The impact of children starting ARVs late

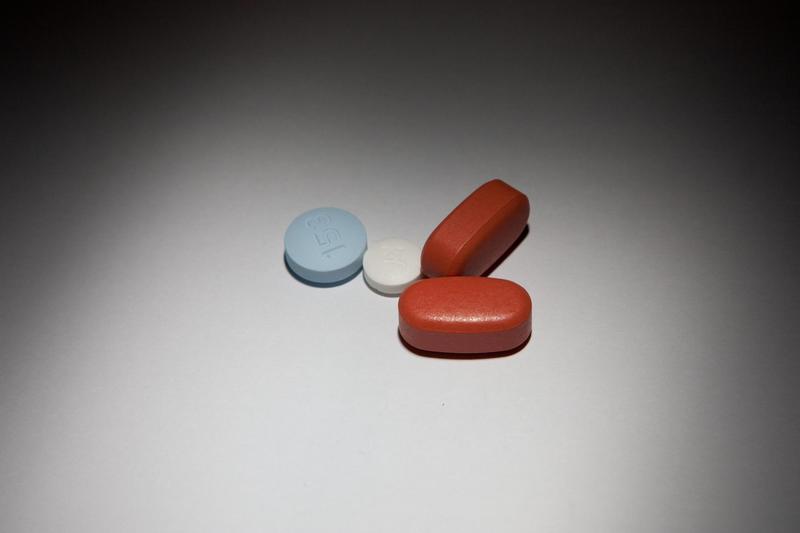

27 July 2018 | Story Mary-Ann Davies and Amy Slogrove. Photo Rico Gustav Flickr. Read time 7 min.

South Africa’s programme to give mothers antiretroviral treatment preventing them from transmitting HIV to their babies during pregnancy and breastfeeding is rightly lauded for saving lives. The introduction of ARVs just after the turn of the century resulted in a dramatic drop in the number of children being born with HIV. In South Africa, the proportion of babies infected with HIV nearly 20-fold from an estimated 19% in 2004 to about 1% in 2016.

This is obviously good news and has been rightly celebrated. But what’s often lost in the narrative is what happened to the children who were infected with HIV before and during the early years of the ARV roll out.

They are mostly children born in the early 2000s.

To understand the longer term effects of ARV treatment during early childhood we conducted research on children aged between 10 and 15. The study involved using historical data dating back 32 years as well as research in five regions of the world. These included sub-Saharan Africa, North America, South America, the Caribbean, South and Southeast Asia and Europe.

Our study compared these adolescents with their counterparts in wealthy countries who were also on ARVs. We looked at how the treatment they’d received as children had affected them later in their young lives. Almost all children in our study were on antiretrovirals by the time they were 10. But the children from developing countries started treatment later than their developed country peers.

"We found that children in developing countries were substantially disadvantaged compared with their counterparts in developed countries."

We found that children in developing countries were substantially disadvantaged compared with their counterparts in developed countries. The big discrepancies we uncovered were that children in this cohort had much higher fatality rates during adolescence, they suffered from stunting and their development was stymied.

Our study is the first global comparison of adolescents that acquired HIV as newborns. It highlights the challenges around treatment for this group of children and should inform policy responses needed to service them.

Our study echoes compelling evidence over the years that shows the benefits of children starting treatment as early as possible. It substantially reduces their chances of dying as well as their patterns of illness and it improves their growth. The higher death and poor growth of this generation of adolescents in countries like South Africa is most likely the legacy of their poor access to treatment as children.

Stark differences

We combined data from research groups studying adolescents with perinatal HIV infection. There were about 38 000 HIV positive adolescents in our study. Close to 80% of the adolescents were from sub-Saharan Africa and about 65% lived in low-income settings.

We found that, in most cases, adolescents from high income countries, particularly North America and Europe, started treatment between the ages of 1 and 2.

Children from low and middle-income countries like South Africa were only likely to have started treatment between the age of six and eight. They became infected because their mothers either had limited or no access to ARVs. As babies, they too would have faced restricted access, often being put on ARVs only after they’d become seriously ill.

There were two main differences between these two groups.

The first major difference was that adolescents in low and middle-income countries were about three times more likely to die between the age of 10 and 15 compared to those in wealthy countries. In high-income countries about one in 100 adolescents died in this period compared to about three per 100 in low-income countries.

"The true difference could be even greater because adolescents in low and middle-income countries were more likely to be lost from care, and may have died without the researchers knowing."

The second big difference was in growth rates. Growth is a key indicator of how healthy a child is. Children in both developed and developing countries showed poor growth compared with national averages. But the children in high-income countries were able to catch up and, in most instances, they nearly reached the heights of their uninfected peers. For their part, children from poorer countries remained significantly short for their age.

So what next?

As access to antiretroviral therapy increases across the globe, children who acquired HIV at the time of their birth or through breastfeeding are living longer. In the early 2000s this was unimaginable.

![]() This population of adolescents is likely to decline due to the declining numbers of new HIV infections in babies. But the global health community owes it to the current generation of adolescents to ensure that they have proper access to treatment and support as they become adults. And there is a lot more work to be done so that future generations are born and stay AIDS free.

This population of adolescents is likely to decline due to the declining numbers of new HIV infections in babies. But the global health community owes it to the current generation of adolescents to ensure that they have proper access to treatment and support as they become adults. And there is a lot more work to be done so that future generations are born and stay AIDS free.

Mary-Ann Davies is an associate professor and director of the Centre for Infectious Diseases Epidemiology and Research at UCT. Amy Slogrove is a senior lecturer at Stellenbosch University.