Jellyfish Mating Day: an in-joke that became a tradition

03 November 2020 | Story Emer Prof Jenny Day. Read time 10 min.

On World Jellyfish Day, 3 November, Emeritus Professor Jenny Day writes about an in-joke at the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) zoology department that became a tradition 50 years ago: national Jellyfish Mating Day (JMD).

It was celebrated annually in the Department of Zoology for many years. The story that follows relies on memories from 50 years ago, so some of the incidents have taken on the aura of myths and, like myths, are often more true than the truth! They certainly do describe the departmental zeitgeist in those far-off days.

I am happy to acknowledge the contributions of many of the staff and students of the time: George Branch, Anna Crowe, Charles Griffiths, Colleen Moloney, Christopher McQuaid and Dave Muir all wrote to tell me of their memories. I have gladly plagiarised their notes.

Evading physics pracs

The story is that one Friday in late August 1970, several zoology students decided to bunk their practical and go to the beach instead. When they were asked the following Monday why they hadn’t been at the practical, they said that they had been celebrating Jellyfish Mating Day. They were forgiven by the lecturer concerned because the excuse was such a fine biological joke. (For non-zoologists, jellyfish are mainly broadcast spawners and don’t mate.)

“We were continually looking for excuses to evade physics pracs.”

Muir’s recollection was a little different, and he should be believed because he and McQuaid were the major instigators. He wrote: “The whole thing began in 1970 when I was (again) doing physics and was hanging together with a rowdy group of repeat students.

“We were continually looking for excuses to evade physics pracs and became aware that religious students frequently got holidays that we were not afforded, so we decided to make up our own and submit the requisite excuse notes. The first ever Jellyfish Mating Day was Friday, 31 August 1970.”

No matter how it started, JMD was celebrated in the zoology department each year for the next 20 years or more. At first it consisted of a few hand-drawn posters scattered around the building with jelly provided to staff by the third years. Later, more of the campus was decorated (much to the bewilderment of the less biologically literate on campus), students often staying up all night to make ‘jellyfish’, mostly from plastic bags.

Famously, while the current John Day Building was being built, two students climbed up one of the huge building cranes to leave a plastic-bag jellyfish dangling from the hook of the crane. In some years, students would arm themselves with jelly-filled balloons, which they threw at passers-by in University Avenue, invoking the bemused wrath of the victims.

Jellyfish spawn

Moloney recalled: “As third years (in 1982) we prepared jelly for tea, handed out Jelly Babies [and] decorated the department.”

According to McQuaid, “It reached its apogee when we eventually trained the second years to hand out Jelly Babies to the first years and decorated Jammie Hall with posters and jellyfish made from balloons.”

It must have been around that time that Branch was ‘kidnapped’ on one JMD and required to ingest ‘jellyfish spawn’, which – he thankfully acknowledged – was regular jelly made with a good dose of beer.

I asked my correspondents if they had any thoughts as to why JMD became such an important part of departmental life.

Muir again: “I think something about its innocent silliness and playful nature caught peopleʼs attention. In ... 1972 it was adopted in full measure by the Zoo II class ... I remember that I, along with John Boland, Jackie King and others, formed a sort of committee that planned the first truly organised JMD.”

It then became a yearly fixture. “By the time we were in honours, [it] had spread to the botany department as well, and then, as zoologists spread out to do graduate studies, several other departments like applied maths and even [the then government research institute] Sea Fisheries, also participated.”

Tradition, fellowship and community

As a continuing tradition, JMD had something about it that was intimately tied to a sense of fellowship and community that characterised the zoology department in those days, perhaps one reason that it is still remembered so fondly.

“It was as earnestly celebrated by the lab staff, for example, as it was by students and academic staff.”

It speaks of very real friendships that we enjoyed across age groups and academic status: “It was as earnestly celebrated by the lab staff, for example, as it was by students and academic staff,” wrote Muir.

“I was really amazed to learn that [the late] Alec Brown [the head of the Department of Zoology intermittently for many years] regarded it as an important part of departmental history. He included a reference to it in his history of the department and cited it as exemplary of the spirit of the department in those days.”

Griffiths reminded me that over the years there were several articles about JMD in the press, so its fame spread beyond mere academia.

Why did JMD die out?

Several academic staff members had gloomily predicted that the move to a beautiful, roomy new building (the one now occupied by the Department of Biological Sciences) in 1985 would spell the end of the departmental spirit, at least partly because the undergrads would become more removed from the staff and postgrads.

The demise of JMD did seem to coincide with a decline in camaraderie in the department. Did it grow too big? Too divided into small research units?

Remote fertilisation

So, if jellyfish don’t mate, how do they reproduce?

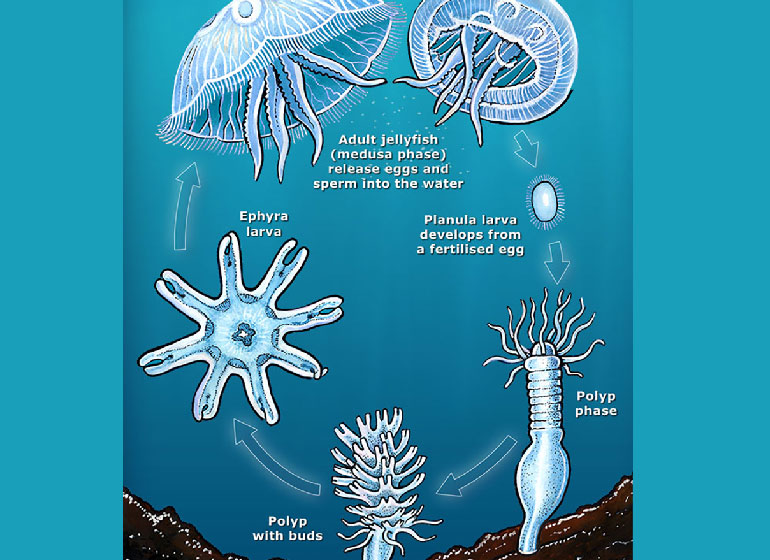

What follows is the textbook story, although jellyfish biologists are beginning to find that some species don’t really behave like this. Males and females of ‘regular’ jellyfish swarm together but don’t touch each other. They eject sperm or eggs into the sea, and fertilisation takes place when egg and sperm meet. In the more recently discovered jellyfish belonging to the species Copula sivickisi, the male and female entwine tentacles and then the male passes a package of sperm to the female who inserts it in her body where the ripe eggs are, and fertilisation takes place there.

(This article has been edited.)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.