Future of SA water looks brighter

16 September 2016 | Story by Newsroom

South Africa is experiencing its worst drought in a century.

Amid grim predictions of global water scarcity and world water wars, the University of Cape Town (UCT) has launched the Future Water research institute.

Future Water holds to a positive stance: that water scarcity can and must be addressed using science, technology, innovative thinking and an understanding of the human factor.

In a display of unexampled interdisciplinarity, the team has put forward a plan that is supported by strong sociological, technical, environmental, legislative and governance expertise.

Introducing the centre at its launch on 8 September 2016, Vice-Chancellor Dr Max Price explained how the institute encompasses the skills and resources of ten different departments across six faculties, while maintaining an open call to other researchers and academics.

Traditionally, chemical engineers think about water reprocessing; civil engineers consider water treatment, warehousing and distribution; sociologists and anthropologists look at human behaviour and how this may need to change; and scientists consider the environmental impact.

In the new paradigm, the Future Water team will integrate their knowledge to find integrated, acceptable and sustainable solutions for our water challenges – ranging from personal water use to agricultural, industrial and mining use.

All the while, the economic, legal and policy considerations of this valuable public resource, such as pricing, will be superimposed.

“The ability to bring this together is one of the unique features that a university can offer,” Price said.

Research-driven policy

Professor Sue Harrison, director of Future Water, greets Minister Nomvula Mokonyane of the National Department of Water Affairs and Sanitation at the launch of Future Water. Photo Candice Mazzolini.

Professor Sue Harrison, director of Future Water, greets Minister Nomvula Mokonyane of the National Department of Water Affairs and Sanitation at the launch of Future Water. Photo Candice Mazzolini.

The launch of Future Water was attended by government officials, NGO members, industrialists and academics. Both the minister of Water Affairs and Sanitation, Nomvula Mokonyane, and the director general of the Department of Science and Technology, Dr Phil Mjwara, addressed the need for research to inform policy work.

The institute aims to address water sources, governance and policy, and modes of use within its four planned areas of cross-cutting research.

Professor Sue Harrison of the Department of Chemical Engineering, and director of Future Water, outlined the following thematic areas: New taps (new water resources), Blue-green infrastructure (water sensitive management), Adapting to change (building resilience/governance) and Maximising value (maximising value from minimum resources).

Through these approaches, the Future Water team hopes to expand existing water resources, encourage water sensitivity and efficiency, maximise the productivity of resources, and address health and nutrition through technological solutions, sociological perspectives and governance.

Intricately linked as it is to food, energy, human and environmental health, economic development and political instability, water is the top long-term global risk, Harrison explains.

Demonstrating global trends in water supply and demand over a 25-year period, Harrison indicated that sub-Saharan Africa's demand for water is predicted to increase by 283% over the next 25 years. The water supply however, will remain more or less constant unless innovative new sources are tapped into.

New ways of thinking

Such evidence makes it clear that new ways of thinking and acting are required to address the water crisis.

As Mokonyane noted: “We have relied on surface water and have not explored any other source of water for water security in South Africa.”

This exploration should include storm-water and rain-water harvesting, treating waste water and desalinating water.

“Blue-green infrastructure looks at attaining sustainability through an integrated approach and adaptive response to meet future water needs,” explained Harrison, “and it deals with health, economic value, planning and design, ecosystem services, food security and social development in the way that they all need to interact with each other to achieve this through water-sensitive design.”

Such ventures need to be supported by a resilient system that is governed by appropriate laws and policies that take cultural understandings of water into account. Relating directly to how we use it in our lives, this impacts water demand directly.

“Precisely because everybody assumes water is free – that, on its own, requires behavioural change,” noted Mokonyane. “As a nation we have, over time, ignored the importance of treating water as a scarce commodity.”

“The final theme, Maximising value, is [concerned with] closing the loop around waste management and the product life, for greater reuse, recycling and repurposing,” said Harrison.

“It's around resource efficiency. It's around circular economy, and it's around the industrial ecology in which one person's waste is another person's raw materials.”

Inspiring a new generation

A range of projects, both current and planned, will bring together work that is already being done at the university.

One such project, called The Water Hub, seeks to bring innovation and development together in order to inspire a new generation to do water work.

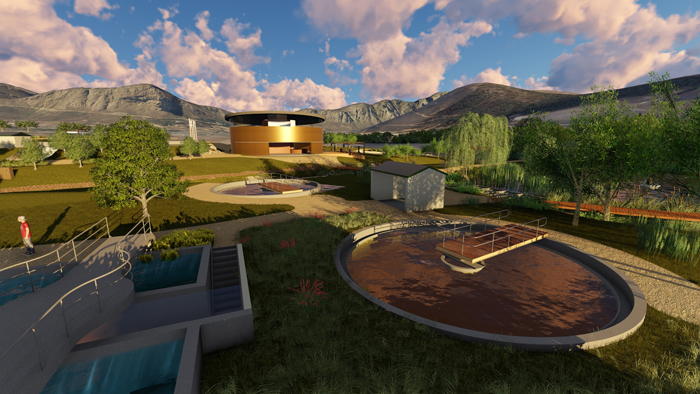

The project is based at the abandoned water treatment facility in Franschhoek, which lies along the banks of the contaminated Stiebeul River.

Dr Kevin Winter of the Department of Environmental and Geographic Sciences presented an almost idyllic scene at the Future Water launch, where the best of nature's many restorative processes are critically combined with new ways of reimagining the sciences.

The Water Hub aims to combine the expertise of students and researchers across multiple disciplines to address issues surrounding water, energy and food.

Completely off the grid in terms of energy and sanitation, The Water Hub will test and showcase a range of sustainable water-management processes to treat polluted run-off and improve the quality of the Stiebeul River, grow its own food sources and experiment with ecological housing, among other things.

In a move to be both environmentally and financially sustainable, the plan is to establish The Water Hub as an attractive conference venue, complete with its own restaurant to support the costs of this state-of-the-art interdisciplinary research centre.

A focus on interdisciplinarity

The Future Water Institute was launched on 8 September. It is an exciting venture that aims to address the critical issue of water scarcity in South Africa. Photo Candice Mazzolini.

The Future Water Institute was launched on 8 September. It is an exciting venture that aims to address the critical issue of water scarcity in South Africa. Photo Candice Mazzolini.

Recognising the importance of the interdisciplinary approach in tackling a number of South Africa's current challenges, UCT has set out to nurture its interdisciplinary research. The Future Water research institute was one of the five winning proposals that responded to the university-wide call.

Future Water is built on UCT's substantial research footprint in water and the many kinds of work that are being done on water. The institute was established to allow a much greater impact of this water-focused research to be realised, producing something greater than the sum of its parts.

Story Kate-Lyn Moore.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.