Magubane ensured that apartheid was not underexposed

16 June 2016 | Story by Newsroom

“A struggle without documentation is no struggle.”

So said Peter Magubane, the legendary anti-apartheid photojournalist who used his lens to expose apartheid's brutality to the world.

Magubane was speaking at the Humanities graduation ceremony on 15 June, the penultimate of a bumper June graduation season for UCT. More than 300 graduands became graduates, and UCT took the opportunity to congratulate both the students and some outstanding members of the arts and social sciences communities.

A day to salute creative genius

Emeritus Professor El Anatsui, a sculptor known globally for his post-independence experimental style, was conferred a Doctor of Fine Arts, honoris causa, for a sterling career in the arts.

Anatsui has been described as “the most significant living African artist”, said Deputy Vice-Chancellor Professor Sandra Klopper, who delivered the citation.

Anatsui retired from a professorship in sculpture at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, in 2011, and has become well known to South African art students. His work made an important contribution to the training of local artists, particularly at universities.

Man's Cloth, one of El Anatsui's most famous works, is made entirely from recycled bottle tops. Photo by Hahnchen, Wikimedia Commons.

Man's Cloth, one of El Anatsui's most famous works, is made entirely from recycled bottle tops. Photo by Hahnchen, Wikimedia Commons.

The innovative Anatsui built a reputation for experimenting with new concepts, such as his famous bottle-top sculptures. He once said: “I don't believe in artworks being things that are fixed. With the bottle caps now I don't do any drawings. You might be making yourself a slave to an idea. But I want to enjoy the freedom of shifting around things.”*

His artworks, including the huge, tapestry-like installations made from bottle tops, grapple with themes such as power, migration and the environment.

“My work has kind of tried to revolve around the history of the continent of Africa,” said Anatsui. “These bottle tops have served as a link between my continent, Africa and Europe. Drink was one of the prime objects that they brought.”*

With major international acclaim comes prestigious awards. Two that stand out are the Visionaries Artist Award from the Museum of Arts and Design in New York City, which Anatsui received in 2008, and the 2009 Prince Claus Award from the Netherlands. He also received the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennale in 2015.

“If you've never had the pleasure of seeing one of his works, do yourself a favour and google him,” said Professor Sandra Klopper.

Read Prof Sandra Klopper's oration …

Watch a video …

(part of the El Anatsui documentary film currently in production, and coming out in 2017)

From left: Dr Litheko Modisane, winner of the UCT Book Award; Assoc Prof Jay Pather, winner of the UCT Creative Works Award; and Emer Prof El Anatsui, who was conferred the degree of Doctor of Fine Arts, honoris causa.

From left: Dr Litheko Modisane, winner of the UCT Book Award; Assoc Prof Jay Pather, winner of the UCT Creative Works Award; and Emer Prof El Anatsui, who was conferred the degree of Doctor of Fine Arts, honoris causa.

Productions and publishing

Two UCT scholars were honoured for their excellent work at the ceremony.

Associate Professor Jay Pather, director of the Gordon Institute for Performing and Creative Arts, won the UCT Creative Works Award for Qaphela Caesar, a theatrical re-imagining of Shakespeare's Julius Caesar.

Meanwhile, Dr Litheko Modisane, senior lecturer in the Centre for Film and Media Studies, won the 2016 UCT Book Award for Renegade Reels: The Making and Public Lives of Black-Centred Films.

