Victoria Mxenge: A homeless people's struggle for dignity

21 November 2016 | Story by Newsroom

Associate Professor Salma Ismail's book about the Victoria Mxenge Housing Project shows how “poor, vulnerable women who were semi-literate, from rural areas, who had settled on the outskirts of the city, gave a desolate piece of land life and built sustainable communities”.

The Victoria Mxenge Housing Project (VM), born in Philippi on the outskirts of Cape Town, achieved great success as an affiliate of the South African Homeless People's Federation (SAHPF), which was supported by the People's Dialogue (PD), building more than 5 000 homes between 1992 and the early 2000s. The homes were of markedly better quality than the Reconstruction and Development Programme houses, says Ismail, who teaches in UCT's Department of Adult Education. But VM built more than just houses, she adds: they built communities.

Ismail's book The Victoria Mxenge Housing Project was published in 2015 and shares the evolution of a people's housing movement in post-apartheid South Africa. With their massive early success – and the support from the state – VM was a poster child for what was possible in South Africa's new democracy.

Assoc Prof Salma Ismail holds up a copy at the book's launch in 2015.

Assoc Prof Salma Ismail holds up a copy at the book's launch in 2015.

In 2002 SAHPF and PD formed the South African Alliance and partnered with the state to provide housing on a larger scale. PD provided proxy subsidies on behalf of the state to speed up the process, but the state did not honour its obligations and PD was bankrupted, says Ismail.

Things started to go wrong in the early 2000s. In a whirlwind of acronyms, the SAHPF split, VM remained with the original federation and a breakaway group formed the Federation of the Urban Poor (FEDUP).

“[FEDUP] have actually now formed more of a liaison with Lindiwe Sisulu, who is the housing minister,” says Ismail. “So they are actually closer to the state now than the SAHPF. Power shifts all the time. But that's too complicated for the book.”

Has this had a material impact?

“They [VM] get fewer contracts because the state has basically made everybody a contractor.”

But the contracts have been going to FEDUP, say the VM women.

Anne Harley, writing in Adult Education Quarterly, notes that the SAHPF was a “manufactured, vanguardist social movement”. Read alongside Professor Linda Cooper's description of PD as “led mainly by white, middle-class development activists”, and of VM as veteran ANC Women's League members who sought critical engagement with the state rather than mobilising against it, the context in which more radical housing rights groups such as Abahlali baseMjondolo formed becomes clear.

Poking patriarchy in the eye

While political niggles muddied the water, perhaps inevitably, VM demonstrated what was possible in the microcosm of the post-patriarchal world they created.

They were mainly a women's organisation – only five members were men – and this was not accidental.

“The reason they give for being a women's organisation only is they say men like power and violence,” explains Ismail. “They also had the experience of Crossroads, where there was the time of evictions in Crossroads, when the men negotiated separately with the state and actually agreed to the removals.”

“They also say that as women they look after the house; they are there when the evictions take place; they are there when there's a fire. Also, they are the ones who see to the food. They say they're doing this for their children. That's why they are very clear about wanting this to be a women's organisation.”

But People's Dialogue also targeted them as women, arguing that women pay back the loans, she adds.

VM's experience in Crossroads made them acutely aware of male power in an organisation.

The state split the Crossroads community during the period of forced evictions, says Ismail. It was a very patriarchal community, she argues, so some of the men were happy to go behind the women's backs and strike a covert deal with the state.

Masakhane

VM was born in the era of Masakhane: coined by then-president Nelson Mandela, it's the spirit of taking the initiative, or self-help.

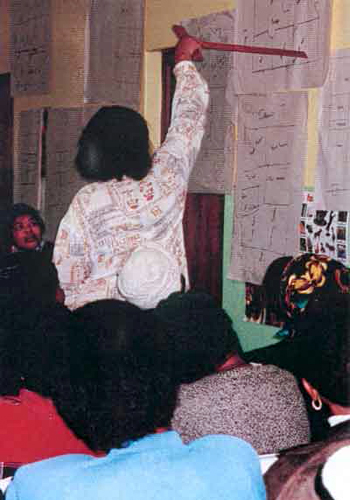

The Victoria Mxenge builders share their housing plans.

The Victoria Mxenge builders share their housing plans.

“Masakhane is about people taking responsibility for their own upliftment and participating in the governing of their own lives,” the late statesman told a 1998 rally in Bothaville.

In starting the savings scheme that would become the Victoria Mxenge Housing Project, the women learnt an array of hard and soft skills.

“[They gained] knowledge about building, drafting a plan, costing a plan …”

Education was a key driver for VM, says Ismail. Patricia Matolengwe, one of the movement's founders, was known for her motto “Ufundu zufes”, which means “we learn until we die”.

In addition to learning how to build houses, the VM women also learnt soft skills about their own empowerment, building their own confidence, negotiating with experts in the housing environment, in government – “and most of the people they negotiated with were men,” she says.

Sticking to their slogan of building communities, Ismail says that one indeed feels a sense of community when spending time in the Victoria Mxenge community.

“If you visit a community housing [project] that's just been built by contractors, it has a completely different feel. People have come from all over and settled there.

“It's very different to a space when a whole community builds a community, struggled for it, built it together and supported each other, you know?”

They built in a team, says Ismail. When one person got a subsidy, the community helped that person build their home.

The first houses at Victoria Mxenge.

The first houses at Victoria Mxenge.

New frontiers needed

With the political melee to negotiate, VM found niche markets like providing houses for disabled people and for pensioners.

The book doesn't delve too deeply into VM's work after the split, but the last chapter does look at how they've since become more critical of the state.

“If you're getting social goods from the state, you're not going to be so critical,” observes Ismail.

VM prioritised education in their programme – they built a crèche and are developing a youth education programme – but the fallout showed that education alone is not enough for justice and social rights to prevail.

“You need the support of the state. The state didn't realise its social goal. When the state changed from the RDP to GEAR [Growth, Employment and Redistribution], it changed its development [plan].”

The state still issues a housing subsidy, but the upper limit of a R3 500 monthly income has not been adjusted for inflation and higher living costs, says Ismail.

“It hasn't realised that people earn more [but] that doesn't mean that they can afford housing,” she says. “The state has not taken that into account.”

The state has not shared SAHPF's vision; in fact, Ismail says that the ineffective state has fragmented the housing movement and betrayed its promises to the poor.

Story Yusuf Omar. Photos Supplied.

Read related items:

- The Victoria Mxenge Housing Project

Released: 12 September 2016 - Sisters are building it for themselves

Released: 16 February 2015

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.