Commissions of inquiry vs courts of law

08 November 2018 | Story Cathleen Powell. Photo Presidency of South Africa. Read time 6 min.

South Africans might be forgiven for expecting two key commissions of inquiry currently underway to change the country. Some of these expectations, however, are unrealistic, as a look at the commissions’ functions and powers show.

Some expectations might be met, but only if the commissions achieve public buy-in and generate enough pressure for change.

Whether they can do that depends not only on their powers but also on how they are run.

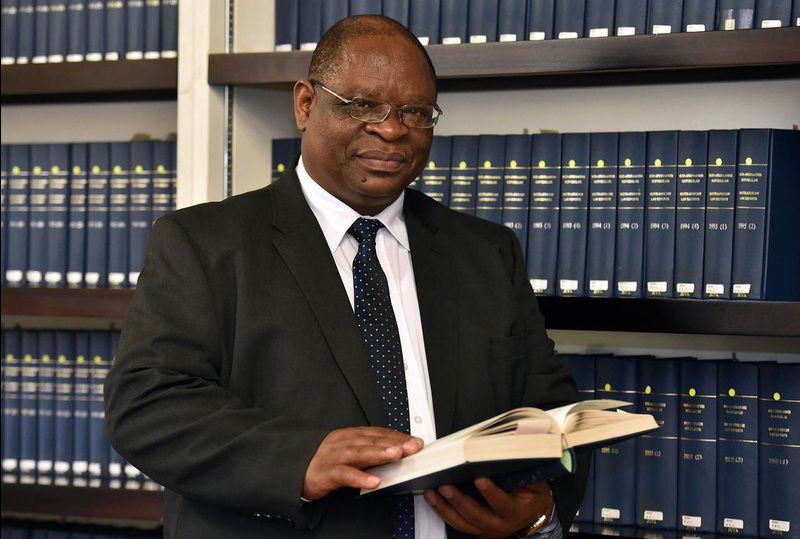

The probe into tax administration and governance at the South African Revenue Service – headed by Judge R Nugent – and has already led to the axing of Tom Moyane as head of the tax collection agency. The other inquiry – headed by Deputy Chief Justice Zondo – is looking into allegations that the South African state has been captured by private business interests allied to former President Jacob Zuma. It’s expected to run for two years.

Unrealistic expectations about what commissions can achieve comes from the fact that they’re often confused with courts of law. This isn’t surprising given that they seem to function like courts. For example, they’re often chaired by judges, affected parties are often represented by lawyers and witnesses take oaths to tell the truth.

But they aren’t courts. And it’s important to understand the difference between the two when it comes to their functions, powers, and procedures.

The differences

A court judgment is binding and has direct legal effect on the parties involved. The court will determine that the accused goes to prison, for example, or that the defendant pays damages. The only way affected parties can escape the court order is by getting it overturned on appeal or review by a higher court.

Commissions of inquiry, on the other hand, make non-binding recommendations to the person who set them up. (In the case of these two commissions, that’s President Cyril Ramaphosa.) Technically, all commissions do is offer the person who set them up advice. And they’re required to stick to the issues on which advice was requested. These are set out in the terms of reference which establish what questions the commission must answer, who will head it up and what its powers are.

Commissions of inquiry are completely different from courts when it comes to procedures too.

South Africans courts are adversarial. The judge sits as an outside observer while the two teams before her attempt to establish their version of events. Commissions of inquiry, on the other hand, are inquisitorial. This makes the commission the driver of the investigation itself. It seeks out the facts rather than waiting for two opposing parties to choose and present their evidence. In an inquisitorial process, the witnesses and their lawyers are merely assisting the commission’s investigation.

An important consequence of the inquisitorial process is that a commission is not bound by the same rules of evidence as in a court. Thus evidence will never be “inadmissible”, as the commission enjoys discretion to consider all evidence that it finds relevant to its inquiry.

Why the confusion

With these important distinctions in mind, why have some commissions become “judicialised” and lawyer-driven? Why was the first day of the Zondo Commission taken up with technicalities? Why have postponements been built into the process so that “implicated parties” can study the allegations made against them?

It’s not just to stave off the threat of a court challenge to any findings. Such a threat is, in fact, not much of a threat at all. Commissions of inquiry will not be subject to the (higher) standards of so-called “administrative” review unless their findings have a direct effect on the persons who might want to challenge them. But the direct effect would arise only when the president acts on the findings.

The president wouldn’t be subject to administrative review in many of these cases either. Instead, the president and the commission will be subject to review for “rationality”. A rationality review asks only whether there is a rational connection between the conduct challenged before the court and a legitimate governmental objective.

But commissions have another, equally crucial function – to educate the public and ensuring its buy-in for important processes of change and renewal.

South Africans are already incensed at the loss of public funds to corruption, the devastation of public institutions at the hands of those who sought to profit by it, the damage this has caused to the country’s economy and the suffering it has inflicted on the poorest in society.

But all South Africans have to be on board with the solution to the problem. This sort of buy-in is possible only if the facts are widely known, the relevant law is clear, and the commission investigating the problem is accessible to the public and is seen as legitimate.

A commission can achieve this by having open hearings, broadcast publicly, public access (such as a website and an enquiry desk) and a strong, independent commissioner.

This is where the judicial procedure comes in. Although it can render the body less accessible, it does have the strong advantage of satisfying people’s innate sense of natural justice.

And the decisions of the commissions will only have legitimacy in the eyes of the public if they are seen to treat people fairly. That is one of the reasons why implicated people need enough time to respond to the allegations against them.

The value of the commissions

The Nugent Commission is due to report soon while the Zondo Commission may take two years.

The long delay between the advent of a crisis and a commission’s report is often used as an argument that they’re being used to put matters “on hold”.

However, commissions of inquiry don’t remove an issue from the public eye if they’re run openly and transparently. Instead, they draw the public in to the issue, educating and inviting engagement. The most important work of the Zondo and Nugent Commissions might be done before their formal function – the submission of their reports – is completed.![]()

Cathleen Powell, Associate Professor in Public Law, University of Cape Town.