Murder on the rise as South Africa fails to stem high crime rates

09 September 2016 | Story Anine Kriegler

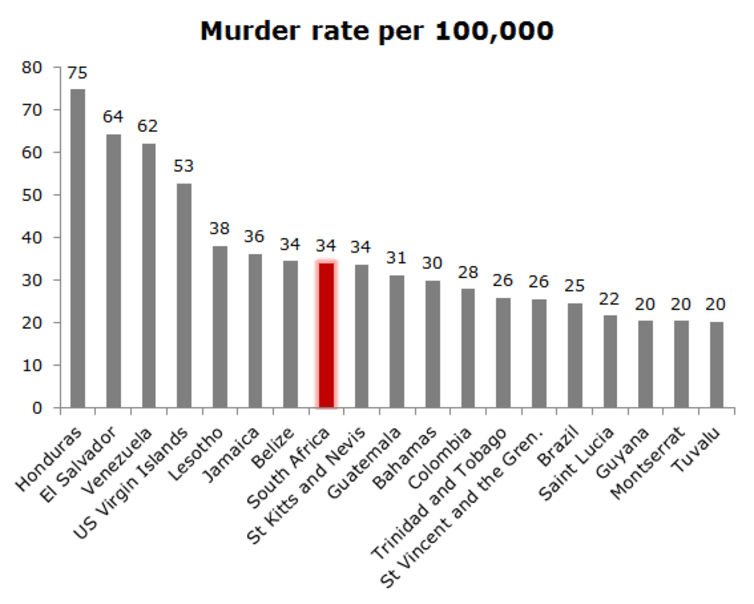

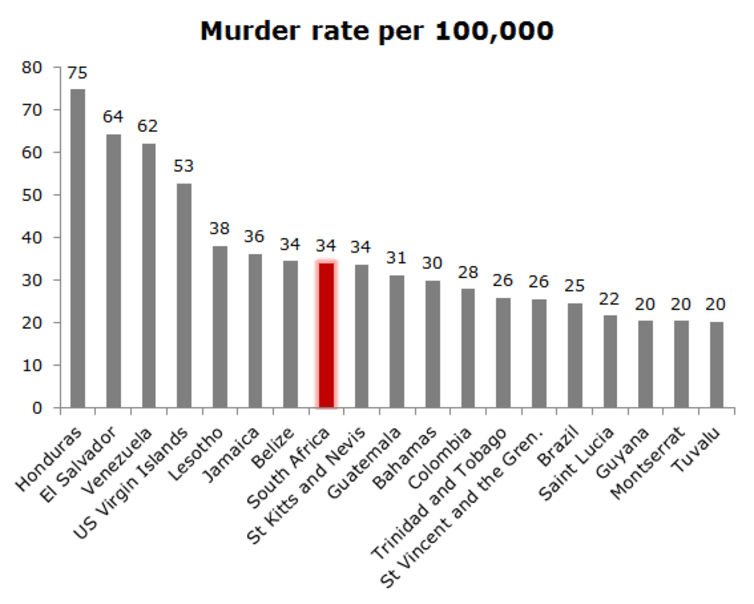

South Africa struggles with very high levels of crime and violence. Take the crime statistic on murder rates. The country ranks in the top 10 worst countries that report crime statistics according to the most recent data from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

Crime rate comparisons between countries are fraught with challenges and should be understood as broad indications rather than accurate quantitative relationships. Nevertheless, South Africa by any measure has a serious crime problem.

What insights can be gleaned from the latest annual crime statistics released by South Africa’s police?

To draw meaningful conclusions about longer term trends it is necessary to use rates per 100,000 people in the population. For the last few years South Africa’s police force has opted to publicise only the raw figures for the number of crimes recorded. This doesn’t account for population growth over time, or differences in population sizes between regions or towns.

The latest numbers had this to reveal about the five key crime types that are particularly worth watching.

