Sky's no limit for Habarulema

18 April 2017 | Story by Yusuf Omar. Photos Robyn Walker. Video Saadiq Behardien.

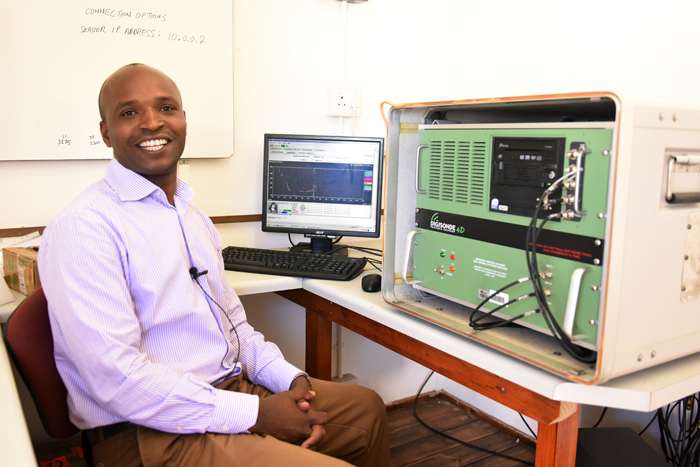

In between mapping out the ionosphere and negotiating with wary gatekeepers to get “classified data” from GPS receivers, Dr John Bosco Habarulema has a bigger, and possibly more daunting, mission.

But more on that later.

Habarulema, a UCT alumnus*, works some pretty cool machines at the South African National Space Agency (SANSA) in Hermanus. He’ll be caught doing anything from investigating the effects of solar storms to keeping an eye on the South African ionosonde network all the while appreciating Hermanus’s clean environment “because there’s no train station here”.

Still in his 30s, Habarulema is already one of the biggest names in space science on the continent and a world leader in ionosphere research.

In December 2016 he won the 2016 Africa Award for Research Excellence in Space Science at the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting Honors Ceremony. This followed his 2014 Sunanda and Santimay Basu Early Career Award, which is presented by the Space Physics and Aeronomy section of the American Geophysical Union to young scientists who have already made “outstanding contributions to research in Sun-Earth Systems Science”. He was the first African to receive the Sunanda Award.

Space science is critical to just about everything on earth, even if things like weather forecasting and mobile phones have become so normal that the satellites they depend on are out of sight and mind, he says.

More space scientists, please

Africans have been at the leading edge of studying the stars for millennia, as UCT alumnus Thebe Medupe argued in 2014. Now, Habarulema wants to overcome unpredictable infrastructure (“sometimes I have to literally fly and drive to fetch data and bring it here”) and improve opportunities for young scholars in order to set space science on the continent to hyperdrive.

“If you go outside South Africa and Nigeria, [space science and technology] are not really well developed. I thought I could contribute in developing some of those areas,” he says.

As a trained teacher – he studied maths and physics with education at undergraduate level after his A levels – Habarulema is determined to be a role model and mentor for budding scientists.

During his schooling years in Uganda, nobody in his village had a formal education. Walking 14 kilometres to and from school every day meant that by the time he reached high school, he had to look within for motivation.

“There was nobody to look [up to],” he remembers.

One of his core missions, then, is to grow space science on the continent. He supervises students from Ethiopia, Rwanda, Uganda, Kenya and Nigeria, plus some students at Rhodes and UCT. He has worked with students from Ghana and Ivory Coast as well.

“It’s all over the continent,” he says.

They are all working on projects that call for either new observations or for developing models based on new hypotheses.

What he writes about

Habarulema himself is mapping the ionosphere – the layer of Earth’s atmosphere that is rich in ions and electrons and can reflect radio waves – above the entire African continent.

To skin a complex story to its bones, he uses GPS satellites at the civilian frequencies to map the continent’s ionosphere on a regional basis. It’s a project he started during his PhD, when he used anomalies in how long it took GPS signals to pierce the electron-dense ionosphere to map southern Africa.

“The time delay experienced by the signal is directly proportional to the integrated electron content along the line of sight and inversely proportional to the frequency of propagation,” says Habarulema.

This gives an idea of electron density distribution at different locations.

“That mapping contributes towards understanding space applications such as positioning, navigation and communication, to name but a few,” he explains.

There’s no reason it can’t be done across the world, too, and a number of people are working on these aspects.

Unexpected hurdles

Well, in theory.

Data from GPS receivers is sometimes guarded a bit too fiercely by the people who host receivers.

“Everybody thinks that the GPS receiver is for military applications,” he sighs, “so they say it’s classified information.”

The lack of sensitisation and knowledge of space science basics is a major hindrance, he says. On a more general level than his own research, many countries lack the money to buy the necessary equipment and, because they do not have structured space science programs, acquiring this infrastructure is not a priority. In the long term, this should change on a continental level so that Africans are in charge of their own space without relying on outsiders, says Habarulema. With the African Space Policy and Strategy in place, space-based activities will be consolidated over the African continent.

“I’m trying to fill all those voids by not using instruments that are on the ground, but using instruments that are flying.”

But tailoring data from satellites to answer his research questions takes time. Lots of time. The data is typically designed for other things – but for now, needs must.

The big goal

“It’s an ongoing project,” he says.

As far as his mapping work is concerned, the end goal is to have the ever-changing ionosphere map visible in real time.

“Once you use it in real time, you can always see how space is changing in different places,” he says.

Navigation, communication, surveying and the defence applications could all benefit.

As important as his research is, Habarulema is uneasy about placing himself at the centre of his goals. He’s unequivocal when asked what his “big goal” is.

“If someone asks me what makes you tick … I don’t look at myself as a person. Because if you talk about doing something for myself, from my background, I would believe I have succeeded.”

Egocentrically, then, he’s satisfied.

“But what I want to see is to see the people who also don’t have the opportunities making it in life. That’s my big goal. It’s essentially to train and bring others up. I don’t know whether that is achievable in totality, whether everybody can come up, but if I can contribute a small bit, that makes me happy.”

When people ask what he’s proud of, he doesn’t point to his scientific publications. Those he’ll write without fuss.

“When I see a student graduate, that’s my biggest satisfaction, because training a student and graduating a student is not actually that person alone,” says Habarulema. “You’re helping an entire generation. You’re helping a family; you’re helping a community. So that’s my biggest aspiration.”

Watch the video:

Meet space scientist UCT alumnus Dr John Bosco Habarulema.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.