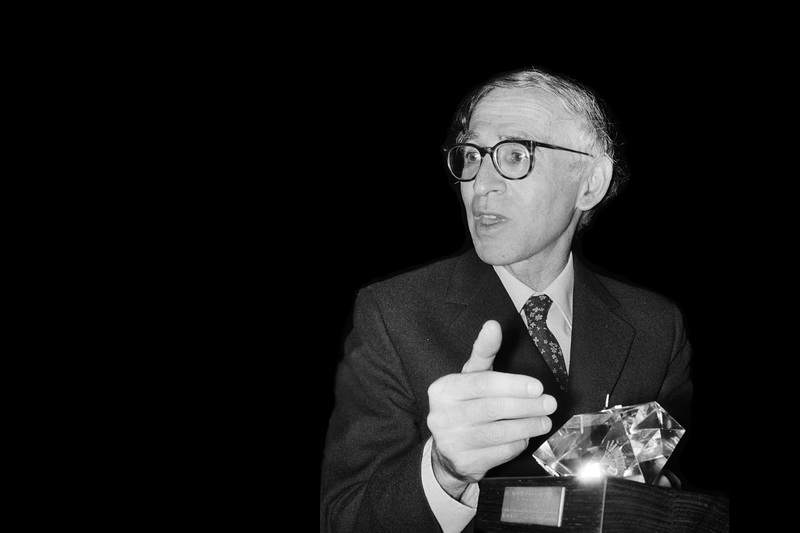

‘Razor-sharp intellect, exceptional humility’

12 December 2018 | Story Supplied. Photo Supplied. Read time 5 min.

University of Cape Town (UCT) alumnus and a founding trustee of the UCT Trust, Nobel Prize winner Sir Aaron Klug, is remembered for his “razor-sharp intellect”, yet “exceptional humility”.

Paying tribute to the former student and lecturer, who died on 20 November, aged 92, Institute of Infectious Disease and Molecular Medicine director Professor Valerie Mizrahi recalled that his “razor-sharp” intellect “literally radiated from every fibre of his being”.

Besides that, she said she most remembered being struck by Klug’s “exceptional humility”.

“I have subsequently heard many others making the same observation. This quality, more than any other, is what I will remember most about [him].”

Klug, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1982 for his invention of three-dimensional electron microscopy, and his work in charting the complex structures of chromosomes, maintained close ties with UCT after his stint at the university, first as a student and then as a lecturer.

After earning his master’s in physics at UCT, he stayed on as a lecturer and worked on the X-ray analysis of some small organic compounds. It was in fact during this time that he developed “a strong interest … in the structure of matter, and how it was organised”, he later wrote in his Nobel biography.

Founding trustee

Although Klug then moved to the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge University to pursue his PhD, and later to Birkbeck College in London, he was a frequent visitor to Cape Town where he lectured at UCT and gave generously of his time in the Department of Biochemistry.

He was one of the founding trustees of the UCT Trust, which he chaired from 1993 to 2010. During his time in office, the Trust raised more than £17 million for university projects.

He received four awards from UCT, namely the President of Convocation Medal, the Chancellor’s Gold Medal of Merit (1982), an honorary doctorate (1997) and the Vice-Chancellor’s Medal (2010).

In 1988, Klug was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II, and between 1995 and 2000 he served as president of the Royal Society, the world’s oldest independent scientific academy. Closer to home, former President Thabo Mbeki awarded Klug the Order of Mapungubwe (Gold) in 2005.

Offering her condolences to Klug’s family and friends on behalf of the university, Vice-Chancellor Professor Mamokgethi Phakeng said UCT is proud to call Klug “one of our own”.

“He is a great example of the kind of graduates that [UCT] strives to produce.”

She lauded his immense contribution to the university over the years via his role at the UCT Trust, saying the Trust continues to reap the benefits today of his hard work and robust loyalty.

“He is a great example of the kind of graduates that our university strives to produce,” Phakeng said, referring to Klug’s achievements as “phenomenal”.

During his PhD studies in Cambridge, Klug successfully modelled the austenite-pearlite phase transitions in steel using EDSAC, one of the world’s first computers. He developed the nucleation and growth model that has been applied in many systems.

He won a Nuffield Fellowship in 1953, which led to a chance meeting with X-ray crystallographer Rosalind Franklin, who introduced Klug to the study of viruses. In particular, he determined the helical symmetry of the tobacco mosaic virus and progressed towards the determination of the three-dimensional structure of spherical viruses by electron microscopy.

Discovery of zinc-finger proteins

Following 1959, his work on spherical viruses led to the realisation that the images of viruses being obtained with the electron microscope were projections that contained information about the whole three-dimensional structure. His work later proved critical to the inventors of the X-ray computed tomography (CT) scanner.

The work for which Klug will ultimately be remembered is his discovery of zinc-finger proteins, a class of proteins that bind specific DNA sequences. The modular nature of these proteins enabled the design of synthetic proteins that opened the way to the prospect of targeted therapies for a wide range of diseases.

Professor Bryan Sewell, of UCT’s Department of Integrative Biomedical Sciences, said of Klug that he symbolises “what every scientist strives for – brilliant insight, the combination and reconciliation of theory and experiment, and the wide-ranging application of ideas to many fields”.

Klug is survived by his wife Liebe and son David. His other son, Adam, died in 2000.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.