Media postgraduates’ sprint through data to tackle spatial inequality

13 June 2017 | Story Carla Bernardo. Photo Johnny Miller.

Quick and dirty are not usually adjectives you want to associate with your research. But it has proven an apt description for the work of – and deliberate tactic by – postgraduates investigating the media’s role in tackling spatial inequality in Cape Town.

In a first for the Centre for Film and Media Studies (CFMS), this year’s cohort of postgraduates embarked on what is known as a data sprint, presenting their initial findings to their peers and others barely a month after they first started their investigation.

As with previous years, the postgraduates self-selected their research methodology electives, choosing between content analysis, qualitative research and social media analysis.

However, what makes this year’s work different is that they combined forces to tackle the overarching question, “Spatial inequality in Cape Town: exploring the media’s role”.

This combination of expertise aimed at resolving one research question within the relatively short time frame, and with a public approach, is known as a data sprint.

“In a short space of time, people with different areas of speciality combine forces to produce a quick and dirty research result,” says Associate Professor in Media Studies and Production Tanja Bosch.

Bosch, who drove the idea for a data sprint and the public presentation of the findings, wanted to challenge the perception that research is conducted from an ivory tower.

Through the data sprint, researchers interact with the communities under investigation, encouraging them to conduct research that will make a difference.

It also provides researchers with an overview of the field, lessening the likelihood of tunnel vision. And, while findings of a data sprint will inevitably have gaps, there is an opportunity to refine the necessary aspects of the research afterwards.

Why spatial inequality?

With the methodology chosen, a research question was needed.

Twenty-three years into democracy, the remnants of racial segregation remain, the number of people able to afford life in the city centre has decreased, and no social housing has been built in the city centre since 1994. It was the perfect topic – current, trending, and with the opportunity to make a difference.

While discussions around spatial inequality have been ongoing, the topic began grabbing headlines soon after the launch of Reclaim the City (RTC).

The campaign, launched in February 2016, was in response to gentrification, spatial inequality and the use of public land for profit. It became a platform for evictees and activists for affordable and suitable housing, as well as a dominant voice in local media.

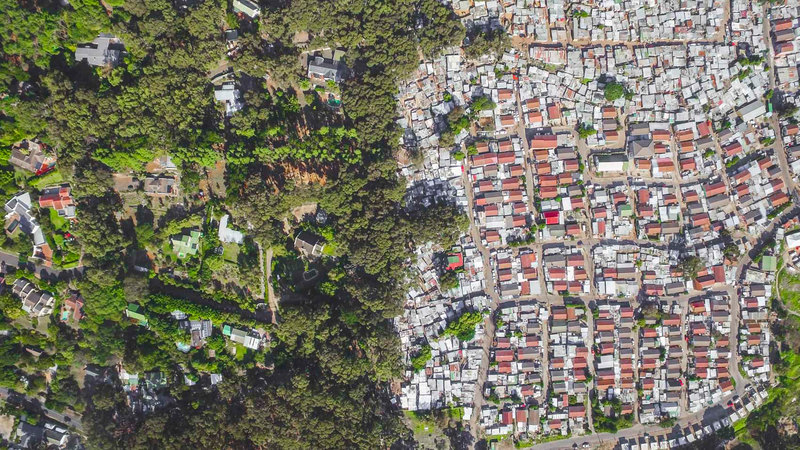

Similarly, the work of UCT alumnus Johnny Miller received global recognition, fuelling further conversation about spatial inequality. Miller’s drone photography juxtaposes neighbouring low- and high-income areas, illustrating the vast physical differences.

With ample content on hand, postgraduates were given the task of exploring and reporting on the media’s role in shaping public perceptions.

So, what have been the initial findings?

Men and elites get the airtime

The first group conducted a content analysis data sprint, answering the umbrella question, “How do South African newspapers frame spatial inequality in Cape Town?”

Among their findings was that spatial inequality is indeed a hot topic, specifically in Cape Town. Media coverage was primarily events-driven and was typically in favour of RTC rather than property developers and the City of Cape Town.

The media also tend to give more airtime to men and to so-called “elites”, such as civil society organisations and government officials. Interestingly, the group found that very few articles appeared in the Afrikaans press and, where they did, there was no direct voice used nor interviews conducted with people on the street.

Spatial inequality or service delivery

The second group used qualitative research to answer the question, “How do activists perceive the role of the media in shaping perceptions of spatial inequality?”

Through their interviews with activists, the second group found that RTC actively targeted media, using the sale of the Tafelberg site to build a campaign around spatial inequality. They found that media had been an effective tool in this regard.

They also found that spatial inequality stories were often framed as service delivery protests by the media, and that journalists were frequently unable to access affected locals who feared victimisation.

Is social media an effective tool?

The third group investigated the social media ecology of spatial inequality in Cape Town. This group began with the view that social media enabled ordinary South Africans to participate in the spatial inequality discussion while also providing a space for activists to make visible their struggles and mobilise individuals.

The group looked at the three main social media networks – Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. They found that the three accounts leading the discussion on spatial inequality were RTC, Ndifuna Ukwazi (NU) and Future Cape Town, whom they collectively termed “key actors”.

Their findings included that social media was used to raise awareness, place issues on the public agenda and choreograph protest action.

The way forward

With initial findings in hand, the groups will now take into account the feedback of their peers and RTC.

However, activist groups such as RTC can already draw on the research, including considering the distribution of Afrikaans press releases and opening up of their social media conversations to the public.

Daneel Knoetze, the NU communications officer who also provides mainstream and social media support for RTC, welcomed the research. As is the case with similar campaigns, success often relies on public discourse and “new, persistent and solution orientated discussions”.

“In fostering and sustaining such discussions, we know that platforms of mass media, specifically traditional and social media, play a significant role. But questions of how to best utilise these platforms often go unanswered,” he says.

He adds that the groups’ research would assist in better understanding the role of the media in advancing the demand for a desegregated Cape Town.

“We're looking forward to applying the findings in practice.”

Once those results are submitted, the groups will present their findings at the country’s only media studies conference, the South African Communication Association.

Thereafter, Bosch hopes for interdisciplinary collaboration within the university, tackling one problem.

“That would be turning the university into a real learning space with real public scholarship. That would be like a dream.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.