Time to see TB patients as true champions in the fight against the disease

31 March 2017 | Story Paul Mason and Anna Coussens

Nearly 70 years ago, a range of antibiotics that could treat tuberculosis were first identified. But today almost two million people still die every year from one of the deadliest infectious diseases. That’s about 5000 people every day. In the face of this tragedy, the ever increasing rise in drug resistant tuberculosis adds to the concern of clinicians and scientists at the front line of TB care and prevention worldwide.

South Africa, as well as having the world’s highest rates of TB, also has the highest rate of HIV associated TB, and one of the largest outbreaks of extremely drug resistant (XDR)-TB. The most likely explanation for the emergence of these bacteria is inadequate or incomplete treatment.

Blame has been pointed at patient (mis)behaviour, funding shortfalls, and technological shortcomings. But it’s time to challenge this dogma. We have ignored that the patient is a victim of poor community prevention programmes that wrongly stigmatise those suffering from the disease. Patients are now more likely to catch drug resistant TB than they are likely to develop resistance by not taking their drugs.

TB patients in low-income settings overcome incredible obstacles in completing their full treatment course. They need to be treated as the true champions in our fight against TB, rather than victims of stigmatisation.

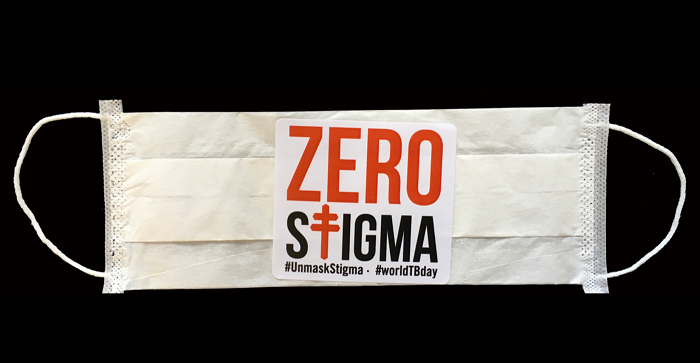

New initiatives to reach out to people whose lives have been affected by TB are needed to reduce the stigmatisation. And communities need to be empowered to recognise and actively challenge their circumstance. The World Health Organisation has recognised this which is why it launched the ZERO Stigma campaign on World TB day this year.

Clinicians are increasingly finding cases of drug resistant TB and have even been forced to diagnose cases of “totally drug resistant TB” when patients living with TB have become unresponsive to all known antimicrobials.

Standard therapy for TB requires a specially devised combination of antimicrobials. The courses are lengthy. Strains of tuberculosis that are not effectively killed by a standard drug regimen are said to be drug resistant.

People with drug resistant TB bacteria are placed on treatment for at least two years, over which time they receive more than 20,000 pills and 200 injections.

They have a high likelihood of going deaf as a side effect of the drugs and ultimately only have a 30% chance of survival.

Drug resistant TB is increasingly becoming transmitted, rather than acquired. This means that the problem of drug resistance is not merely clinical, but dramatically epidemiological.

In other words, it’s a public health problem. More than that, living in a globalised world where infectious diseases easily cross borders means that TB is a global health problem that none of us should ignore.

For example, a project which tracked 400 XDR-TB patients living in South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal Province found that between 60% and 80% of these patients had not developed the disease because they were not diligently observing their daily treatment routine of injections and pills.

They caught the bacteria from someone else coughing in their vicinity. This means there aren’t sufficient safety measures to prevent others from also getting infected.

Which is why the social and cultural contexts of TB matter.

More outreach campaigns are needed. Public engagement in TB control is limited which is why it outranks infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS where a cure is unavailable but community support has been strong.

If we don’t adequately support the patients to complete appropriate treatment to stop the transmission of TB, then diagnostic shortfalls, treatment shortcomings, and resistance to future drugs will continue to occur.

Laboratory experimentation and clinical research needs to be matched with qualitative studies into the social, economic and political dimensions of TB, with a voice given to people living with this disease.

The current drug resistance problem is caused by diagnostic services, prescribed therapies and public health systems failing the patient, not the patient who fails therapy.

TB drug resistance will not be defeated with novel antibiotic discoveries and new diagnostic technologies alone.

Social and cultural measures have to be considered in the equation too.

