Woody plants on the march

17 August 2018 | Story Zander venter. Read time 8 min.

Forests are being cleared by humans at an alarming rate. Since 2000, roughly 20% of Africa’s forests have been wiped out. This deforestation has serious consequences, among them a loss of biodiversity and the potential to remove carbon dioxide (CO₂), a greenhouse gas, from the atmosphere.

But trees and shrubs, collectively known as woody plants, appear to be fighting back on another front. Many of these species are gradually encroaching into grasslands and savannas across Africa, particularly in places like Cameroon and the Central African Republic.

We found that woody plants’ cover has increased in large swathes of the continent in the past three decades.

Taken at face value, this may seem to be good news. Woody plants mean more fuel wood for rural communities and increased food for browsing livestock like goats. It may offset the loss in carbon sequestration caused by deforestation.

But more woody plants also means less habitat for grass and other herbs that make grasslands and savannas such productive systems. And that’s a direct threat to the productivity of cattle and certain wild herbivores which rely on grass for sustenance. This is significant because in 2016, Africa produced 6.3 million tonnes of beef – more than double the meat production from sheep and goats combined. Woody plants can also take up precious water resources.

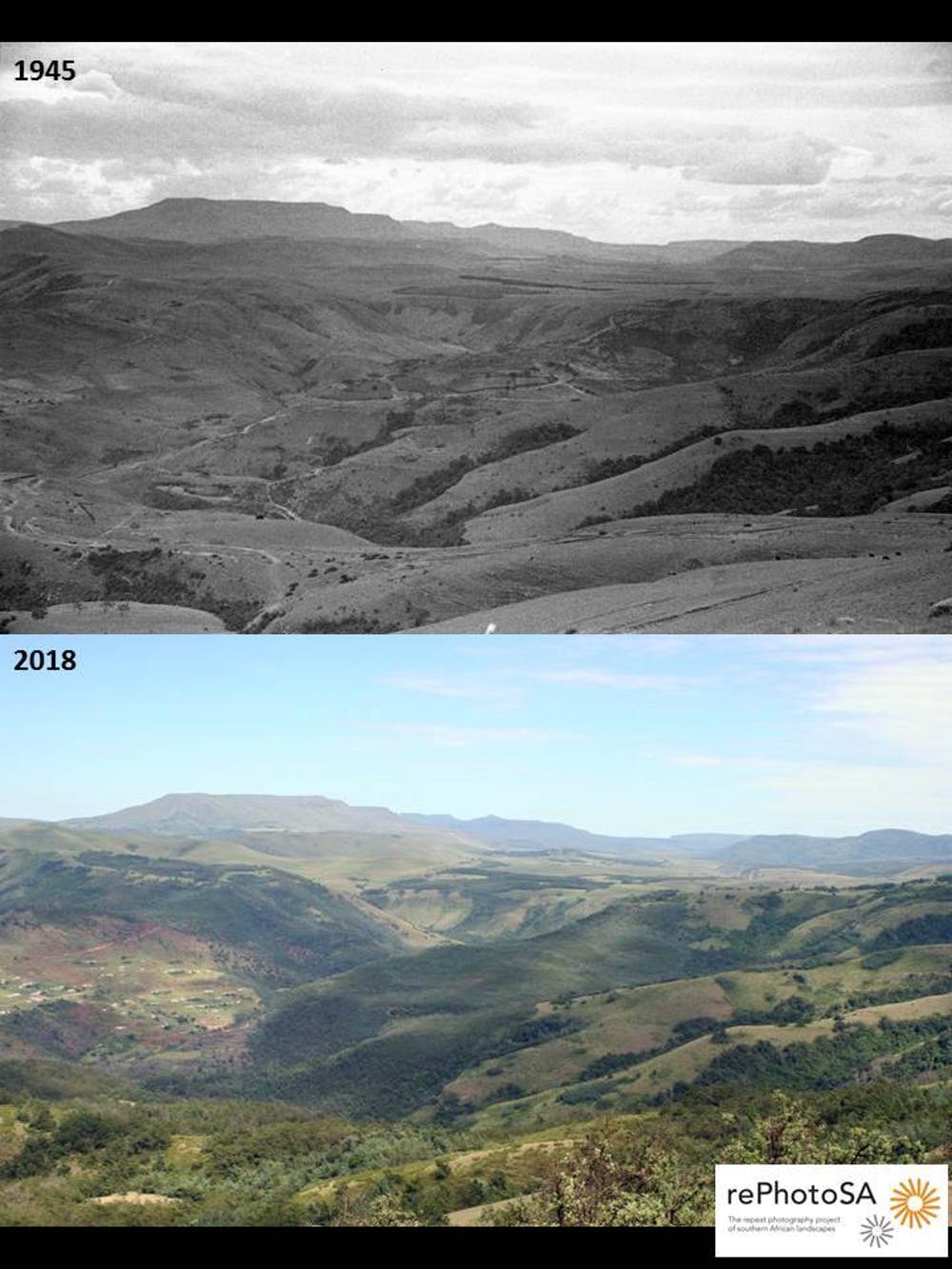

Until recently, scientists relied on historical photographs from land and aeroplanes to investigate changes in vegetation cover over decades and even centuries. This only gives information at a few locations, but these valuable studies have consistently shown that woody plants are expanding their range over parts of Africa.

We set out to expand on this research by exploring change in woody plant cover outside of forests for the entire sub-Saharan Africa region using satellite imagery going back to 1986.

We found that woody plants’ cover has increased in large swathes of the continent in the past three decades. Our findings also suggest why this may have happened: because wildfires have decreased and there are more grazing animals rather than those that just browse. This combination, along with increases in rainfall, temperature and CO₂ emissions, has driven the march of woody plants in the region.

On the march

1945 and 2018. Images courtesy of rePhotoSA. John Acocks (1945) and Zander Venter (2018).

In our research, published in Nature Communications, we found that over the past three decades the cover of woody plants increased in more than half (55%) of all non-forested areas.

Much less of the land (16%) actually lost tree and shrub cover, leaving only 29% relatively unchanged. Some of the countries experiencing the greatest increases in woody plant cover were Cameroon and the Central African Republic. Others, like Congo and Madagascar, underwent a net loss of woody plants.

