Why a narrow view of restorative justice blunts its impact

17 November 2016 | Story Sarah Malotane Henkeman

We have all at one time or another applied the principles and practices that restorative justice is based on. These are intuitively drawn on to resolve conflicts between couples, parents and children, extended families, friends, neighbours and colleagues.

South Africa’s Department of Justice states that the “resurfacing of Restorative Justice Philosophy may be foreign to Roman Dutch Law but it has been part of the African indigenous justice system”. In “Restorative Justice: a road to healing” it says that, instead of viewing crime as an act against the state,

Mediation between victims and offenders is conducted by trained lay and professional people within and beyond the criminal justice system.

The principles and practices on which modern forms of restorative justice are based have deep roots in indigenous and religious approaches to social harm.

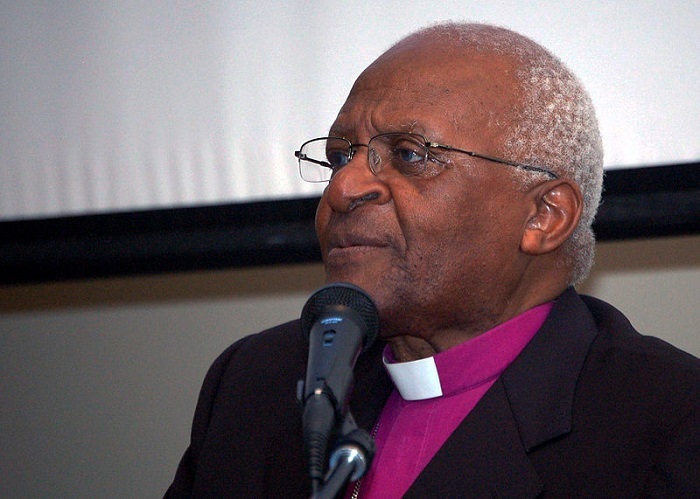

South Africa’s Emeritus Archbishop Tutu says that,

Restorative justice is used across the world. This includes countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, North America, the Caribbean and the Pacific.

It has produced uneven results. In South Africa, the best-known example of restorative justice was the country’s qausi-judicial Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). This has been criticised for placing racial reconciliation before economic reconciliation.

As a society South Africa has allowed the focus on relationships to obscure the role that historical and growing inequality plays in sabotaging these relationships.

Some researchers who focus on the intra- and interpersonal levels of restorative justice see it as effective. But “unorthodox” researchers and scholars (including my own trans-disciplinary work) make the case for a more expansive approach. This goes beyond an individual-level criminal justice lens to include social and economic structures that co-produce harms in society.

Theoretically, restorative justice is understood to be part of social justice and peacebuilding at the societal level. But practical application of the approach is often limited to the micro, individual level.

For example, current restorative justice processes are limited to individual wrongdoing. They focus on the restoration of relationships between victims and offenders.

The problem with this approach is that it does not focus on the causes and consequences of wrongdoing. These are rooted in inequality, particularly in societies where this has been embedded over generations. This leaves structural causes of harm and injustice intact.

For example, the Khulumani support group was initiated by victims who testified at the TRC. The support group has a growing membership in excess of 100,000. The limitations of individual-level responses are illustrated on a T-shirt worn by a survivor on their website, which reads:

Modern forms of restorative justice attempt to “rehabilitate” offenders and “reintegrate” them into a broken social system. Alternatively, attempts are made to “fix” the individual to make him or her more resilient, sober or responsible.

This leaves the cumulative psychological and material impact of injustices such as colonialism and apartheid untouched.

Modest applications of restorative justice are therefore inadequate. They do not challenge persistent structural inequality. They also obscure society’s role in perpetuating violence by relying on the criminal law definition of crime. This holds individuals solely responsible.

On the other hand, expansive applications of restorative justice have the flexibility to take into account the interaction of individual and societal factors that co-produce violence.

This is why unorthodox restorative justice scholars like Gregg Barak argue for a more expansive approach in which both society and individuals are healed.

Recent research shows that mediation practitioners need special training. This is to ensure that they sharpen their ability to identify patterns in their knowledge about the society they live in. They also learn to recognise new instances of these patterns in the narratives of others.

If practitioners are trained to “see”, “hear” and “articulate” deeper and broader patterns in the cases they mediate, they can help make different forms of violence “visible”. In turn this can raise the awareness and consciousness of society, add to the body of academic knowledge and inform policy.

Adopting this approach would also produce knowledge that could inform education literature for “structurally responsive” restorative justice training. This would be based on information sharing and awareness-raising as well as education and action to build critical consciousness.

As psychologist Helena Neves Almeida suggests, practitioners can extend and deepen the effect of their work when they identify “recurring conflict between similar types of social actors”. They can then approach these conflicts

If violent contexts are not taken into account, restorative justice does not serve broader society. Instead it serves as a peacemaking process within a paradigm stacked against the poor and vulnerable. They feel emotionally lighter, but remain structurally trapped after the process is completed.

A move to more social justice-driven peacebuilding practice will yield more data for analysis, and more accurate policies, strategies, techniques and tactics. They will also resonate at every level of society.