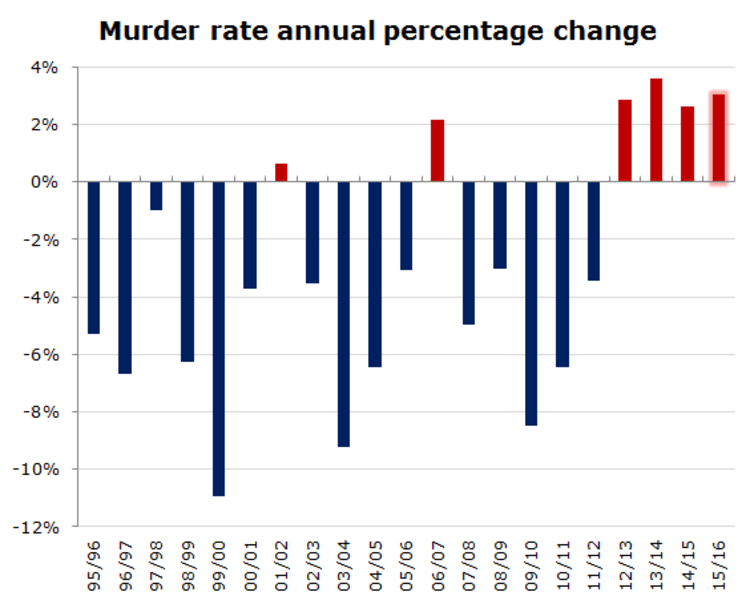

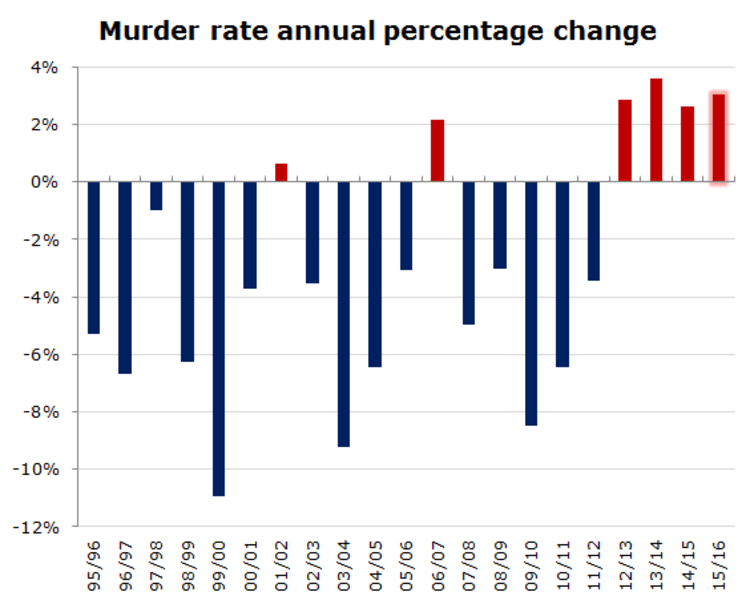

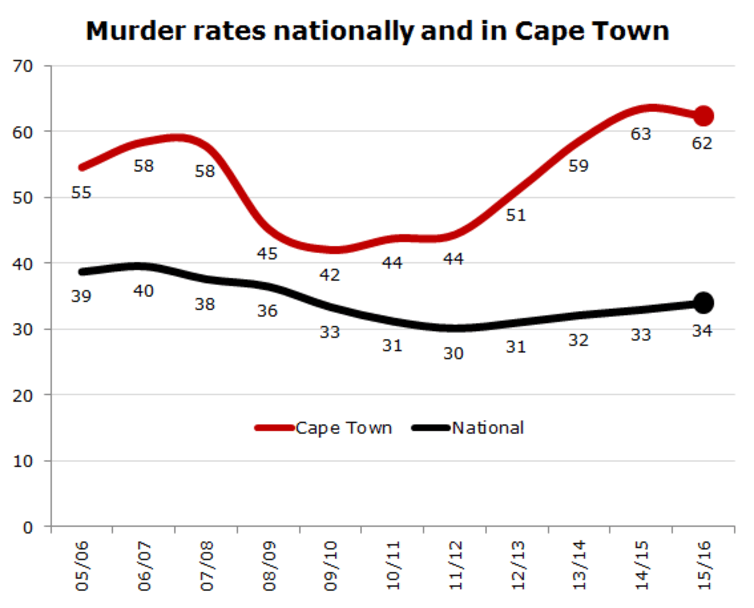

Murder rate: this has risen nationally for the fourth year in a row, from 33 per 100,000 in 2014/2015 to 34 per 100,000 last year.

