What remains is memory

07 July 2017 | Story Kate-Lyn Moore.

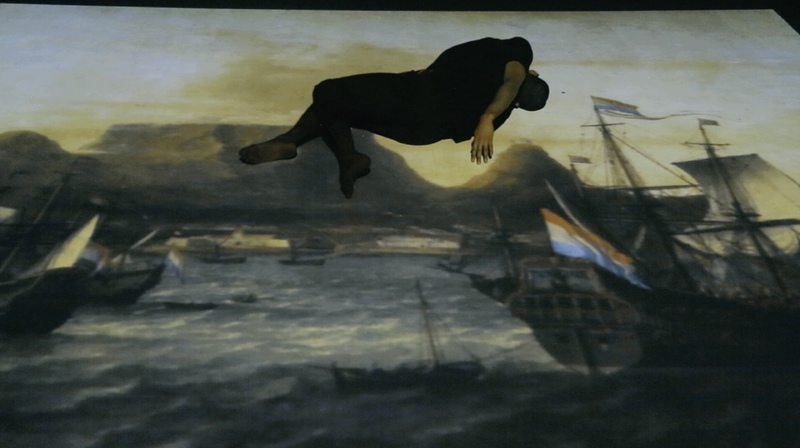

Celebrated author and playwright Dr Nadia Davids is staging her latest piece, What Remains, in Cape Town this month.

Born out of the discovery of a mass burial site in Prestwich Place, Green Point, What Remains deals with unaddressed histories and collective memory. Davids speaks to Kate-Lyn Moore from the UCT newsroom.

You are a prolific writer, but are also trained in theatre. This is something that you focused on in your PhD at UCT. How do you see this coming forward in your work?

There is a role that theatre plays in South African literature that is incredibly important. One of the components of that is that it allows us to ask questions about what constitutes a text. So in literature, in novels, the text is the thing. But in theatre the text is only one component of what is eventually written. Bodies inscribe their own meaning within a performance…

I think what is quite special and beautiful about what happens in theatre is that it enacts its own disappearance. So when one is talking about the relationship between theatre and memory, there is kind of a psychic interface between those two states.

Memory is sort of untraceable. Theatre is performed live. When something is live it disappears when done, then it exists only in the memory of the audience members who have gone to see it.

So I think with a play like this, which is dealing in some ways with the idea of memory, of disappeared memory, of forgotten memory, of what happens when landscapes hold memories even if they are not necessarily spoken into being, and also of collective memories ... in that way theatre is kind of uniquely positioned to answer some of those questions.

Could you tell me about the four characters in What Remains: The Healer, The Archaeologist, The Dancer and The Student?

I had been working at the District Six Museum at the time the bones were discovered, but I didn’t pay them as much attention as I might have, even though everyone around me was thinking about these things very deeply.

It was really only when I went back a decade later and started looking at the research and at what this moment actually meant that it struck me as astonishing and remarkable, a kind of prophecy, really, of what was to come in the city.

There was a development site for a luxury apartment block, and within the first week of breaking ground there was this discovery of this mass-burial grave of, I think there were up to 3 000 bodies that were exhumed: babies who were six-weeks old, to men in their late 60s. And the vast majority of them were slaves.

This eruption of these bones to the surface generated this cacophony of different responses: from archaeologists and heritage managers who wanted to prioritise the scientific examination of the bones, because there was incredibly important information to be drawn from them; property developers wanting to keep going; and an alliance of community activists who claimed descendancy from these bones, desperately wanting them to be reinterred and given a proper burial, and feeling that to re-examine these bones would be to once again commit violence on them.

It occurred to me that this is an extraordinarily South African moment: that people could look at one thing and see it so differently, and have different priorities about it and have different value systems about how they approach it.

It struck me that this is kind of an argument between embodied cultural memory and historical scientific practices. So I wanted to write a piece that was thinking about some of those things, but to make it both of, and not of, Cape Town. So that is why I haven’t given a specific place in which it’s happening.

The play works with the idea of archetypes and in the original draft, The Student was actually the narrator, somebody who was watching and observing this thing unfolding.

It was under Jay [Pather]’s direction, when we did the first incarnation of the play, that we asked Ameera Conrad, who was our stage manager, to come in to read the narration. Based on how she and Jay worked, it became clear that this actually wasn’t a narrator, this was a student. It became about: what is The Student’s response to this thing that is happening?

The Dancer doesn’t have text, but we decided very early that we wanted to have a figure who was beyond text, who could narrate stories through movement and dance.

The Healer for me is one of these figures that are both of the world and not of the world. She is kind of an ancient prophetess, but she is very practical and sensible at the same time. The Healer is the one who knows the minute the bones are unleashed, she is the one who is up all night talking to the ghosts and trying to calm them down.

So in some ways the breaking ground and the disturbance of these bones becomes a metaphor for something else, for an unaddressed history and what happens when you don’t address a history.

I think it was [UCT lecturer] Julian [Jonker] who described Prestwich Place and District Six as unfinished business in the city. And South Africa is unfinished business.

This play is incredibly well timed, given the discussions that have been taking place in the city.

It’s a really tough city. It can be equal parts extraordinary and confounding. And it’s an erasing place as well. I think that extraordinary juxtaposition between extreme beauty and shocking inequality is so disorientating.

I was doing up my writer’s notes the other day and I was saying, the thing about Cape Town is that it allowed for a kind of protected unknowingness. It is possible to be of and from this place and not have to engage with its histories. It is possible to live in that way until the past erupts and demands one’s attention.

When you don’t live somewhere, you just don’t have the same sense, the same feeling for the currents and the contradictions in what’s happening.

So when I wrote the piece and sent it to Jay, it was Jay who was much more alert to why the text was significant at this time. I didn’t really understand that. And sometimes those kinds of things happen, you write something and you are not fully cognisant of why it’s going to connect to a certain moment. But it was Jay who understood that. It was him who said, we must do this now because it is absolutely of now.

What Remains runs at Hiddingh Hall from 6 to 12 July at 20:00 daily, with selected matinees.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.