South Africans learn that the law can be a double-edged sword

02 November 2016 | Story Penelope Andrews

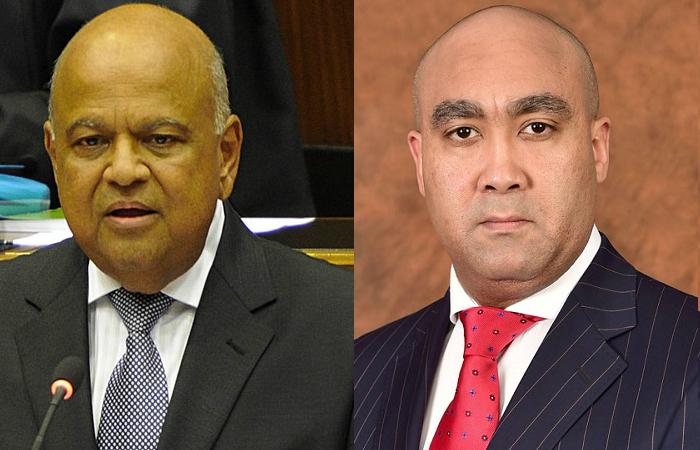

South Africa’s National Prosecuting Authority charged the country’s finance minister Pravin Gordhan and two of his former colleagues at the tax authority, Ivan Pillay and Oupa Magashule, with fraud last month. The charge was widely criticised as baseless and politically motivated, amid allegations of state capture. It sent the currency into a nosedive and wiped billions off the stock market. This week, the NPA withdrew the charges on the eve of the trio’s court appearance. The Conversation Africa's politics and society editor, Thabo Leshilo, asked law professor Penelope Andrews for her view.

The significance lies in three things: first, it was the extraordinary level of public attention that the case generated. The airwaves, the media and social media were alight with commentary on the case.

Second was the educational function that the charges provided. Ordinary citizens got another peek at the National Prosecuting Authority and its operations and there is now greater awareness of the meaning of fraud since this was the charge laid.

The third was that as events unfolded they showed that public campaigning and public pressure may actually yield results.

At the moment there is a lot of speculation, some of it quite persuasive. But something as serious as this – a minister being charged and the flagrant disregard for its consequences – requires a concerted probe into the reasons for the actions of the National Prosecuting Authority. We have to move from widespread speculation to confirmed facts.

My sense is that the National Prosecuting Authority was taken by surprise at the level of public disapproval of its actions and the overwhelming support for Gordhan. In particular, they must have been alarmed by the level of legal opinion about the spurious nature of the charges and opposition to the case itself.

The lateness of the decision to prosecute may have been hubris on the part of the head of the National Prosecuting Authority, Shaun Abrahams. Or it may have been a decision of his to persevere and let the chips fall as they did. The decision not to prosecute may also have been a last ditch attempt on his part to save his reputation, such as it was, and to prevent a drubbing by the court.

It actually says contradictory things about the rule of law. It can be used as a shield that protects those who might be falsely accused. This was clearly the case here. But the rule of law could also be a sword –- to attack those who obstruct the nefarious plans of powerful people.

I take no position on whether Abrahams should resign. Many prosecutors make decisions to withdraw charges for a host of reasons, some of them quite legitimate. The better route would be an inquiry into what went into the decision to charge the minister and the two others in the first place. Was it malice? Incompetence? A conspiracy?

An inquiry would highlight whether Abrahams and his team are fit to run the nation’s prosecuting authority.

An inquiry, not necessarily judicial, but led by credible individuals trained in the law, needs to be held into the fiasco. It should be underpinned by a transparent process with unlimited access to a wide range of sources. Only such a concerted effort to clarify what has transpired will ensure that it is not repeated.

Penelope Andrews, Dean of Law and Professor, University of Cape Town. Images by GCIS, via Flickr.

What’s the significance of the charges being withdrawn against Gordhan?

The significance lies in three things: first, it was the extraordinary level of public attention that the case generated. The airwaves, the media and social media were alight with commentary on the case.

Second was the educational function that the charges provided. Ordinary citizens got another peek at the National Prosecuting Authority and its operations and there is now greater awareness of the meaning of fraud since this was the charge laid.

The third was that as events unfolded they showed that public campaigning and public pressure may actually yield results.

What does all this say about the NPA and its independence?

At the moment there is a lot of speculation, some of it quite persuasive. But something as serious as this – a minister being charged and the flagrant disregard for its consequences – requires a concerted probe into the reasons for the actions of the National Prosecuting Authority. We have to move from widespread speculation to confirmed facts.

What’s to be read into the lateness of the decision not to prosecute, coming as it did on the even of their court appearance?

My sense is that the National Prosecuting Authority was taken by surprise at the level of public disapproval of its actions and the overwhelming support for Gordhan. In particular, they must have been alarmed by the level of legal opinion about the spurious nature of the charges and opposition to the case itself.

The lateness of the decision to prosecute may have been hubris on the part of the head of the National Prosecuting Authority, Shaun Abrahams. Or it may have been a decision of his to persevere and let the chips fall as they did. The decision not to prosecute may also have been a last ditch attempt on his part to save his reputation, such as it was, and to prevent a drubbing by the court.

There has always been suspicion there was no case against the the trio and that the charges were politically motivated. This appears to be vindicated by the withdrawal. What does it say about the rule of law in South Africa?

It actually says contradictory things about the rule of law. It can be used as a shield that protects those who might be falsely accused. This was clearly the case here. But the rule of law could also be a sword –- to attack those who obstruct the nefarious plans of powerful people.

How does all this reflect on the head of the prosecuting authority? Are there grounds for him to resign?

I take no position on whether Abrahams should resign. Many prosecutors make decisions to withdraw charges for a host of reasons, some of them quite legitimate. The better route would be an inquiry into what went into the decision to charge the minister and the two others in the first place. Was it malice? Incompetence? A conspiracy?

An inquiry would highlight whether Abrahams and his team are fit to run the nation’s prosecuting authority.

What needs to happen to prevent a replay of similar situations in future, and rebuild confidence in the NPA?

An inquiry, not necessarily judicial, but led by credible individuals trained in the law, needs to be held into the fiasco. It should be underpinned by a transparent process with unlimited access to a wide range of sources. Only such a concerted effort to clarify what has transpired will ensure that it is not repeated.

Penelope Andrews, Dean of Law and Professor, University of Cape Town. Images by GCIS, via Flickr.

This article first appeared in The Conversation, a collaboration between editors and academics to provide informed news analysis and commentary. Its content is free to read and republish under Creative Commons; media who would like to republish this article should do so directly from its appearance on The Conversation, using the button in the right-hand column of the webpage. UCT academics who would like to write for The Conversation should register with them; you are also welcome to find out more from carolyn.newton@uct.ac.za.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Related

Why South Africa's carbon tax should stay

24 Feb 2026

Republished

Cape Town’s wildflowers: six key insights from a new checklist

19 Feb 2026

Republished