Remembering SS Mendi

13 February 2017 | Story by Newsroom

Remembering the Mendi goes well beyond commemorating a maritime tragedy 100 years ago that claimed the lives of over 600 black South African volunteers on their way to serve king and country in the First World War.

Forty metres beneath the surface of the English Channel, the century-old wreck of the SS Mendi is disintegrating under the forces of nature, corrosion, currents and age. Memory, however, has proved hardier; time has not eroded the wreckage of its history, the monumental scale of its meaning.

The Mendi represents not simply the cost of war – the bald facts of a collision at sea – but the multiple, complex costs of 20th-century South Africa's history.

In late January 1917, the doomed 600 bedded down for the last time on South African soil at the Rosebank Showgrounds – now UCT's lower campus, where one of many Mendi memorials stands. The men would have been transfixed by what lay ahead: the adventure, sights unimagined and the nearing, daunting war.

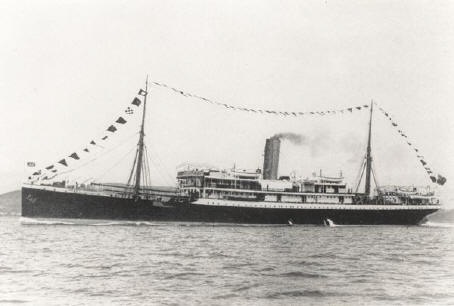

But when the 4 200-ton Mendi sailed from Table Bay for the North Atlantic on 25 January, there must also have been a sense among the 5th battalion of the South African Native Labour Contingent (SANLC) that, whatever they privately felt about empire or king, their voluntary service must surely prove their worth as citizens.

This was of more than idle concern: just three years earlier – on top of the 1910 Union deal between whites, denying most blacks the franchise – the 1913 Land Act had cut their land ownership to just 7.3% of the country, impelling them towards the compounds and 'locations' of industrial wage labour.

Would war service not corroborate their claims to equity?

Playing their part

The Union government had been reluctant to send black South Africans to the European theatre at all, expressly in case they got ideas about claiming political equality.

However, in 1916, when London sought the empire's help in relieving fighting men of labouring duties, the Union had a change of heart – but only as long as black South Africans were unarmed; billeted apart; limited to menial tasks such as loading, digging, sawing and hauling; and kept under the thumb of white officers.

Despite reservations – South African Native National Congress general secretary Sol Plaatje recognised that “it seems to have occurred to the authorities that the best course is to engage the natives in a capacity in which their participation will demand no recognition” – much of the black elite backed the labour contingent recruiting drive.

If the response was patchy, the fact is, by the war's end, 21 000 black South Africans had played their part in the 300 000-strong labour corps that was drawn from Africa, the Middle East, Asia and the Caribbean.

So, in late January, the Mendi sailed for Le Havre, via Plymouth.

The sinking of the Mendi

Returning from dropping off Nigerian troops in East Africa early in 1917, the Mendi docked in Cape Town to pick up the 5th – and last – 800-strong SANLC battalion and their twenty-two white officers.

The ship reached Plymouth on 19 February, leaving for France the next afternoon under escort by the destroyer HMS Brisk.

Thick fog settled over the calm icy waters of the channel in the early hours of 21 February as the Mendi, at reduced speed, nosed its way gingerly towards the French coast.

Shortly after 04:45, another vessel was heard approaching, but evasive action proved futile. The 11 000-ton SS Darro, sailing at full speed, struck the Mendi, leaving a deep gash in its starboard side. The two ships drifted apart, and the Mendi, rapidly filling with water, sank in just 20 minutes.

As the ship listed, and men slid off the deck, some lifeboats couldn't be launched, and many of the battalion ended up in the icy water.

An outrage for which the captain of the Darro was later penalised was the larger vessel's failure to help in the rescue. There were only 267 survivors, a few drifting on life rafts for two or three days before being saved.

