How ancient humans survived a volcanic winter

05 April 2018 | Story Ambre Nicolson Photos Various Read time 7 min.

An international team, including UCT researchers, have shown that ancient humans living on the coast of South Africa not only survived, but thrived, during the eruption of a super volcano and the ensuing volcanic winter it caused.

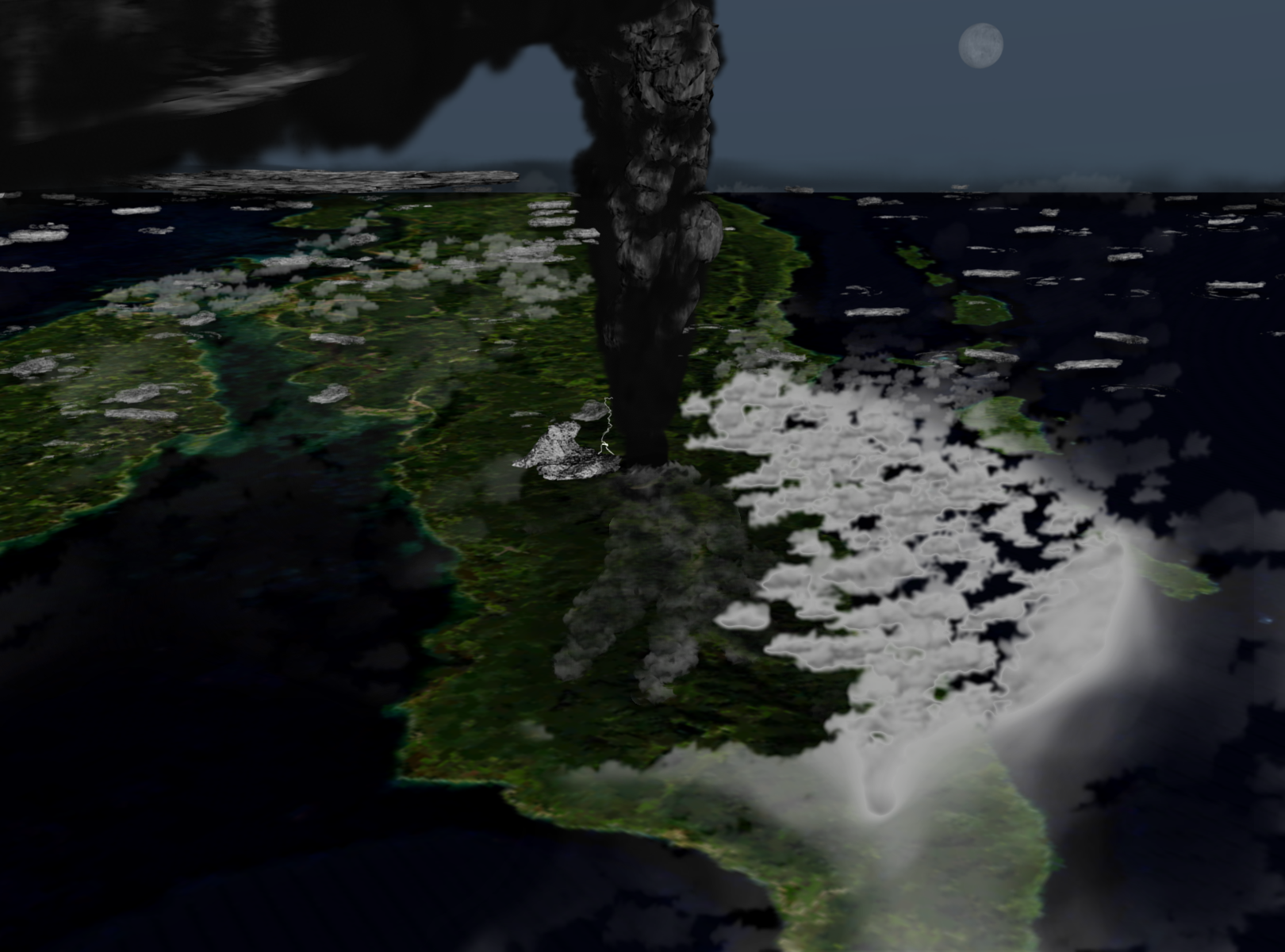

Mount Toba is the largest eruption to occur on Earth during the past two million years. When the super volcano erupted 74 000 years ago on what is now Sumatra, it spewed 4 000 cubic kilometres of smoke and ash into the atmosphere in just a few days. This huge cloud of dust and sulphur had a cooling effect on the Earth’s atmosphere, causing temperatures to plummet and the planet to plunge into a winter that lasted for many years.

In the past, scientists believed that the effects of this eruption explained the steep fall in human numbers right around the time that humans were emerging from Africa.

Now, an international group of researchers – including Dr Jayne Wilkins, an archaeologist in the Department of Archaeology at UCT – who recently published their findings in the journal Nature, have found that early human populations on the coast of South Africa not only survived the immediate aftermath of the eruption, but in fact thrived through the volcanic winter that followed.

What is a volcanic winter?

When a super volcano erupts, it spews ash, glass and gasses into the atmosphere. One of the gasses it releases is sulphur dioxide. When this enters the atmosphere in high volumes, it can form aerosols that reflect the sun’s rays. This in turn causes a reverse-greenhouse effect in which temperatures fall and plants can no longer photosynthesise due to the lack of sunlight. The result is a crash of entire ecosystems.

If you were a human being living in certain parts of the world at the time, you would experience an endless winter with dwindling plant and land-based animal life. Little wonder then that in the 1990s a prominent anthropologist, Professor Stanley Ambrose at the University of Illinois, hypothesised that this volcanic winter might explain the ‘bottleneck’ that occurred in human populations at the time.

New evidence: cryptotephra, human evolution and seafood

In 2011, Arizona State University archaeologist Curtis Marean showed Gene Smith, a geologist from the University of Nevada, a soil sample taken from an area close to two archaeological sites on the coast of South Africa: Vleesbaai and Pinnacle Point 5-6. Smith identified layers of volcanic ash in the soil sample.