The cause of tree cover loss is generally well understood: it’s dominated by human-induced clearing for agriculture, timber and fuelwood. But it’s less simple to understand what’s caused the gradual increase in woody plant cover we and others have recorded. The answer may lie with atmospheric CO₂.

Atmospheric CO₂, a by-product of burning fossil fuels but also a key ingredient for plant photosynthesis, has been on the rise since the industrial revolution around 1800. Scientists have suggested that this is causing the increase in woody plants because some experiments have shown that trees benefit more from elevated CO₂ than grasses do.

African experiments with elevated CO₂ have been conducted in greenhouses and plant growth chambers, where factors that limit plant growth in grasslands (like herbivores, fires, limited soil nutrients and water) are absent. And early botanical records, which aren’t online, report that “thornveld” (woody savannas) expanded during the early 1900s, when CO₂ levels were still relatively low. This highlights the complexity of natural systems and the dangers of attributing change to any one factor.

In our study we found that fire and herbivores are possibly as important as climate or CO₂ emissions in shaping Africa’s savannas. Over the past few decades, as human populations have grown, we have reduced the spread and intensity of fires and replaced browsing animals like elephants, kudu and goats with grazers like cattle. This has allowed woody plants to proliferate.

What can be done

Managers and conservationists who wish to mitigate woody plant encroachment can consider diversifying their livestock or wildlife.

...woody plants also means less habitat for grass and other herbs that make grasslands and savannas such productive systems. And that’s a direct threat to the productivity of cattle and certain wild herbivores which rely on grass for sustenance.

Although reintroducing elephants and their ilk might be beyond the bounds of practicality for most livestock farmers, some goats or wild browsers like kudu will go a long way to helping. Some African countries have always had a market for goats and other countries have recently opened up those markets and so now would be a good time to farm with goats.

Targeted and prescribed burning practices could also help keep woody plants under control.

Technology can also be enormously helpful. Since 2017, hundreds of earth observation satellites, including the toaster-sized ones launched by satellite company Planet, have given us the ability to monitor every point on the planet every day. This could be harnessed to monitor how woody plant cover responds to management interventions, to see what works or doesn’t, and where. This information should be made readily available to scientists, governments and land managers to inform future interventions.

To explore other changes in woody plant coverage, visit this interactive map.

Zander Venter is a PhD candidate in agroecology at UCT.