued to be life-sustaining and generative, such as the continuance and reproduction of the support structures that would have existed in District Six, their religious organisations, their cultural clubs, sports organisations and so on. But many practices that had existed in District Six, such as gang cultures, became dark and impenetrable alternative power networks which thrived on the material poverty of the people.

CB: And how do you think the removals affected and continue to affect former residents, families and, perhaps, their descendants?

CS: Yes, the trauma is passed on, in ways that are still to be understood, from generation to generation. These ways are evident in the continued suspicion of institutions of authority, such as the police, the courts and even institutions such as schools. Social mobility is enormously difficult in communities such as these. It is not just the shortage of examples of people who have broken out of the cycles of disadvantage that are reproduced in the townships, it is the cultivation of alternative normative orders which have short-term gratification as their animating impulses.

‘Living in the moment’ is a consciousness which is enormously difficult to counter. It weakens the capacity of people towards self-control and concern for others. It is, in the end, another form of ugly and predatory capitalism. There are not enough strong and positive social traditions to help people take a larger and longer-term view of their lives. Religious organisations are enormously important as counterweights to this culture of immediacy, except, of course, when they themselves become sites of instant gratification.

CB: Finally, does District Six continue to hold importance in South Africa? And what can we still learn from its past, present and potentially, future?

CS: People such as myself who are involved in the narrative of District Six are not happy about the exceptionalising of the story of District Six. We do not wish to see the story of District Six given precedence, priority and favour over the experiences of any other community in South Africa. The full picture of what happened during the forced removals needs to be told and available to all South Africans. The trauma of never-heard-of communities in the little towns of the Karoo or Limpopo’s rural Edens needs to be known by all.

This is crucial for understanding what it is to be a nation. We need to take and embrace all our people’s hurts. We need to know how they survived and, more particularly, how they were able to hold onto their dignity and to give their children a sense of possibility for themselves where none seemed available. We know a lot about District Six, but we now need to hear too about every other village, town and city.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.