'Ultimate' botanist Skelton flies South African flag high

24 April 2013 | Story by Newsroom

2012 was something of an annus mirabilis for PhD botany student Rob Skelton.

First, he flew the South African flag as part of the national Mambas team (in which he's known by the tag 'Helter') at the Ultimate world championships in Japan. As an encore, he netted the Australian Journal of Botany's Best Student Paper of 2012 award.

The award sets a precedent for a researcher with plans to pursue postdoctoral studies. Along this path lie many more papers.

"But it's good to get the recognition," said the plant scientist. "It helps me get my research and ideas out there."

'Out there' sums it up. This international journal is a repository of leading plant science research in Southern Hemisphere ecosystems.

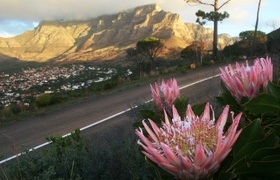

Co-authored with UCT's Professor Jeremy Midgley and Associate Professor Mike Cramer, and the University of KwaZulu-Natal's Professor Steve Johnson, Skelton's winning piece came out of his MSc work on leaf pubescence in Leucospermum, a genus of some 50 species of evergreen flowering shrubs in the family Proteaceae.

Leucospermum species are common to the scrub and mountain slopes of the Cape Floristic Region - and probably best known for their 'pincushion' flowers. (And there's even an Australian connection: the genus is closely related both in evolutionary terms and in appearance to the Australian genus Banksia.)

Their tough and leathery leaves are either glabrous (smooth) or pubescent (hairy). Initially, Skelton had wanted to show that the reason for this difference was linked to water economy, and then move on.

"The view at the time was that increased cover, or hairiness, reduced water loss."

But his findings didn't align with the water conservation theory: surprisingly, the smooth-leafed sub-species lost less water.

He then had to develop and test alternative hypotheses for the functional significance of leaf pubescence. The silvery appearance of hairy leaves led him to investigate whether pubescence could act as a kind of reflective layer.

"Plants can get too much light," Skelton explained. The hairiness could act as a natural sunscreen.

His results showed that pubescent leaves do reflect more light, and that this reduces light-induced damage to the leaf. He also showed that hairy species were more common in drier, hotter environments; this led him to a link between aridity and pubescence.

"The hairy leaf is a radiation-protective trait, a way of reducing light-induced reduction in the photosynthetic capacity of a plant

On top of that, pubescence - by increasing the reflection of light from the leaf - also cools the leaf in stressful times of little water.

"As you move towards drier environments, plants are able to rely less on water for cooling, and use pubescence instead. So it's an adaptation to extremely dry habitats."

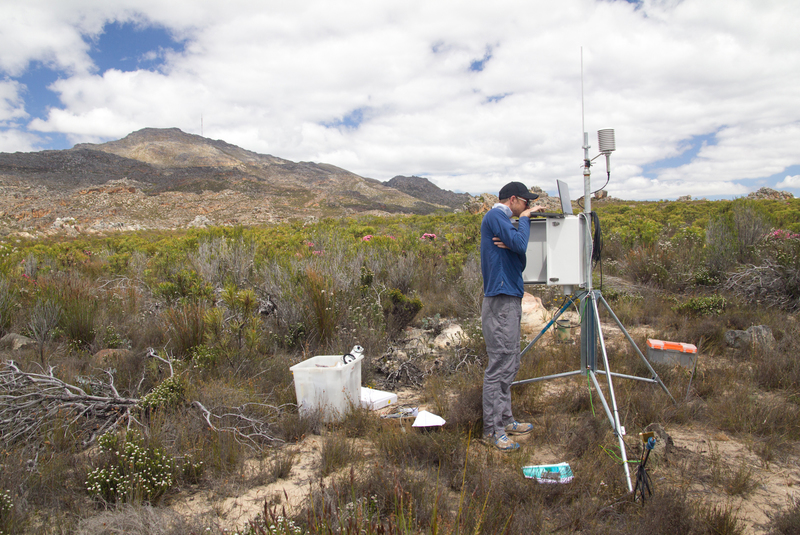

Skelton's work has broader implications vis-á-vis climate change and encroaching aridity in the Cape Floristic Region. His current fieldwork takes him on bi-monthly excursions to camp out at a remote site near Jonaskop, among the highest peaks of the Riviersonderend Mountains ("It's pretty cold there at the moment!"), private land bordering the Cape Nature Reserve, with limited public access.

Limited is good, he says.

"We want to understand what plants are doing outside of human interest.

"We now have a finer-scale-understanding picture of what variables plants are responding to. Determining which variables are important to which groups will tell us which plants will be vulnerable to climate change."

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.