Most of the dead (607 black troops, 9 white officers and some 30 crew) were never recovered. A few bodies later floated ashore, hence the isolated Mendi graves at Portsmouth, Hastings, Littlehampton, Wimereux in France, and Wassenaar and Bergen op Zoom in Holland.

While the Mendi was not the only labour corps transport to be lost at sea, in the total of South Africa's war dead of 9 500, the disaster was the second worst single loss after the attrition of Delville Wood six months earlier.

But its symbolic potency exceeds the scale of facts.

Honouring the dead

The Mendi Memorial on UCT's lower campus created by artist Madi Phala on the site of the tented barracks where the Mendi dead spent their last night on South African soil. Photo Michael Hammond.

The Mendi Memorial on UCT's lower campus created by artist Madi Phala on the site of the tented barracks where the Mendi dead spent their last night on South African soil. Photo Michael Hammond.

When news of the calamity reached South Africa, the fact of Prime Minister Louis Botha and the entire House of Assembly rising in silent respect on 9 March was unprecedented – a token of regard seemingly reinforced only months later when King George V told SANLC ranks at Abbeville: “You are also part of my great armies fighting for the liberty and freedom of my subjects of all races and creeds throughout the empire.”

But not, it turned out, liberty and freedom for black South Africans.

If official indifference and amnesia only grew in the long years of white supremacy, the catastrophe remained vivid in black social and political consciousness – a key agent of the resurgent interest in the vessel and its symbolism today.

The wreck site, first located in 1945 – and subjected to a rigorous ongoing archaeological survey by Wessex Archaeology in 2006 – was declared a protected war grave in 2009.

Democratic South Africa has honoured the Mendi men in the naming of one of the country's highest awards for bravery, and of two navy vessels, the frigate SAS Mendi – which laid a wreath in 2004 where its namesake went down – and the missile boat SAS Isaac Dyobha.

This last name is especially meaningful.

Perhaps the most enduring memorial is the legend of Chaplain Isaac Williams Wauchope Dyobha's rallying speech on the sinking Mendi and the death drill that followed.

“Be quiet and calm, my countrymen,” Dyobha urged, “for what is taking place is exactly what you came to do. ... Brothers, we are drilling the death drill. I, a Xhosa, say you are my brothers. Swazis, Pondos, Basutos, we die like brothers. We are the sons of Africa. Raise your war cries, brothers, for though they made us leave our assegais in the kraal, our voices are left with our bodies.”

There is no evidence from survivors' accounts of the death drill, or of Dyobha's speech, yet it has become central to understanding the indelible meaning of the tragedy – the fraternal bond, the willing sacrifice, the claim to history.

UCT's memorial events

On 26 February the Gunners Association, Western Province, will host a military parade and memorial service as part of the centenary commemoration of the sinking of the SS Mendi, at which UCT will be represented by Acting Vice-Chancellor, Professor Francis Petersen. This will take place at the lower campus Mendi Memorial, created by artist Madi Phala in 2006.

On the same day “Abantu beMendi” will open at the Centre for African Studies Gallery. The exhibition features commissioned artworks on the Mendi and the South African Native Labour Contingent by artist Buhlebezwe Siwani, Mandla Mbothwe and Hilary Graham; poetry, including SEK Mqhayi's “Ukutshona kukaMendi”; and rare photographs and documents, including the tonic sol-fa “Ama-gora e-Mendi” by AM Jonas. The exhibition will also include footage of the ceremony at sea over the wreck site for the descendants of the Mendi troops.

From 28 to 30 March, the Centre for African Studies will recognise the role that the people of the Mendi played in a broader struggle for land, human rights and dignity in a multidisciplinary conference, “Ukutshona kukaMendi”/ “Ukuzika kukaMendi”, featuring local and international scholars, poets, film-makers, artists and performance artists. Fred Khumalo's new novel about the Mendi, Dancing the Death Drill, will be launched at the conference.

Story Michael Morris.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.