Africa Day celebration highlights African identity, resilience, and ownership in health sciences

21 May 2025 | Story Myolisi Gophe. Photos Lerato Maduna. Read time 9 min.

The early Africa Day celebration at the University of Cape Town (UCT) on 19 May was more than just a ceremonial occasion – it served as a powerful call for reflection, unity, and decisive action.

Hosted by the Faculty of Health Sciences’ (FHS) Pan African Health Sciences Forum under the theme “Africa at a Crossroad: Taking Ownership of Clinical Research and Healthcare for Generational Change”, the event took place at the Neuroscience Institute. It brought together healthcare experts and students to reflect on the progress made over three decades of democracy in South Africa, assess the current state of healthcare, and explore the road ahead.

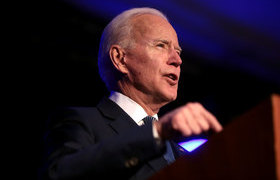

The discussion was particularly timely given the growing concerns about the sustainability of healthcare provision and research, especially considering funding cuts to related projects in South Africa by the administration of United States (US) President Donald Trump.

In her welcome address, Associate Professor Tracey Naledi, the deputy dean for social accountability and health systems at the FHS, spoke with passion about the importance of Africa Day, rooted in the vision of Pan-Africanism: a belief in unity, justice, self-determination, and African agency. “It’s not only about celebrating excellence, but reclaiming power over our narratives, our resources, and our futures,” she said.

Associate Professor Naledi highlighted the crucial role that the faculty is playing in building African capacity, and that the Pan African Health Sciences Forum was created to support the diverse community.

“At a time of plague, we did not flee. We did not hide. We did not separate ourselves.”

While the current healthcare situation is in trouble, there are many reasons to celebrate the gains made, and to be optimistic about the future.

Delivering a keynote lecture that spanned the history, present realities, and future uncertainties of HIV and tuberculosis (TB) work in South Africa, Professor Linda-Gail Bekker, an acclaimed clinician-scientist and an advocate for global health equity, offered a sobering reminder of what is at stake: not only millions of lives already saved, but also the fragile systems that sustain those gains.

“When the history of AIDS and the global response is written, our most precious contribution may well be that at the time of plague, we did not flee. We did not hide. We did not separate ourselves,” she said.

A personal and collective journey

Fully soft-funded since 2000 and the principal investigator of UCT Clinical Trials Unit since 2005, Professor Bekker has devoted her career to HIV and TB research. Today, her unit employs over 400 professionals, including clinical, behavioural, laboratory, pharmacy, data, and community research experts.

In revisiting the past, Bekker acknowledged the failures and painful legacies of political denialism, particularly in the early days of the HIV epidemic in South Africa. She noted how the virus – first viewed as a Western problem – soon exploded into a generalised epidemic in the 1990s, costing millions of lives and exposing deep social inequities.

Chris Hani’s 1992 warning of an “epidemic disaster” was tragically prophetic, she reminded the audience. But even amid this devastation, visionary South African scientists began modelling the epidemic’s trajectory, revealing its disproportionate impact on women and highlighting its feminisation. “We were watching people die. And all we could do was count.”

Breaking barriers, building solutions

Despite the grim context, the past three decades have also been a story of scientific resilience and community activism. From proving that Africans could adhere to antiretroviral therapy (ART) to demonstrating that nurses and lay counselors could safely deliver care, the South African response helped reshape global treatment paradigms.

“We saw Lazarus moments. People came back from the dead.”

One image that Bekker shared was that of a once-dying staff member who began ART at a dedicated clinic in Gugulethu – and survived. “We saw Lazarus moments. People came back from the dead.”

She emphasised how HIV and TB, long treated as separate epidemics, were in fact deeply intertwined. HIV-triggered immune suppression opened the door for a sixfold increase in TB cases across South Africa. Cape Town today sees more TB infections than the entire United Kingdom (UK), US, and Europe combined.

A triumph at risk

Thanks to global and local momentum, including the World Health Organization’s 3x5 initiative (target of providing ART to three million people living with AIDS in developing countries and those in transition by the end of 2005), President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), and the Global Fund, South Africa now has nearly six million people on treatment. Globally, 30 million are on ART, with 21 million lives saved and life expectancy restored in many parts of the continent.

Yet, these victories are now in jeopardy.

On 20 January 2025, the newly inaugurated US administration imposed a freeze on PEPFAR funding. By 27 February, many USAID cooperative agreements were terminated. PEPFAR was moved under the State Department, and the $460 million annual budget for South Africa was abruptly cut.

The consequences were immediate. Staff retrenchments, programme shutdowns, and the halting of dozens of ongoing HIV and TB clinical trials, including many involving prevention and treatment innovation, followed.

An endangered legacy

Over the past 30 years, South Africa has built one of the world’s strongest clinical research infrastructures for HIV and TB, spanning first-in-human trials to large-scale community implementation studies. Its institutions rank alongside global giants in research output, and its insights have directly shaped international treatment and prevention strategies.

In a 2019 analysis, South Africa ranked third globally, after the US and UK, for peer-reviewed publications in HIV/TB, and first in terms of citations per article. UCT led the list.

But that ecosystem, according to Bekker, now stands on shaky ground. “We’ve become dependent on federal US dollars. And the rug has been pulled out.”

She said in the absence of a replacement for PEPFAR, South Africa could see over half a million new infections and an equal number of deaths in the coming years – at enormous human and economic cost.

A call to action

The future, Bekker insisted, must be defined by innovation, political commitment, and a renewed push for prevention. “We cannot rely on treatment alone. Prevention must come to the forefront. And we have the tools.”

From injectable pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to differentiated service delivery and community-based care models, she believes the answers are within reach. But reaching the “hardly reached” – those left behind by stigma, criminalisation, and structural inequality – remains the biggest challenge.

Panellists, who took stage after her talk, agreed.

Professor Digby Warner, the director of the Institute of Infectious Disease and Molecular Medicine (IDM), noted that in every crisis there’s an opportunity, and stressed the importance of not returning to outdated systems. “We recognise … the dependencies and inequities we were complaining about six months ago are not necessarily things we want to reinitiate,” Professor Warner said.

He argued for more deliberate and strategic approaches going forward: “We can be better and more deliberate in how we enable research in this environment. Our real power here is the coincidence of infectious, non-communicable diseases, and other social factors. We really have to take advantage to change our local experience of the health challenges that we face.”

“If we come together … if we actually work on South–South collaborations … we can do better.”

Reflecting on local capacity, the head of the Department of Medicine at UCT, Professor Mashiko Setshedi, said: “COVID did the same and we actually ended up doing research for vaccine development – unprecedented, but we did it.” She emphasised the power of collaboration: “If we come together … if we actually work on South–South collaborations … we can do better. There’s a lot we can look forward to … to actually do better than we thought we could.”

The chief executive officer of the South African Medical Research Council, Professor Ntobeko Ntusi, echoed their sentiments and described the current funding crisis as both a challenge and a turning point: “It’s a moment where perspective really matters. Funding has been withdrawn, operational aspects of research interrupted, individuals are losing livelihoods, postgraduate students are losing training opportunities. We’re likely to see many patients suffer greater morbidity and mortality.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.