Preserving cultural heritage through state-of-the-art technology

22 September 2020 | Story Anna Kent and Heinz Rüther. Photos Zamani Project team. Read time 7 min.

The Zamani Project is a research group at the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) School of Architecture, Planning & Geomatics in the Faculty of Engineering & Built Environment that records, showcases and spreads awareness of cultural heritage sites on the African continent and beyond. The project has a reputation for producing spatial heritage data of high accuracy and authenticity.

“Developing awareness of heritage supports a sense of belonging and also helps us to understand and respect the values of other cultures,” explained Emeritus Professor Heinz Rüther, the principal investigator at the Zamani Project.

Emeritus Professor Rüther’s deep interest in heritage has fuelled his 40 years of dedicated work in heritage documentation.

In 2001 Rüther founded the Zamani Project to help address the fact that heritage sites are often undocumented, or poorly documented, and many face threats of damage or destruction. A wealth of cultural heritage is at risk of being lost through sea-level rise, natural disasters, vandalism, cultural terrorism, war, mining, construction, poorly managed mass tourism and the ravages of time.

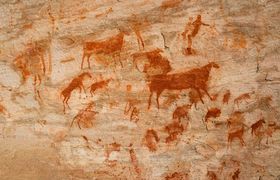

With the generous support of the Mellon Foundation, The Saville Foundation and Epic Games, and the use of software from Reality Capture and Epic Games, the Zamani Project team has documented more than 250 structures, rock art shelters and statues at 65 heritage sites in 18 countries across Africa, the Middle East, Southeast Asia and Europe.

They have collaborated with the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), World Monuments Fund, the Getty Conservation Institute and numerous researchers and heritage professionals worldwide.

“It’s not just a pretty picture – it’s an accurate representation of the site.”

At each site they create digital records using laser scanning and photogrammetry based on drone and terrestrial photographs, panorama photography and satellite images.

Bruce MacDonald, one of the chief scientific officers at the Zamani Project, explained: “We scan the object or structure with the laser scanner, but independently from that we survey well-defined points of the documented building and use those for quality control and as control points to place the models in their accurate geographical position. It’s not just a pretty picture – it’s an accurate representation of the site.”

Back in the office (or, since COVID-19, at home), the team then uses the data to generate 3D models, Geographic Information Systems, sections, plans, elevations and panorama tours, as well as site animations and virtual tours.

Collaborating with technology industries such as Zoller & Fröhlich, and using photogrammetry software from RealityCapture, the Zamani Project pushes boundaries of software and hardware, allowing improvements to be fed back into commercial software.

Accuracy for heritage conservation

The focus of the Zamani Project team is on producing data that is authentic and accurate, and which supports heritage conservation experts like Stephen Battle from World Monuments Fund in his work to preserve culturally sensitive sites.

In collaboration with World Monuments Fund, the Zamani Project undertook two field campaigns to document and conserve the rock-hewn churches of Lalibela in Ethiopia. There are 12 churches at the site, carved in stone out of the mountainside. In the second field campaign in 2017, Rüther and the team did a detailed follow-up survey of two of the churches to detect and quantify possible deformations in the rock structures.

“Usually, this area is closed to all but one or two priests,” said Battle.

It is a chapel that is carved underground, part of which is below a courtyard area. The morphology of the structure is complex, but Battle explained that by connecting all of Zamani’s created models of the site, they were able to understand not just the individual models, but also see for the first time how they fit together as a whole. This proved invaluable, giving insight into an area of roughly 30 cm of rock in between the top of the arch and the floor of the courtyard above, which was unstable.

“That was a revelation that changed how we did conservation in that particular area of the site. Without using the LiDAR [light detection and ranging] scanning techniques that Zamani uses, it would have been very difficult to establish that.”

Identity, laser scans and CGI

In August 2019 the Zamani Project team documented the House of Wonders in Stone Town, Zanzibar. This structure was built in 1883 for the second sultan of Zanzibar, Barghash bin Said.

In its day the House of Wonders was a celebration of modernity: it was the first building in Zanzibar to have electricity and the first in East Africa to have an elevator. It exhibited innovative architecture, using steel beams and concrete slabs to create high ceilings and hanging floors.

Friedrich Klütsch, a documentary filmmaker and the director of film company DEMAX, worked on site with the Zamani Project team for 10 days. DEMAX is producing a film series about the exchange that occurred between the Sultanate of Oman and East Africa over the centuries and is using the House of Wonders as a virtual exhibition space for the elements of this exchange.

“The House of Wonders is in great danger and is falling apart. It’s been neglected … [and] part of it has already come down,” Klütsch explained.

DEMAX is importing the Zamani Project’s data into software programmes to create 3D computer-generated imagery (CGI) for their film series.

“This is the first time we are using LiDAR scanning to this extent,” said Klütsch.

He hopes to establish a connection between the modern audience and history and heritage through his films.

Klütsch explained his choice to work with the Zamani Project: “I think their experience in working in Africa is essential. And they are using state-of-the-art equipment – we knew that from the technical side we would get what we needed.”

With their expertise in cutting-edge spatial mapping technology, the Zamani Project team will continue to work towards their vision of a society in which current and future generations have access to, and protect, African and international cultural heritage.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.