New coal power will cost SA billions

11 June 2018 | Story Kate-Lyn Moore. Photo Pixabay. Read time 8 min.

South Africa does not need any new coal-burning power plants, asserts a recent study from UCT’s Energy Research Centre (ERC).

Aside from being emissions intensive, newly built coal power plants would add billions to South Africa’s power bill over the course of their lifetime, and would force cheaper and cleaner renewable-energy alternatives out of the system for years to come.

The ERC, which has a multidisciplinary bent, focuses on a wide variety of energy topics.

“Our group, in particular, looks at the relationship between energy systems, development pathways and the economy,” commented Jesse Burton, who co-authored the report with fellow researcher Gregory Ireland.

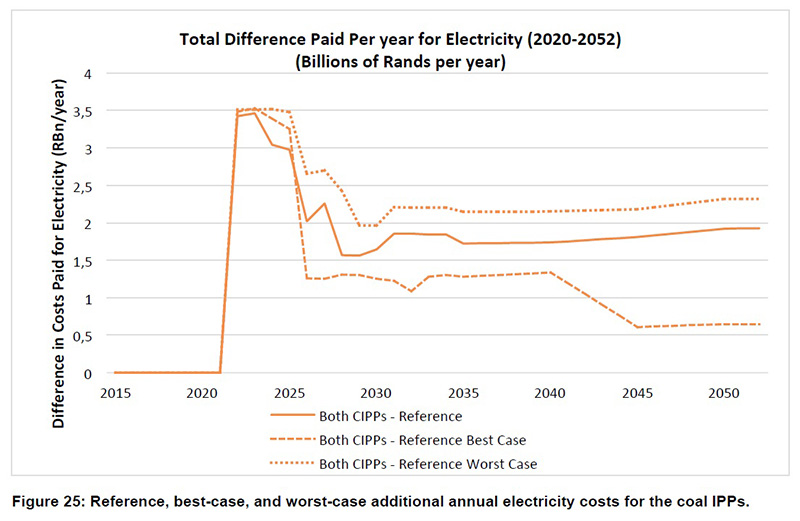

The study focused on two planned independent power producer (IPP) coal plants, Thabametsi and Khanyisa, and determined that the plants will cost the country an additional R19.68 billion in present value terms over their lifetimes, compared to an optimal and least-cost energy system that combines wind, solar and gas.

Thabametsi and Khanyisa are the preferred bidders within the first bid window of the coal-baseload IPP procurement programme, and are required to begin operating by December 2021.

The two coal plants were forced into South Africa’s Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) of 2010 – a document that is still in effect, despite being, in the words of Burton, “irrelevant and outdated”.

Then and now

The world has changed significantly since the IRP was gazetted in 2011, with renewable energy prices having decreased by up to 90%.

“It’s a completely different ball game. And we actually know how much these two coal plants are going to cost, because they had to bid into a process … So you can see that even current renewables are already 40% cheaper than these two new coal plants.”

“We know for a fact, no matter how you roll the dice for this, it is going to cost us more. It’s going to have extra, unnecessary emissions, and we need to take that into account.”

“But given the IRP of 2010, the minister is still pushing ahead with these two plants.”

“We know for a fact, no matter how you roll the dice for this, it is going to cost us more. It’s going to have extra, unnecessary emissions, and we need to take that into account,” added Ireland.

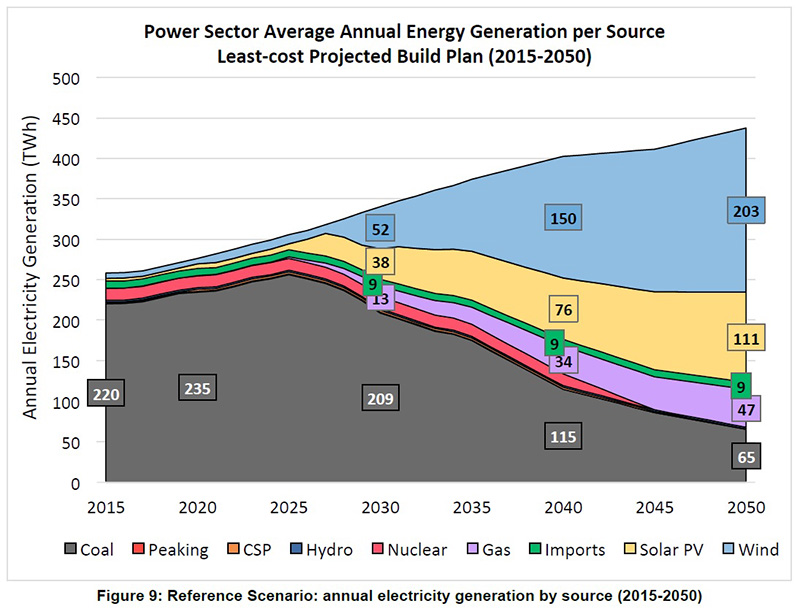

The ERC report is based on modelling that seeks to map out a least-cost energy system.

“What these models do is build you an energy system that is the lowest-cost one, subject to various constraints … All of them say we don’t need new coal, we don’t need new nuclear. That is actually one of our key findings, again, that supports the other independent analysis that exists,” said Burton.

