Trauma interrupted: The role of acknowledging blame and responsibility

17 March 2014

During World War II, bystanders in the community of Grossröhrsdorf, a small East German village near Dresden, witnessed a Jewish family being taken away by the Nazis.

The parents, Curt and Regina Schönwald, became victims of the gas chambers that killed millions of Jews. But before being sent to Buchenwald, Curt, a decorated World War I soldier, was released to sell his business, a textile shop the family had owned since 1928. During that brief reprieve, the couple managed to send their children, Heinz and Suze, to safety in America and what was then Rhodesia.

But the community of Grossröhrsdorf never forgot the family, and for decades lived with the shame of not acting as their friends and neighbours were taken away to certain death.

Captured by the story, German theologian Pastor Norbert Littig spent 25 years researching what happened to the family – a complicated endeavour, given that the German Democratic Republic (GDR) did not allow this type of research – and began a reconciliatory process, piecing together memories from the bystanders.

This work inspired a book, and the community later issued a formal apology, the Grossröhrsdorf Apology, acknowledging their failure to protect the Schönwalds.

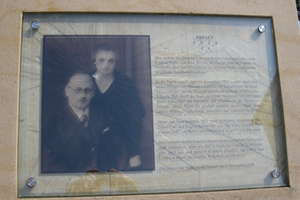

In November 2008 a memorial to Curt and Regina Schönwald was erected in the town during a week of "dignified remembrance". It reflected similar post-WWII reparation efforts, particularly by German Christians who'd also "stood by and watched", as a confession of their guilt. Organisations were formed to care for Jewish cemeteries and the aged, many of whom had survived the Holocaust.

Littig is now active in school exchanges that promote peace between Germany, Israel and Palestine. During his recent visit to South Africa in February, he addressed participants at UCT's 'Reconciliation, Intergenerational Trauma and Higher Education' colloquium.

Acknowledging blame: German theologian Pastor Norbert Littig, with a translator Dr Tania Katzschner, recounting his research on a World War II Jewish family taken by the Nazis as their fellow villagers looked on. The theme of his talk was apology, reparation, and forgiveness, delivered at the 'Reconciliation, Intergenerational Trauma and Higher Education' colloquium in February.

Acknowledging blame: German theologian Pastor Norbert Littig, with a translator Dr Tania Katzschner, recounting his research on a World War II Jewish family taken by the Nazis as their fellow villagers looked on. The theme of his talk was apology, reparation, and forgiveness, delivered at the 'Reconciliation, Intergenerational Trauma and Higher Education' colloquium in February.

The Grossröhrsdorf Apology is in some ways reminiscent of South Africa's own path to truth and reconciliation. South Africans also experience multiple levels of trauma as a result of the country's fraught past, compounded by current stigma and shame around HIV, race, class and sexual orientation, said HAICU director and colloquium architect Dr Cal Volks.

Should South African 'bystanders' be doing more to acknowledge what did or didn't take place in South Africa, asked Volks? "Do we need more fora and facilities for discussion, healing, and reconciliation in appropriate settings, including institutions like UCT?"

Littig's presentation, delivered with the help of translator Dr Tania Katzschner, was especially close to home for Volks – who is one of Suze Schönwald's granddaughters.

Volks only heard more detail of what happened to her family from Pastor Littig later on in life.

For her, the burden of acknowledgment is felt at two levels: as a descendant of German Jews, and as a white South African. This experience has only deepened her exploration of the many narratives around the possible impact of intergenerational trauma and the need to address it at Higher Education Institutions.

The full weight of trauma, whether at the hands of Nazis or perpetrators of apartheid atrocities, is often experienced by the second and third generations, said Ken Wald, professor of American Jewish Culture and Society at the University of Florida, in a Skype interview. Wald, too, is a survivor of intergenerational trauma, and a descendant of Heinz Schönwald.

For both Volks and Wald, learning the story of Curt and Regina Schönwald returned a lost piece of history, and gave them the chance to make a level of peace with the past – interrupting the transmission of trauma from one generation to the next.

Volks has since visited the memorial to Curt and Regina and is acutely aware of the importance of acknowledgement and responsibility.

"Acknowledgements of the failure to interrupt violence are important. They have the potential to facilitate 'empathic repair' by allowing the victims and perpetrators to engage with each other."

Story by Helen Swingler. Pictures by Raymond Botha.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.