Story by Paul Mason, Lecturer in Anthropology, Monash University, Monash University and Anna Coussens, Senior Lecturer in Medical Microbiology, University of Cape Town.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

This article first appeared in The Conversation, a collaboration between editors and academics to provide informed news analysis and commentary. Its content is free to read and republish under Creative Commons; media who would like to republish this article should do so directly from its appearance on The Conversation, using the button in the right-hand column of the webpage. UCT academics who would like to write for The Conversation should register with them; you are also welcome to find out more from carolyn.newton@uct.ac.za.

South Africa, as well as having the world’s highest rates of TB, also has the highest rate of HIV associated TB, and one of the largest outbreaks of extremely drug resistant (XDR)-TB. The most likely explanation for the emergence of these bacteria is inadequate or incomplete treatment.

Blame has been pointed at patient (mis)behaviour, funding shortfalls, and technological shortcomings. But it’s time to challenge this dogma. We have ignored that the patient is a victim of poor community prevention programmes that wrongly stigmatise those suffering from the disease. Patients are now more likely to catch drug resistant TB than they are likely to develop resistance by not taking their drugs.

TB patients in low-income settings overcome incredible obstacles in completing their full treatment course. They need to be treated as the true champions in our fight against TB, rather than victims of stigmatisation.

New initiatives to reach out to people whose lives have been affected by TB are needed to reduce the stigmatisation. And communities need to be empowered to recognise and actively challenge their circumstance. The World Health Organisation has recognised this which is why it launched the ZERO Stigma campaign on World TB day this year.

20 000 pills and 200 injections

Clinicians are increasingly finding cases of drug resistant TB and have even been forced to diagnose cases of “totally drug resistant TB” when patients living with TB have become unresponsive to all known antimicrobials.

Standard therapy for TB requires a specially devised combination of antimicrobials. The courses are lengthy. Strains of tuberculosis that are not effectively killed by a standard drug regimen are said to be drug resistant.

People with drug resistant TB bacteria are placed on treatment for at least two years, over which time they receive more than 20,000 pills and 200 injections.

They have a high likelihood of going deaf as a side effect of the drugs and ultimately only have a 30% chance of survival.

Drug resistant TB is increasingly becoming transmitted, rather than acquired. This means that the problem of drug resistance is not merely clinical, but dramatically epidemiological.

In other words, it’s a public health problem. More than that, living in a globalised world where infectious diseases easily cross borders means that TB is a global health problem that none of us should ignore.

For example, a project which tracked 400 XDR-TB patients living in South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal Province found that between 60% and 80% of these patients had not developed the disease because they were not diligently observing their daily treatment routine of injections and pills.

They caught the bacteria from someone else coughing in their vicinity. This means there aren’t sufficient safety measures to prevent others from also getting infected.

Which is why the social and cultural contexts of TB matter.

Mobilising Communities to #UnMaskStigma

More outreach campaigns are needed. Public engagement in TB control is limited which is why it outranks infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS where a cure is unavailable but community support has been strong.

If we don’t adequately support the patients to complete appropriate treatment to stop the transmission of TB, then diagnostic shortfalls, treatment shortcomings, and resistance to future drugs will continue to occur.

Laboratory experimentation and clinical research needs to be matched with qualitative studies into the social, economic and political dimensions of TB, with a voice given to people living with this disease.

The current drug resistance problem is caused by diagnostic services, prescribed therapies and public health systems failing the patient, not the patient who fails therapy.

TB drug resistance will not be defeated with novel antibiotic discoveries and new diagnostic technologies alone.

Social and cultural measures have to be considered in the equation too.

Story by Paul Mason, Lecturer in Anthropology, Monash University, Monash University and Anna Coussens, Senior Lecturer in Medical Microbiology, University of Cape Town.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

This article first appeared in The Conversation, a collaboration between editors and academics to provide informed news analysis and commentary. Its content is free to read and republish under Creative Commons; media who would like to republish this article should do so directly from its appearance on The Conversation, using the button in the right-hand column of the webpage. UCT academics who would like to write for The Conversation should register with them; you are also welcome to find out more from carolyn.newton@uct.ac.za.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Related

Why South Africa's carbon tax should stay

24 Feb 2026

Republished

Cape Town’s wildflowers: six key insights from a new checklist

19 Feb 2026

Republished