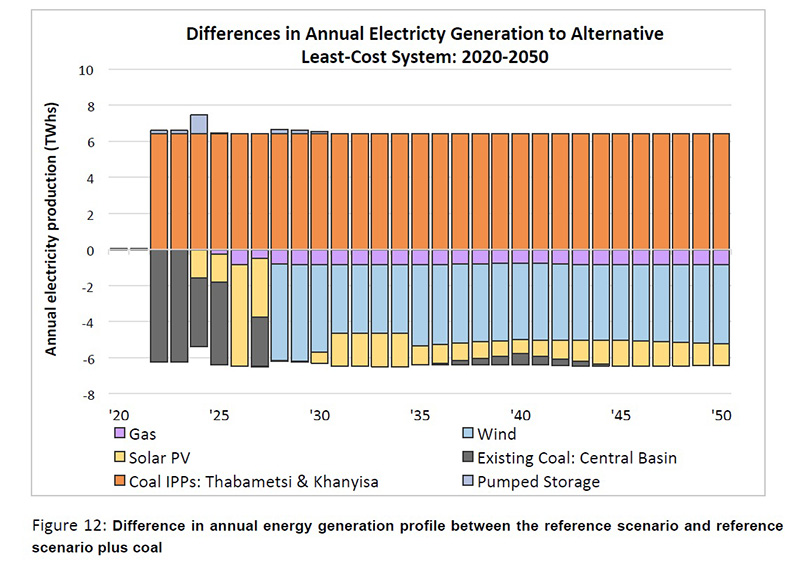

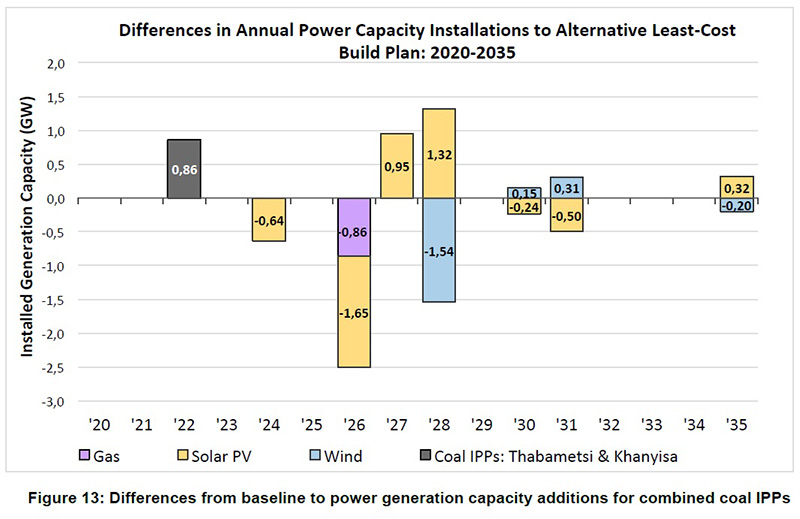

“What you can do is force those plants into your model, and you can directly see what the difference is. You can see all of the deviation from your optimal plan,” explained Ireland.

These models take various constraints into account, such as the need for an energy system that can deliver the same amount of service.

“It builds in a whole suite of technologies, and runs the whole system in a way that is considered optimal, based on other constraints as well, such as greenhouse gas limits, etc,” said Ireland.

Consistent with other modelling work done in the country, a least-cost system would comprise an energy mix of wind and solar, with gas included as back-up capacity.

“The cheapest energy system we can possibly build going into the future is going to be almost all new renewables.”

“It is better in almost every way … It is not impossible; people are doing it everywhere. It is not a science fiction fantasy anymore.

“This is good news; it is not enough as well. Yes, the cheapest energy system we can possibly build going into the future is going to be almost all new renewables … There is no such thing as cheap fossil fuels anymore,” he said.

“Of course, if you ever really costed water, health, air pollution … they were never cheap,” Burton added.

Expensive and dirty

The cost implications revealed in the study are startling, but in reality things could be far worse.

“We have tried to be very conservative with our consumptions here. We are modelling the future. So our ‘worst case’ is more like a realistic scenario. It could be much worse than this,” said Ireland.

The same can be said of the plants’ additional emissions. At the time the current IRP was gazetted, the two IPPs were declared to be ‘clean coal’ – with lower carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions than a number of Eskom’s other plants.

But a landmark court case that questioned the environmental impact of the Thabametsi power plant resulted in a judge ordering a climate-change impact assessment for the station.

“Are we building an energy system for the 19th century, or are we building an energy system for the 21st century?”

The assessment revealed the presence of other, more potent greenhouse gases in the mix, including nitrous oxide (N2O), which is roughly 300 times more powerful per unit of volume then CO2.

In the team’s reference scenario, the two plants contributed an additional 200 million tonnes of emissions during their lifetime.

“It is all additional, and almost totally offsets some really big policy interventions that the government is putting in place to deal with climate change,” explained Burton.

“You end up back where you started. But you’ve paid for it. You’ve paid to go nowhere,” she concluded.

Energy surplus

The study has shown that the planned IPPs are not necessary. Where the IRP of 2010 expected electricity demand to grow rapidly, demand has remained more or less constant over the past 10 years. In fact, the country already has surplus electricity, Ireland pointed out.

These two plants are supposed to be signed into operation for 30 years, with a fixed power purchase agreement in place. This would mean that Eskom would be forced to purchase a set amount of power from the IPPs, instead of selling power from its already underutilised fleet.

Such a scenario would be disastrous for the company, which is already in dire financial straits. It also means that South Africa’s already costly electricity would increase in price.

Moving forward

“We’ve already had a lot of good feedback from people. We’ve been contacted by a lot of financial houses who are interested in understanding this, interested in understanding their role in financing unnecessary infrastructure. I think a lot of people in civil society are going to use the study for advocacy, to make their cases stronger,” said Burton.

“What people are trying to say is: ‘You shouldn’t be forcing these decisions into the model when they haven’t reached financial close yet, and the impacts are really big. If this is our policy choice, what are the cost implications of that? Are these trade-offs worth making?’

“There should be a lot more clarity around these technology choices, what the emissions are and how they relate to the development pathway that the country is aiming towards. Are we building an energy system for the 19th century, or are we building an energy system for the 21st century?”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.