Virtual heritage

09 May 2005

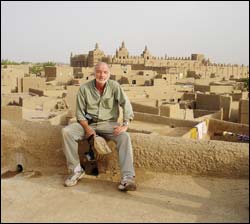

For posterity: Heinz Rüther, Professor of Geomatics, photographed at Djenne.

UCT's Professor Heinz Ruther has been documenting these sites, creating a digital archive for generations of scholars.

While architectural sites have been traditionally documented using photographs, two-dimensional plans and elevations, modern technology makes it possible to create three-dimensional computer models and visualisations, integrated with GIS and database technology.

"Documentation of these heritage sites has moved into the digital era and the third dimension," Rüther adds.

At his computer in the geomatics department, the specialist in architectural photogrammetry shows just why this documentation is important.

He pulls up a 3D model of a fortress at the World Heritage Site of Kilwa Kisiwani in Tanzania.

Intact two years ago, the archway has since collapsed.

The coral stone chunks that once formed the structure have disappeared, probably incorporated into the walls of new dwellings on the island.

He's concerned that other parts of the fortress will suffer a similar fate.

Developments like this prompted Rüther to propose the development of a digital archive of spatial and non-spatial data on Africa's heritage.

After years of chasing funding, Rüther has secured a grant of US$550 000 (around R3.5-million) from the Andrew W Mellon Foundation.

He will now be able to document 10 sites over the next three years, and hopes to continue with others after the first phase.

Named the African Cultural Heritage and Landscapes Database, this is a joint UCT- Aluka project.

(Aluka is part of an international Ithaka initiative to create an online archive of international scholarly resources).

Aluka is organised around three themes: Struggles for Freedom in Southern Africa, African Plants, and African Cultural Heritage, Rüther's brainchild.

The objects of the heritage documentation project are mosques and churches, fortresses, castles, palaces and historical cities, many losing the battle against time and climate, economical pressures - and vandalism.

It's a highly technical set of tools Rüther works with and he is supported by two computer scientists.

His approach integrates photogrammetry, remote sensing, conventional surveying, Geographic Information Systems, GPS and 3D visualisation to produce and present virtual models of these sites and buildings.

The spatial data are associated with a GIS for each site and integrated into a database.

The non-spatial content of the database will be gathered by Aluka, guided by a team of African historians and archaeologists.

This database will be available online for research, educational and cultural purposes.

A recent grant of US$75 000 from the Mellon Foundation has added a state-of-the-art Leica HDS3000 Laser scanner to the team's toolbox.

In a hybrid approach, the scanner is combined with photogrammetry.

Millions of accurate points are determined on a given structure's surface and overlaid with photographic texture.

"The result of this approach is a metrically-accurate, three-dimensional, computer model, a process akin to reverse engineering," Rüther explains.

The UCT team is also developing improved methods to combine laser scanning and photogrammetry.

"The resulting 3D computer model can be used to create virtual-reality environments, ground plans, elevations, 3D line models, digital ortho-photos, all integrated into the framework of a Geographic Information System and a database."

Importantly, the model allows researchers to take accurate measurements of structural detail directly on the computer screen and to monitor structural changes and the deterioration of surfaces over time.

"This data will assist antiquities authorities manage sites and plan conservation and restoration activities."

Rüther is a self-confessed African adventurer.

In his final year at school he hitchhiked from Germany through the Sahara to Tamanrasset in southern Algeria.

"I told my parents I was going to Spain."

This first encounter with Africa, followed by other similar experiences during his university years, triggered an abiding passion for the continent, its vast spaces and secluded places.

"I hope that the Heritage Project will contribute to the real and 'virtual' preservation of Africa's past."

Over the years, he has journeyed to some 30 countries - by small plane, helicopter, camel, 4x4 and dhow - to some of the continent's remoter and more inhospitable areas.

His travels have not always been plain sailing.

He was arrested three times and jailed for short periods in Zambia, Algeria and Zimbabwe.

His crimes? Asking directions from a soldier or unknowingly photographing government buildings.

For the past three years he has been working in Kilwa Kisiwani, a World Heritage Site that holds a key to understanding the Swahili culture and the Islamisation of the east coast of Africa.

Much of the once great city has been lost to time and erosion.

Only complex ruins remain.

With their irregular features, these represent an exceptional challenge to 3D modelling.

"I use Kilwa as a worst-case scenario to test these technologies and methods."

He has already documented the fortress and the Great Mosque of Kilwa.

These form the first components of the African Cultural Heritage and Landscapes database.

The remains of the Great Palace, the Husuni Kubwa, and Kilwa's Makutani palace, as well as an urban complex with houses, a public square, burial grounds, mosques and city walls in nearby Songo Mnara, will have to wait for a later phase of the project.

Rüther and his team have just returned from Timbuktu and Djenne, where they worked in cooperation with the Direction Nationale de la Patrimoine Culturelle of Mali on the documentation of the Great Mosques of these two historical cities.

His next field campaign will take him to Ethiopia, where he will document the World Heritage Sites of Lalibela and Axum.

He has already conducted a pilot study of Bet Giyorgis, one of the rock-hewn churches at Lalibela, built by King Lalibela in the 13th century.

He now plans to complete work on Bet Giyorgis and some of the other 10 rock churches of Lalibela.

In Axum, Ethiopia's most ancient city and, as legend has it, home to the original Ark of the Covenant, he will record the stele field.

(Stele are upright stones with sculpted or inscribed surfaces, used on the face of buildings.) Documentation fieldwork can be very demanding and is often performed in complicated conditions in difficult environments.

The mosque in Djenne required some 50 scans, some taken in temperatures of 45oC and others at night by torch light, with the team having to move the heavy equipment out of sight for each of the daily five prayer sessions.

One night's scanning operation was halted when a group of angry Djenne residents gathered around the three-man UCT team and their laser arsenal.

"The very prominent, fast-moving green laser dot scanning the mosque's wall had attracted their attention and our group was accused of evil doings," Rüther explained.

The people of Djenne were unaware that the team had permission to enter the Great Mosque, which is closed to non-Muslims.

A quick retreat was followed by discussions with the Chef de Village and the Imam resolved a somewhat volatile situation.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.