'A teacher all her life'

17 February 2017 | Story Helen Swingler.

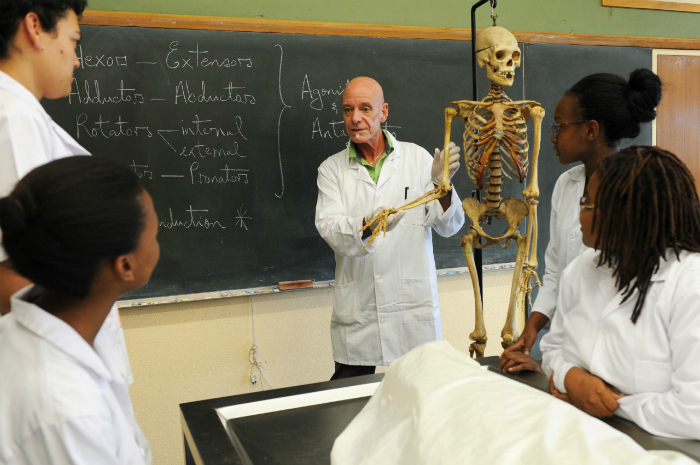

Beneath the surface we are as individual as our faces. It's a fact many second-year health sciences students are startled to learn when they first put scalpel to skin on the cadavers in the anatomy laboratories.

For human anatomy lecturer Professor Graham Louw, who oversees the Faculty of Health Sciences' annual ceremony to honour body donors and the bodies of indigent people, this speaks to the range of human variation.

The amount of fat; the differences in the sizes, shapes and positions of organs; the usual ageing of the body; sexual dimorphism, based on hormonal influences; and muscular symmetry (or lack thereof) and vascular supply of the limbs are peculiar to each individual.

“And as the students open up the bodies, the medical history of the individual is revealed as the students see signs of pathology, previous surgical interventions, and present and past diseases,” said Louw.

Anatomy is not always what the textbooks, apps, models and aids show, said Professor Malcolm Collins, head of the Department of Human Biology.

“Nothing matches the hands-on dissection, layer by layer and organ by organ, of a once-live being,” he told the gathering at last week's annual ceremony to honour those who'd donated their bodies to the Faculty of Health Sciences and to thank their families for supporting their decisions.

These donors are vitally important 'silent' teachers.

Walter and Oomie

The student-driven ceremony honoured everyone in dance, music, poetry or reflection. Some students spoke movingly of their experiences in the anatomy laboratory.

One group called their cadaver Walter after a professor in their favourite TV series; another gave their cadaver a more generic name, Oomie, an affectionate title bestowed on an elder.

Names are important.

“I tried to forget who he was before he came [here],” said student Yaaseen Gallant of his group's cadaver. “But he had a likeness to my grandfather … Maybe his big heart was a sign of his life, the depth of his love … In his own way, he taught me to cherish all the little things that make my day.

“As we closed him up for the last time, peace on his face was all I could see. It was the last time that I would attend his lecture; the last lesson that he would teach me.”

Student and cellist Rendert Hoekstra performing a lamentation. Photo Robyn Walker.

Student and cellist Rendert Hoekstra performing a lamentation. Photo Robyn Walker.

MSc (Med) candidate Kyle Paulssen, now in his second year of MBChB, had studied anatomy but said he'd never prepared himself for whole-body dissection.

“It was different seeing the manicured nails, the tattoos, the scars, which almost always shocked me and reminded you that the body you were dissecting was a person with a history, loved ones, friends and a whole life you know nothing about.”

He hopes this training will ultimately help in the identification of those that are victims of crime, “unclaimed and left in the fields to become bones”.

“I volunteered as a member of the UCT-based forensic pathology services on forensic cases in helping find the identities of discovered remains and finding out more about how and why they died. This is vital in helping provide some closure to families or missing persons.”

But Paulssen also found an unlikely connection.

“He [Oomie] had the same scar I had from a similar operation, which immediately gave me a special bond with him, bringing the anatomy to life in death … It's not only the development of knowledge for improved treatment for the live patient; it's taught me that care does not stop when a patient dies. It's taught me to empathise with those you know nothing about.”