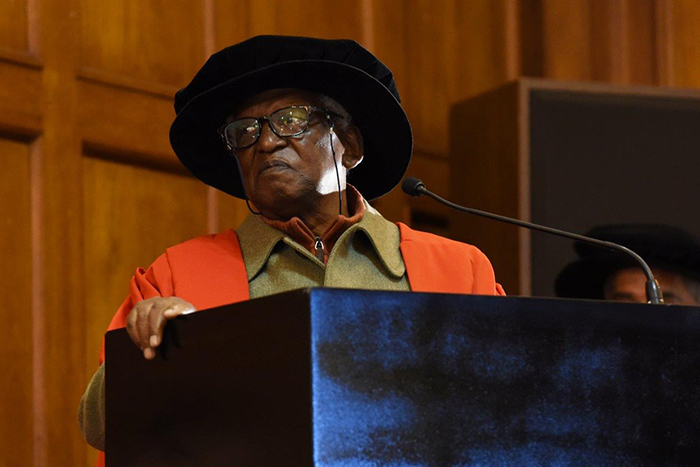

Peter Magubane speaks

Legendary photojournalist Peter Magubane gave the keynote address at the Humanities graduation ceremony on 15 June 2016.

Legendary photojournalist Peter Magubane gave the keynote address at the Humanities graduation ceremony on 15 June 2016.

Legendary photojournalist Peter Magubane gave the keynote address at the graduation ceremony. The fearless anti-apartheid activist took up photography in high school, said Deputy Vice-Chancellor Professor Anwar Mall.

Magubane's first photographic job came at Drum magazine, where he had first been employed as a driver and messenger. Drum was renowned as an opposing voice to the apartheid government's tyranny in the 1950s, and Magubane became part of a revered team of photographers that included Jürgen Schadeberg, Alf Khumalo, Ernest Cole and Bob Gosani.

He documented most major political events in South Africa during that period, including the uprising by schoolchildren in Soweto in 1976 when thousands took to the streets to protest against Bantu education, only to be met by police dogs and bullets.

As he rose to give his speech, the octogenarian Magubane got a rousing ovation, which he saluted.

The audience was stirred by a montage of some of Magubane's famous photos taken in Soweto on June 16, 1976.

What struggle without documentation?

He recalled a moment from June 16, 1976: “When I picked up my cameras and pointed it at these boys who were coming towards me, they said, 'No, no, no'. I said, 'Yes, yes, yes. A struggle without documentation is no struggle.' ”

Magubane's images were published around the world.

“I think I was there as a messenger, and as a messenger, I did my job.”

But his job was not without its risks. Having exposed the apartheid regime's brutality with his camera, he took a policeman's baton on the nose after refusing to destroy his film.

“I knew my nose would heal, but my historical images were lost forever.”

One encounter typified Magubane's relationship with the police.

“If you don't leave here, k----r, I'll kill you,” warned an apartheid foot soldier. “I just went around the corner and came back.

“Because I was prepared to die for the cause, I did not give up. To make the world see what apartheid was. How black people lived. I take my hat off to those photographers who died, who gave their lives for the cause.”

But he was not one to stand back and watch his fellow photographers being violated. Magubane gained a reputation for putting his camera aside to save the lives of the people around him.

He was repeatedly assaulted by apartheid police. But being beaten during his multiple stints in detention, shot in the legs with buckshot, and having his house burnt down did not deter him from his mission.

Nor could being kept in solitary confinement for months at a time, nor even the ban from photography that followed. In fact, Magubane's famous shots of the Soweto uprising were taken while he was under a banning order from the apartheid state.

“I told myself that no one is going to tell me what to do. I'm going to do my work whether I get arrested or not; I am prepared to die.”

Because of his dangerous work, his family constantly pleaded with him to put his camera down. But Magubane's response was always the same: “I'm already injured.” So he kept going.

Along with the Soweto uprising, Magubane photographed the Sharpeville massacre, the Rivonia Trial and countless political protests.

Magubane might have put his struggle camera down – “where there is blood, I don't photograph now” – but the fire remains.

Story Yusuf Omar. Photos Michael Hammond.

*El Anatsui, from Fold Crumple Crush: The Art of El Anatsui, a film by Susan Vogel, 2011. (Online transcript viewed at susan-vogel.com/Anatsui on 15 June 2016.)

See Peter Magubane's presentation slides:

Watch the recorded ceremony:

See a selection of pictures from social media:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.