More concerning than the overall high number of murders, which is by no means a new development, is the fact that its rate of increase has accelerated. Whereas the rise from 2013/2014 to 2014/2015 was by 2.6%, the rise from 2014/2015 to 2015/2016 was by 3.1%. This suggests that the recent increase in fatal violence is not slowing and that South Africa may be in for several more years of increase. The country urgently needs to work out why these increases are happening.

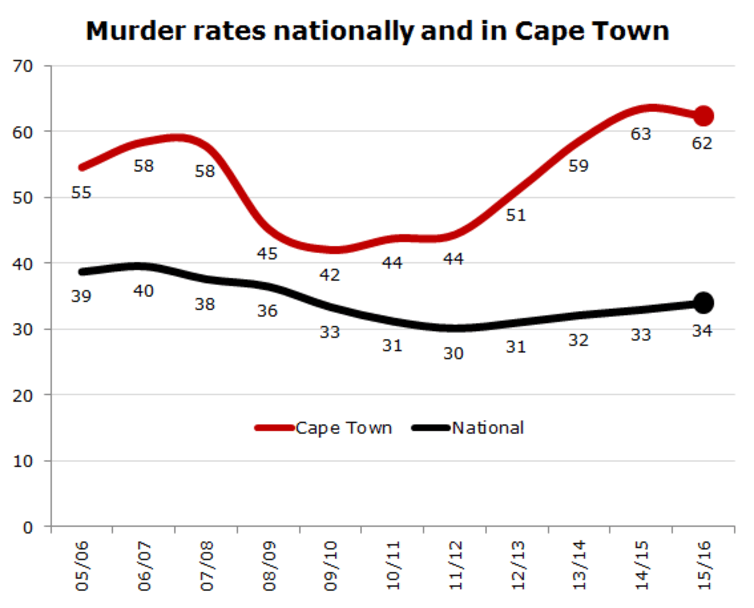

Murder rate in Cape Town: after five bad years, this may finally have turned the corner. Cape Town’s murder rate declined from 63 per 100,000 last year to 62 this year. This is a positive sign, but there is clearly a lot more work to be done. It is still at almost twice the national rate and among the highest in the world.