Indictment on society

But the cadavers are not all donors. At a past ceremony the department's Dr Charles Slater, a senior lecturer in anatomy, noted that one of the first cadavers to be dissected at UCT's fledgling anatomy department at the South African College (the university's forerunner) in 1911 was the body of a 29-year-old. He'd been hanged for the murder of a merchant hatter in Rosebank.

Though Roeland Street Gaol was close to the Hiddingh Campus, which housed the medical school, there seem to be no other incidences of prisoners being used for dissection at UCT, he said.

The bodies of the indigent and unclaimed are not bequeathed to the Faculty of Health Sciences but come via the Department of Health. Louw hopes that the annual ceremony honours especially those who lost their identities – society's most vulnerable.

Because of student protests and a truncated academic year in 2016, last week's ceremony was the first in two years. Among the rolling list of donors' names (2015 to 2017) one stands out: Lucky Emergency. Here's a story that begs telling. But if the donor was indigent or unclaimed, the book is closed.

Student Rouxlé Schmeisser depicting the life cycle in dance. Photo Robyn Walker.

Student Rouxlé Schmeisser depicting the life cycle in dance. Photo Robyn Walker.

Identities erased

Student Maya Pillay said that the phenomenon of indigent and unclaimed bodies was an indictment on society.

“I was really happy that an event like this was organised because knowing that there would be family members here to talk about the people that donated their bodies, there is a chance to restore an identity to at least some of those bodies.”

But when it came to indigent 'donors', her concern was that “certain bodies are being erased; certain bodies are being remembered more than others”.

There are no indigent donors, she noted.

“These bodies were not donated, were not given. They were simply taken. These were the bodies of some of the most vulnerable people in our society. Because no loved one claimed them from the Department of Health, they slipped through a tunnel of paperwork into the hands of the medical school.

“In life, these people had no adequate support structures, no permanent homes. They were very poor; some of them suffered from severe illnesses that killed them young. Many of them likely also struggled with mental-health problems. And they are inevitably, overwhelmingly, the bodies of people of colour.

“These are people who never gave consent to having their bodies used in this way, who did not find freedom even in death. Their consent did not matter because in life their minds, their desires, their decisions, their consciousnesses were not valued by a neoliberal, anti-poor, so called post-apartheid state.

“So let them be not as erased in death as they were in life. Let us mourn them, too. Let them be human beings too.”

Her poem reflected movingly on her experiences and relationship with the female cadaver her group dissected. Here is an excerpt of the spoken version of her poem, titled “the cause of death was cryptococcal meningitis”

vi. in Tupperware I find you,

in clothes-hangers your ribcage,

in orange-peel the folds of your brain.

when I try to tell my doctor

that I may be seeing ghosts

your fingers fill my mouth

and, reaching down into my chest

you say: “There's nothing in here

at all, is there?”

there was a city in you, once,

but now it's just us pigeons,

picking through what's left

after that long and terrible night.

vii. I look at the body

And you, tongueless in life, eyeless now,

Look back at me.

Devoid of being, the void of being

Is where you have left me.

Later, when the lab is empty,

I lean close to your ear and whisper:

If I could bring you back, I would.

The next day, I think we are on better terms.

while the others skin your thighs

I reattach your jawbone, adorned with its last remaining tooth, black to the bone, and

ask you: What comes afterwards?

You say:

There are no cities here.

vii. I cut into the body

and the body cuts into me

and I'm leaking out

into my gloves.

there's something in here,

I say,

be careful.

The Faculty of Health Sciences held its annual memorial and thanksgiving ceremony to honour the cadavers used in dissection. These are both from donors and indigent people. Photo Robyn Walker.

The Faculty of Health Sciences held its annual memorial and thanksgiving ceremony to honour the cadavers used in dissection. These are both from donors and indigent people. Photo Robyn Walker.

After the student presentations, donors' families and friends were invited to share their thoughts.

A woman whose mother had donated her body said, “She was a teacher all her life. When we finally told my daughters and sons granny was coming to the medical school, they said, 'Well mom, granny taught us so many things all her life; isn't it wonderful that she's carrying on teaching?' ”

If you'd like to donate your body to science, download information about UCT's body donation programme, as well as the body donor consent form.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.