Where are our graduates?

23 September 2013Pathway from university to world of work is illuminated by useful study, says Crain Soudien

Prof Crain Soudien, Deputy Vice-Chancellor, responsible for transformation and social responsiveness at UCT.

Prof Crain Soudien, Deputy Vice-Chancellor, responsible for transformation and social responsiveness at UCT.

The issue of graduate employment is of considerable public interest, but there is surprisingly little data to inform opinion on the matter. Not all universities in this country routinely carry out surveys to determine graduate destinations, and in particular, to establish whether and how their graduates find employment - as is the case in many other countries. Only one national-level tracer survey has been conducted in the past decade.

In 2005, the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) undertook a tracer survey of the 2003 cohort of 'drop-outs' and graduates at seven public higher education institutions. They reported an overall unemployment rate among their sample population of 32%, which is considerably higher than the average of 5% for Europe in the same period and 16% reported for Brazil.

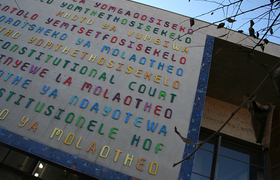

The four universities in the Western Cape - Cape Peninsula University of Technology, University of Cape Town, Stellenbosch University and University of the Western Cape - under the auspices of the Cape Higher Education Consortium (CHEC) decided to carry out a Graduate Destination Survey (GDS) in 2012, in order to determine levels of graduate employment and to better understand the different pathways that our graduates follow from university to the world of work.

We chose to survey the entire cohort of 24 710 graduates who had received certificates and diplomas, undergraduate degrees and postgraduate diplomas and degrees in 2010. They were surveyed in 2012 - two years after graduation. Their responses were captured either online or telephonically. We achieved a 22.5% response rate, which is comparable to similar surveys conducted internationally. The survey explored seven different graduate pathways: young, first-time entrants into the labour market; 'mature' graduates who had prior work experience; self-employed graduates; graduates employed in the informal sector; unemployed graduates looking for work; continuing to study full-time; unemployed but not looking for work (e.g. caregivers). While some of the findings of the survey were not unexpected, others have been surprising.

We found total employment to be high, at 84%. Almost half of the employed graduates found work in the public sector, which is clearly playing an important role, particularly by employing significant numbers of women professionals as well as African and coloured graduates. Sixty-one per cent of whites and 58% of Indians were employed in the private sector, compared to only 35% of African and 44% of coloured graduates. These figures, read in conjunction with the finding that white students were the most successful group in tapping into social networks to find employment, raise important questions about employment practices within the private sector, which need further investigation.

While the majority of graduates were employed as professionals, of concern is the number of graduates facing under-employment and/or low-skill work. For example, 26.2% of 'Business and Commerce' graduates were working in clerical jobs, as were 14.5% of Humanities graduates. In addition, just under 1% of the cohort was employed in the informal sector, most probably as a protection against unemployment. These patterns of employment need to be closely monitored in the coming years.

The rate of self-employment was low at just over 2% of the cohort, but comparable with international data.

Unemployment was measured at 10%, which is significantly lower than the 32% reported by the HSRC in 2005. However, behind this overall percentage lie some extremely disturbing patterns, which, in considerable measure, point to the perpetuation of historical inequalities in the graduate labour market: unemployment was at 19% for African graduates; high levels of unemployment were seen among graduates from Limpopo (19%), North West (17%), Eastern Cape (15%) and Mpumalanga (15%); unemployment was at 16% for CPUT graduates, many of whom have qualified with vocational higher education diplomas and certificates; 19% and 14% of unemployed graduates came from township and rural village secondary schools respectively; and 16% of those who received E-H symbols in matric maths were unemployed.

It came as no surprise that race emerged as statistically the strongest 'socio-demographic' predictor of employment. Furthermore, unemployment is a problem particularly facing young people. 72% of the cohort's unemployed graduates were 25 years and younger, while only 8% of the unemployed were older than 36 years of age.

The GDS highlighted two very positive features of the 2010 graduate cohort.

Firstly, 31% of the cohort continued to study either full- or part-time after their qualification in 2010. This is high, by all accounts. In a 2006 graduate destination survey of 12 European countries, the continuing higher education cohorts varied from 20% in France to 4% in the Czech Republic. Western Cape graduates gave was personal fulfilment as the main reason.

Secondly, we found that 34% of the cohort was employed in the formal economy prior to the start of their studies, which is a significant measure of the determination of people to study while working.

Migration of skilled labour is a phenomenon which is strongly associated with the acquisition of higher education qualifications. About 10% of graduates lived outside of South Africa prior to coming to study in the Western Cape and would in all likelihood comprise international students. In contrast, only about 6% of graduates indicated that they lived outside South Africa after graduation. This represents a net gain of skilled personnel. While this is most encouraging, a further 5% of our respondents indicated that they would consider leaving South Africa permanently some time in the future. Another concern was the high degree of uncertainty amongst graduates (26%) about whether to stay in the country or leave.

The GDS is a valuable instrument for providing a systemic view of how higher education works in relation to graduate labour. However, graduate destination surveys can only measure medium- to long-term trends if systematically repeated every five years on a national scale. We hope that the GDS conducted by the four Western Cape universities will be a catalyst for a similar study conducted on a national basis.

The full and abridged versions of the GDS report can be accessed on the CHEC website.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.