Same-sex marriage – assimilation or radicalisation?

15 September 2016 | Story by Newsroom

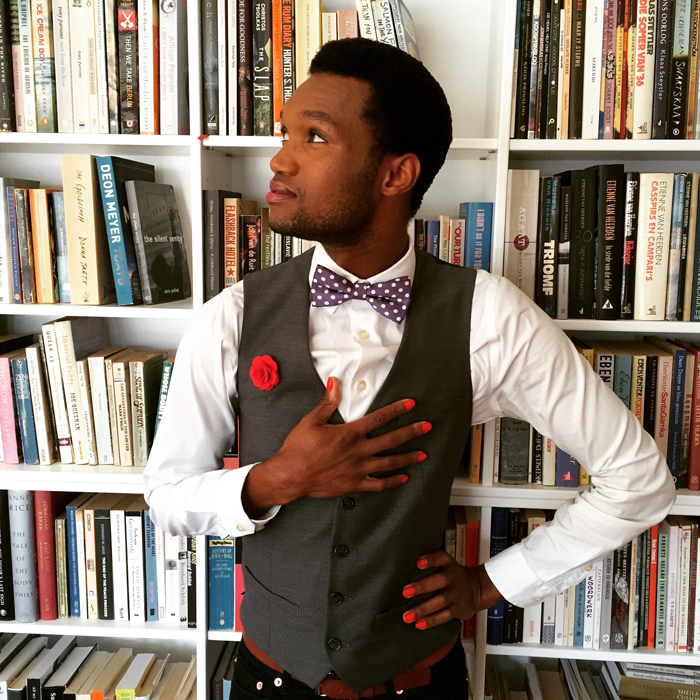

Ten years after South Africa legalised marriage between same-sex couples, UCT sociology student Lwando Scott is on the cusp of finishing a doctorate that explores how the experiences and challenges of same-sex couples speak to the democratic and decolonisation projects.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, two academics sparred publicly about same-sex marriage. It was “the kind of sparring only academics can have, where one academic writes a book in response to another's book”, says Scott.

Michael Warner argued that holding marriage as a goal for same-sex couples was insufficient for freedom, warning that it was mere assimilation to straight norms and would pacify LGBTI resistance. Andrew Sullivan argued conversely that marriage was not a neutering of the gay community's radical stance as anti-establishment, but that because being gay was normal, same-sex couples should be afforded the same rights to marry as anyone.

Scott's dissertation enters this debate from a post-apartheid South African perspective.

The debate between Sullivan and Warner is not sufficient for the South African context, Scott argues.

“What takes place in South Africa is more simultaneous adoption of what we would classify as straight marriage norms, but there's also a radicalisation of the couples through marriage. The radicalisation happens unintentionally but happens because the couples are pushing for marriage in an environment that does not believe they should marry.”

The making of a radical

Scott's mother couldn't write her matric exams in the 1980s because of the school boycotts. Forced to wait until 1993 to finish matric, his mother instilled a desire for learning in him.

Studying what it means to be an LGBTI couple in post-apartheid South Africa is “part of the democratic programme”, says Lwando Scott.

Studying what it means to be an LGBTI couple in post-apartheid South Africa is “part of the democratic programme”, says Lwando Scott.

His teachers wanted him to study commerce – “You will be rich,” they said – but, despite good grades in commercial subjects, he was drawn to social science as he worked towards getting to university. And when he got there, university was freedom.

“Freedom to think, freedom to speak, freedom to just be because the university environment allowed this or created space for it,” he says.

“Also, as a queer black kid growing up in the streets of Kwazakhele, Port Elizabeth, I found that social science gave me a better understanding of why my life was the way it was.

“It made me understand that apartheid was a social structure that inhibited the life chances of black people,” he says. “It made me understand that patriarchy was a social structure that oppressed women and men who did not fit the stereotypical male norm. Through social science I understood why my sexual identity was political. Or that I even had a sexual identity.”

Scott says that it was sociology that radicalised him.

“It was important for me to understand how these social structures operate if I was to have any chance of resisting them.”

“My politics will be intersectional or it will be bullshit”

To paraphrase the idea from feminist writer Flavia Dzodan, Scott insists that South African politics sorely needs to grapple with intersectionality.

“We can't only pick and choose the issues that we like and only use intersectionality for those moments,” he says.

We all have different identities and different ways of living and loving, Scott adds.

It's important to understand what that means on a national level, he says. The challenges faced by black LGBTI people, in different ways, need to be engaged with. This is why it is important to think about the consequences of things like same-sex marriage.

“Is marriage really for all LGBTI people, or just some? And if it is for all, why do certain people access it and others do not?”

He questions what we need to do to make sure that legislation like marriage is accessible to all South Africans, regardless of cultural and social barriers.

LGBTI issues are not the same everywhere, Scott says. The issues faced by poor and/or working class black LGBTI people are different from issues faced by middle-class white LGBTI people.

“So, depending whether you are the L or the G or the T in LGBTI, intersecting with your racial background, your economic background, and so forth, they bring up a unique life experience.”

“Of course, we don't want to be splitting hairs, but we need to be conscious of people's lived realities particularly because we have had such a horrible past of ignoring and actively suppressing people's lives.”

LGBTI in the postcolony

For Scott, the legacy of colonialism is inextricably linked to the lived realities for same-sex couples in South Africa.

“If one is doing research in South Africa, indeed Africa, we are confronted by the legacy of colonialism . . . The recent black hair politics in South African high schools is a case in point. We really need to engage with the history of colonialism and what it has done to us, and the remnants of it in our psyches.”

This is also important in the LGBTI community, he says.

“I think sometimes the LGBTI communities in South Africa, particularly white LGBTI people, often act like they are beyond colonialism and racism and misogyny,” Scott laments.

“Just because white LGBTI South Africans have experienced oppression for their sexuality, that does not absolve them from being part of the legacy of white racism in South Africa. And this means that within LGBTI spaces they need to be working at redressing the past, and be part of the conversation of what it means to be black and poor and LGBTI in South Africa . . . So, yes, colonialism and its impact are important to engage with in our context.”

For Scott, tackling colonialism is linked to “living the spirit of black consciousness”.

“This is what I am trying to achieve with queer consciousness – and, as you can see, it is a play on Biko's black consciousness,” he explains.

In the same way that black people have internalised “black inferiority” after centuries of colonialism, so do LGBTI people, and he argues that they need to rid themselves of the inferiority complex imposed by heterosexual society.

“If we are to truly experience the freedom we are always talking about, all this hard work needs to be done.”

Story Yusuf Omar. Photos Supplied.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.