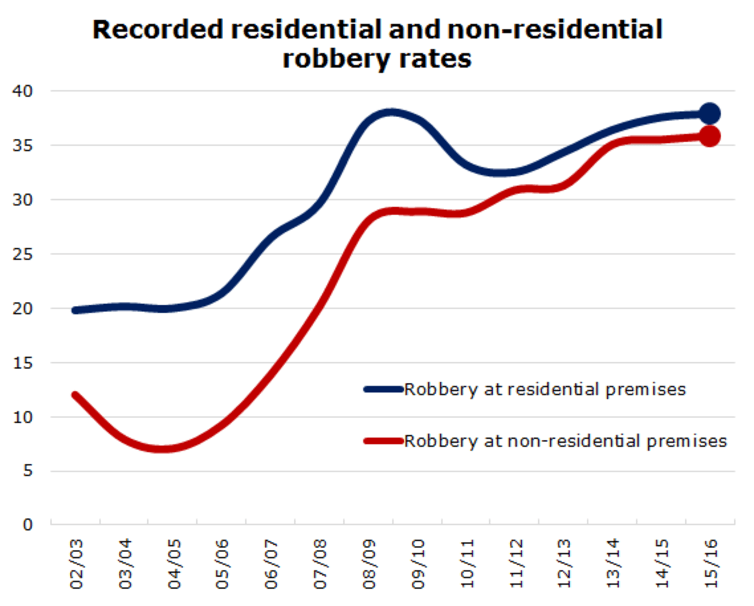

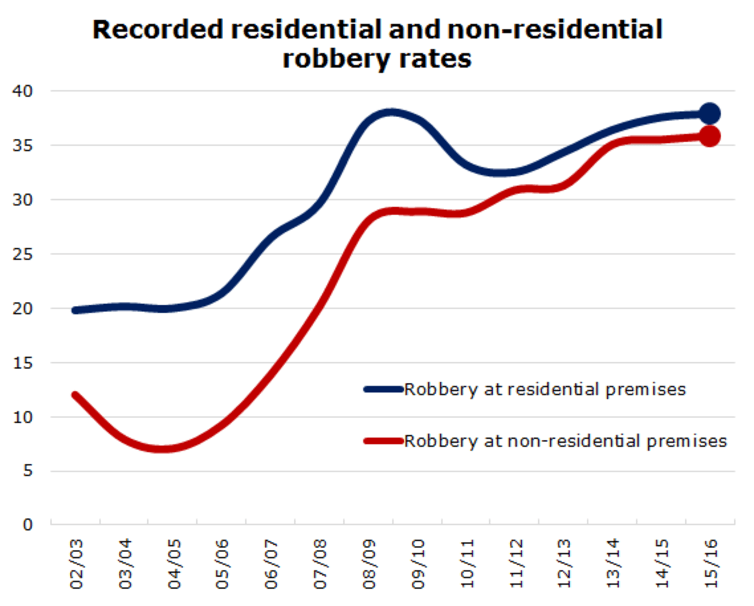

Aggravated robbery trends: The national rates of residential and non- residential robbery showed no decline although the rate at which they increased was smaller than it had been in years. Following the major increases between 2005/2006 and 2008/2009, it seems that relative stability in these crimes may have been reached. Turning them to a decline looks increasingly possible. The police should take heart.