By Sarah Malotane Henkeman, Independent conflict and social justice practitioner/researcher. Currently senior staff associate in the Faculty of Law, University of Cape Town. Image by Cmdr. JA Surette, US Navy, Wikimedia.

South Africa’s Department of Justice states that the “resurfacing of Restorative Justice Philosophy may be foreign to Roman Dutch Law but it has been part of the African indigenous justice system”. In “Restorative Justice: a road to healing” it says that, instead of viewing crime as an act against the state,

restorative justice sees crime as an act against the victim and shifts the focus to repairing the harm that has been committed against the victim and community. It believes that the offender also needs assistance and seeks to identify what needs to change to prevent future re-offending.

Mediation between victims and offenders is conducted by trained lay and professional people within and beyond the criminal justice system.

The principles and practices on which modern forms of restorative justice are based have deep roots in indigenous and religious approaches to social harm.

South Africa’s Emeritus Archbishop Tutu says that,

restorative justice is characteristic of traditional African jurisprudence that is infused with ‘the spirit of ubuntu’, which seeks to restore, heal or mend breaches, imbalances and broken relationships.

Restorative justice is used across the world. This includes countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, North America, the Caribbean and the Pacific.

It has produced uneven results. In South Africa, the best-known example of restorative justice was the country’s qausi-judicial Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). This has been criticised for placing racial reconciliation before economic reconciliation.

As a society South Africa has allowed the focus on relationships to obscure the role that historical and growing inequality plays in sabotaging these relationships.

Some researchers who focus on the intra- and interpersonal levels of restorative justice see it as effective. But “unorthodox” researchers and scholars (including my own trans-disciplinary work) make the case for a more expansive approach. This goes beyond an individual-level criminal justice lens to include social and economic structures that co-produce harms in society.

Limits to restorative justice

Theoretically, restorative justice is understood to be part of social justice and peacebuilding at the societal level. But practical application of the approach is often limited to the micro, individual level.

For example, current restorative justice processes are limited to individual wrongdoing. They focus on the restoration of relationships between victims and offenders.

The problem with this approach is that it does not focus on the causes and consequences of wrongdoing. These are rooted in inequality, particularly in societies where this has been embedded over generations. This leaves structural causes of harm and injustice intact.

For example, the Khulumani support group was initiated by victims who testified at the TRC. The support group has a growing membership in excess of 100,000. The limitations of individual-level responses are illustrated on a T-shirt worn by a survivor on their website, which reads:

No reconciliation without truth, reparation and redress.

Modern forms of restorative justice attempt to “rehabilitate” offenders and “reintegrate” them into a broken social system. Alternatively, attempts are made to “fix” the individual to make him or her more resilient, sober or responsible.

This leaves the cumulative psychological and material impact of injustices such as colonialism and apartheid untouched.

Modest applications of restorative justice are therefore inadequate. They do not challenge persistent structural inequality. They also obscure society’s role in perpetuating violence by relying on the criminal law definition of crime. This holds individuals solely responsible.

On the other hand, expansive applications of restorative justice have the flexibility to take into account the interaction of individual and societal factors that co-produce violence.

This is why unorthodox restorative justice scholars like Gregg Barak argue for a more expansive approach in which both society and individuals are healed.

A broader definition

Recent research shows that mediation practitioners need special training. This is to ensure that they sharpen their ability to identify patterns in their knowledge about the society they live in. They also learn to recognise new instances of these patterns in the narratives of others.

If practitioners are trained to “see”, “hear” and “articulate” deeper and broader patterns in the cases they mediate, they can help make different forms of violence “visible”. In turn this can raise the awareness and consciousness of society, add to the body of academic knowledge and inform policy.

Adopting this approach would also produce knowledge that could inform education literature for “structurally responsive” restorative justice training. This would be based on information sharing and awareness-raising as well as education and action to build critical consciousness.

As psychologist Helena Neves Almeida suggests, practitioners can extend and deepen the effect of their work when they identify “recurring conflict between similar types of social actors”. They can then approach these conflicts

in their structure and not just in their individuality.

If violent contexts are not taken into account, restorative justice does not serve broader society. Instead it serves as a peacemaking process within a paradigm stacked against the poor and vulnerable. They feel emotionally lighter, but remain structurally trapped after the process is completed.

A move to more social justice-driven peacebuilding practice will yield more data for analysis, and more accurate policies, strategies, techniques and tactics. They will also resonate at every level of society.

By Sarah Malotane Henkeman, Independent conflict and social justice practitioner/researcher. Currently senior staff associate in the Faculty of Law, University of Cape Town. Image by Cmdr. JA Surette, US Navy, Wikimedia.

This article first appeared in The Conversation, a collaboration between editors and academics to provide informed news analysis and commentary. Its content is free to read and republish under Creative Commons; media who would like to republish this article should do so directly from its appearance on The Conversation, using the button in the right-hand column of the webpage. UCT academics who would like to write for The Conversation should register with them; you are also welcome to find out more from carolyn.newton@uct.ac.za.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Related

Why South Africa's carbon tax should stay

24 Feb 2026

Republished

Cape Town’s wildflowers: six key insights from a new checklist

19 Feb 2026

Republished