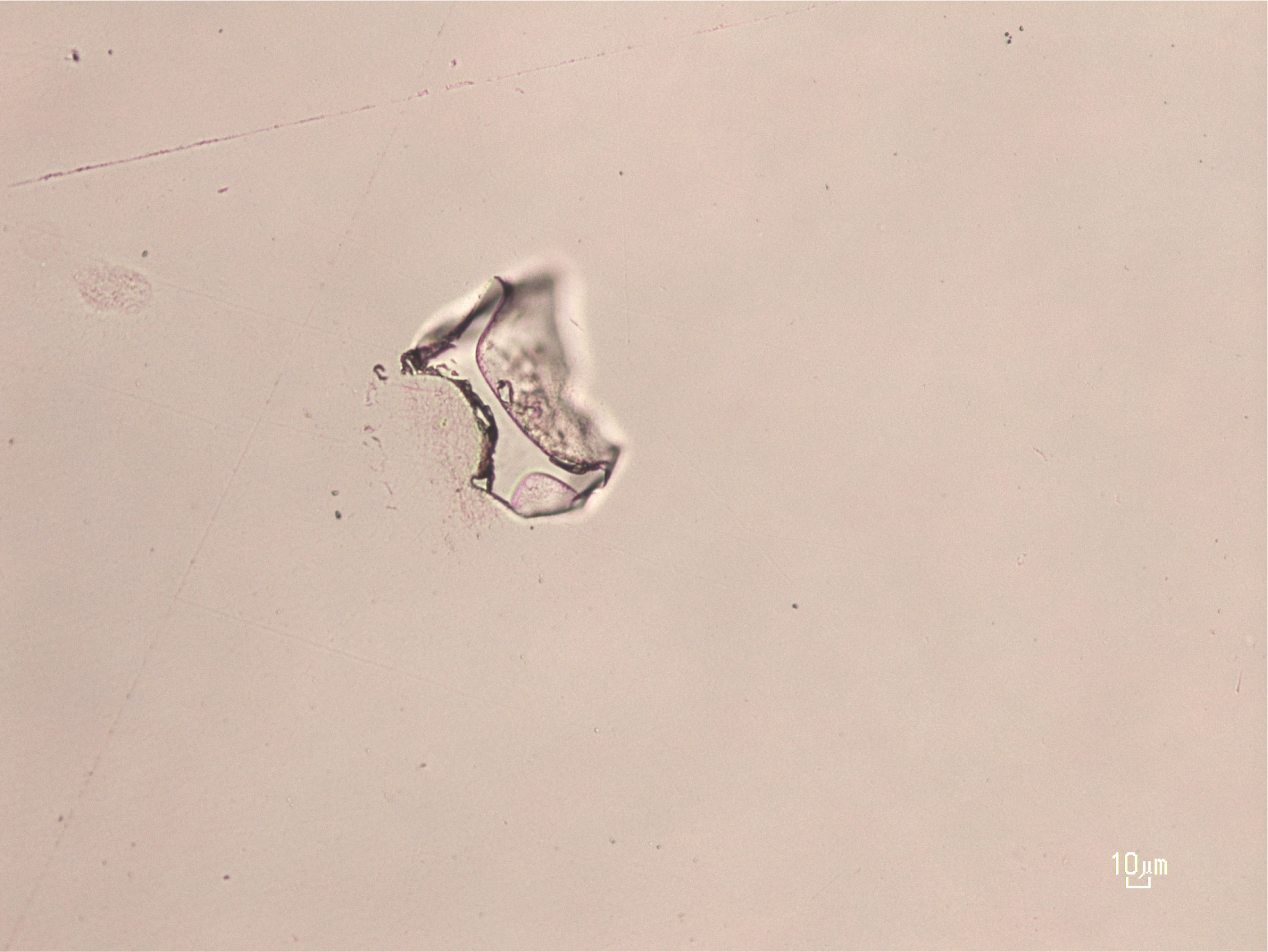

The first task for researchers was to identify which eruption caused the layer of ash. They did this by finding cryptotephra at the sites. These microscopic glass fragments of volcanic rock can be linked chemically to the eruption – in this case, Toba – that caused them. Having discovered cryptotephra at the site, researchers examined the signs of human settlement, such as heat-treated stone tools, animal bones, shellfish and evidence of fires. To their surprise they found over 400 000 artefacts above, below and among the layers of ash containing the cryptothephra.

Indonesia and was found, recently, at an archaeological site in Vleesbaai,

South Africa, nearly 9 000 kilometres away. Photo by Racheal Johnsen.

“This was a big surprise for us,” explains Wilkins, who led the archaeological dig at one of the two Middle Stone Age sites where the cryptotephra was recovered. “Especially when we discovered that cryptotephra was present in the sediments at Vleesbaai. Vleesbaai is an open-air site, which means it’s not protected by rock shelter walls. These kinds of sites out on the landscape usually have poorer preservation.”

The nature and number of artefacts found showed that, not only did human populations living in South Africa survive the eruption, but that their numbers may have grown. “Our research shows that early humans were resilient in the face of environmental change and puts to bed an old hypothesis about the impact of the Toba super-eruption on human evolution,” explains Wilkins.

But that is not the only reason their discoveries are significant. “The research also presents a brand new method for dating archaeological sites based on the presence of the cryptotephra that can be chemically matched to particular eruptions,” says Wilkins. “It’s a big deal to find a new method that can help to link up the archaeological records between sites.”

Scientists are now theorising that one of the reasons that human beings survived in that particular area is the reliance of these populations on a diet of fish and shellfish, animals which would not have been as badly affected by the prevailing atmospheric conditions. According to Wilkins, it is not yet clear whether this site on the South African coastline represents the only refuge for surviving humans during this time or whether other such sites might exist.

“It is up to archaeologists now to try and find more sites, like the ones on our coastline, that show that early humans may have thrived elsewhere in Africa,” she says.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.