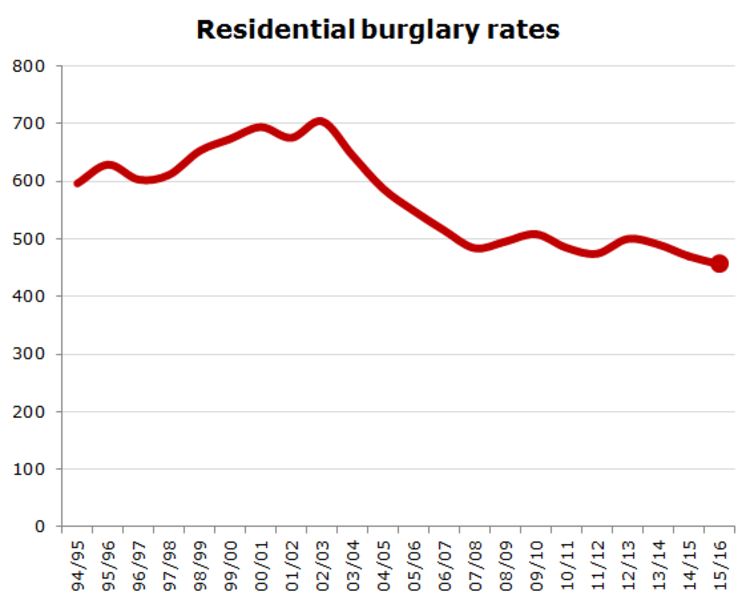

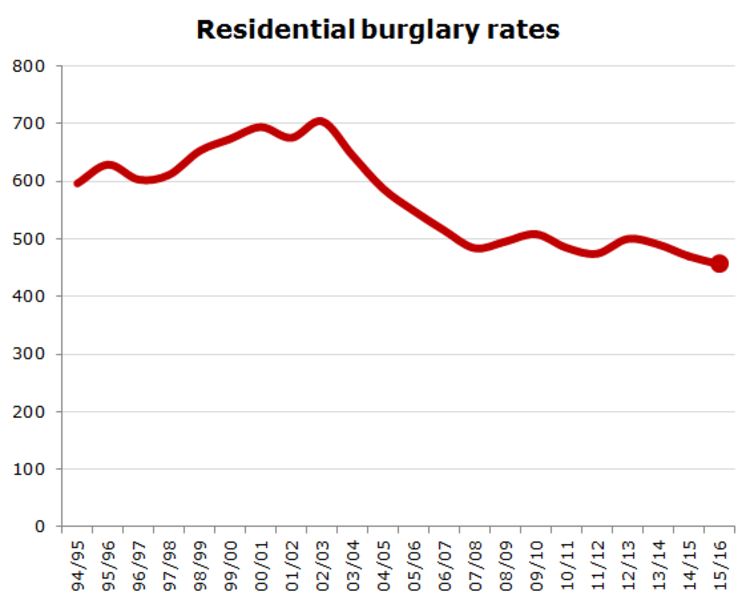

Burglary: Recorded rates of burglary have continued their long and fairly steady decline and are now about a third lower than they were 15 years ago. This should be a comfort given how much this crime contributes to public fear. It does, however, appear that people may have become less inclined to report this crime to the police. The upcoming Victims of Crime Survey should be watched closely to see if this trend continues and to what extent it may be contributing to recorded rates of decline.

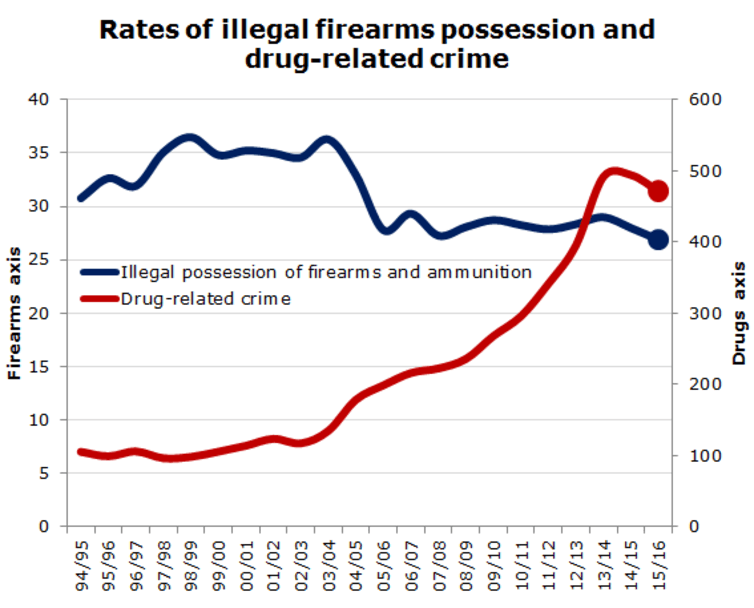

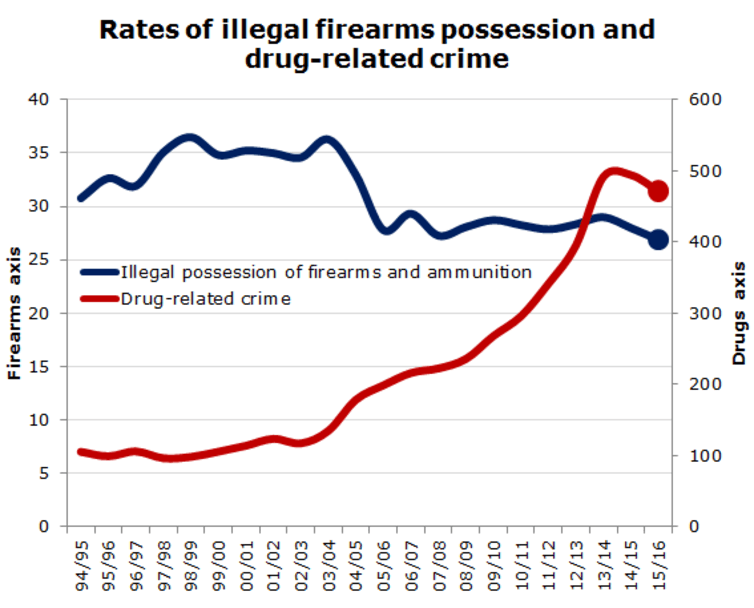

Drug-related crime and illegal possession of firearms: There has been a decrease in the recorded rates of drug-related crime for the first time in more than 20 years.

