South Africa isn’t doing enough to provide HIV prevention treatment for mothers: why it needs to

01 December 2021 | Story Dvora Joseph Davey and Linda-Gail Bekker. Photo Uwe Baumann, Pixabay Read time 6 min.

A global target for the elimination of mother to child transmission of HIV globally was set in 2015. The ambitious target of the Joint United Nations Programme (UNAIDS) was to reduce new infant HIV infections by 75% by 2020. This is equivalent to reducing new infections to under 1%.

South Africa has the largest number of people living with HIV in the world: over 7.7 million. The country also has the largest HIV epidemic in pregnant women. Over one-third of pregnant women have HIV, contributing to one of the highest rates of vertical transmission (HIV from mother to infant), estimated at 3.9% in 2020.

South Africa has been committed to achieving the elimination of maternal to child transmission of HIV since 2015. It introduced policies that give lifelong antiretroviral therapy to all pregnant women living with HIV. But, over six years later, new infections in pregnant women continue at a high rate.

Since 2017 the World Health Organisation (WHO) and several national HIV programmes have recommended offering daily oral preventive medication technically known as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to pregnant and breastfeeding women at risk of getting HIV. PrEP is the use of antiretroviral therapy to prevent the acquisition of HIV in people who are not living with HIV. The recommendation is based on a large body of safety data from women living with HIV who used the same drugs as treatment during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

We estimate that over 90 000 infants will acquire HIV in the next 10 years.

Not offering preventive treatment to women not living with HIV but who are at risk of HIV acquisition undermines the efficacy of all of the South African efforts to eliminate mother to child transmission of HIV. It is urgent and overdue to implement PrEP in pregnancy and during breastfeeding. Failure to do so in the face of proven prevention interventions allows ongoing avoidable HIV infection among women in South Africa with the added high risk of transmission to their infants.

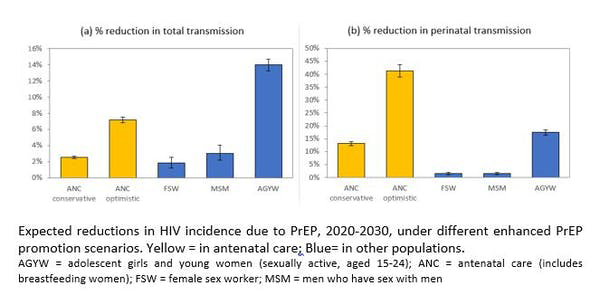

In the absence of PrEP, we estimate that over 90 000 infants will acquire HIV in the next 10 years. Our team’s mathematical models estimate that by providing PrEP to pregnant and breastfeeding women in South Africa, we could reduce maternal and infant HIV incidence by upwards of 136 000 in the optimistic scenario. This is similar to estimates of PrEP provision among female sex workers and men who have sex with men.

Preventing new infections

There are approximately 1 million live births in South Africa annually. Around 70% – representing 700 000 live births – involve women not living with HIV. Many of these women are at very high risk of HIV acquisition and infant HIV transmission due to a combination of biological and behavioural factors. These include having partners living with HIV, multiple partners and frequent condomless sex.

These women have the right to access PrEP to protect themselves against HIV during this high risk period. Currently, in South Africa, around one in three infant infections arise from mothers who acquire HIV during pregnancy or breastfeeding.

South Africa will continue to struggle to reach the elimination goals unless the government ensures that women at risk of HIV exposure can access an effective biomedical prevention option during their pregnancy and breastfeeding journey.

Ongoing studies show a high receptiveness to PrEP among South Africans. This suggests that PrEP can be integrated into antenatal and postnatal care. A recent study we did in Cape Town demonstrated that over 85% of women without HIV accepted PrEP at first antenatal care visit, and over 70% continued on PrEP at month one, and 60% at month three.

Those who were at higher risk of HIV acquisition were more likely to continue on and adhere to daily PrEP. The identifiers of higher risk are a sexually transmitted infection, a partner living with HIV, or having more than one sex partner. The Cape Town study also demonstrated the safety of providing PrEP in this population, in line with other studies in the region.

Antenatal care uptake in South Africa is high, reaching over 95%. This presents a perfect opportunity to offer PrEP to women seeking routine services. Expanding PrEP implementation to include pregnant and breastfeeding women will further support South Africa’s efforts to reach its ambitious goals of eliminating infant HIV.

Expanding existing programmes

Oral PrEP is scaling up among pregnant and breastfeeding women in sub-Saharan Africa with notable implementation successes in Kenya and ongoing demonstration projects in South Africa, Lesotho, Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

The South African government should support the immediate training of healthcare providers and integration of PrEP into antenatal and postnatal care for all women at risk of HIV. All pregnant women who test HIV-negative at their first antenatal visit should receive the offer to start PrEP. This must be accompanied by comprehensive HIV prevention services, including counselling to support them to take daily PrEP while pregnant and breastfeeding.

Maternal HIV programmes that include primary prevention of HIV through the use of PrEP to pregnant and breastfeeding women at high risk of HIV are key to realising the goal of the elimination of HIV in infants.

Dvora Joseph Davey, Honorary Senior Lecturer in the Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, University of Cape Town and Linda-Gail Bekker, Professor of medicine and deputy director of the Desmond Tutu HIV Centre at the Institute of Infectious Disease and Molecular Medicine, University of Cape Town.