This could be the police’s new back to basics plan in action. Acting head of police Lieutenant General Khomotso Phahlane has championed a renewed focus on policing fundamentals and areas of under-performance. This may have resulted in resources being directed away from seeking out drug-related crimes.

Depending on where you stand on the issue of the desirability or effectiveness of drug prohibition, this may or may not seem like a good thing.

The rates of illegal firearm possession have also decreased slightly in the last year.

It is important to remember that national statistics say very little about how individuals experience crime. Each neighbourhood is different, which requires individuals to do a deep dive into the crimes reported at local police stations.

Anine Kriegler, Researcher and Doctoral Candidate in Criminology, University of Cape Town.

Crime rate comparisons between countries are fraught with challenges and should be understood as broad indications rather than accurate quantitative relationships. Nevertheless, South Africa by any measure has a serious crime problem.

What insights can be gleaned from the latest annual crime statistics released by South Africa’s police?

What the numbers say

To draw meaningful conclusions about longer term trends it is necessary to use rates per 100,000 people in the population. For the last few years South Africa’s police force has opted to publicise only the raw figures for the number of crimes recorded. This doesn’t account for population growth over time, or differences in population sizes between regions or towns.

The latest numbers had this to reveal about the five key crime types that are particularly worth watching.

Murder rate: this has risen nationally for the fourth year in a row, from 33 per 100,000 in 2014/2015 to 34 per 100,000 last year.

More concerning than the overall high number of murders, which is by no means a new development, is the fact that its rate of increase has accelerated. Whereas the rise from 2013/2014 to 2014/2015 was by 2.6%, the rise from 2014/2015 to 2015/2016 was by 3.1%. This suggests that the recent increase in fatal violence is not slowing and that South Africa may be in for several more years of increase. The country urgently needs to work out why these increases are happening.

Murder rate in Cape Town: after five bad years, this may finally have turned the corner. Cape Town’s murder rate declined from 63 per 100,000 last year to 62 this year. This is a positive sign, but there is clearly a lot more work to be done. It is still at almost twice the national rate and among the highest in the world.

Aggravated robbery trends: The national rates of residential and non- residential robbery showed no decline although the rate at which they increased was smaller than it had been in years. Following the major increases between 2005/2006 and 2008/2009, it seems that relative stability in these crimes may have been reached. Turning them to a decline looks increasingly possible. The police should take heart.

Burglary: Recorded rates of burglary have continued their long and fairly steady decline and are now about a third lower than they were 15 years ago. This should be a comfort given how much this crime contributes to public fear. It does, however, appear that people may have become less inclined to report this crime to the police. The upcoming Victims of Crime Survey should be watched closely to see if this trend continues and to what extent it may be contributing to recorded rates of decline.

Drug-related crime and illegal possession of firearms: There has been a decrease in the recorded rates of drug-related crime for the first time in more than 20 years.

This could be the police’s new back to basics plan in action. Acting head of police Lieutenant General Khomotso Phahlane has championed a renewed focus on policing fundamentals and areas of under-performance. This may have resulted in resources being directed away from seeking out drug-related crimes.

Depending on where you stand on the issue of the desirability or effectiveness of drug prohibition, this may or may not seem like a good thing.

The rates of illegal firearm possession have also decreased slightly in the last year.

It is important to remember that national statistics say very little about how individuals experience crime. Each neighbourhood is different, which requires individuals to do a deep dive into the crimes reported at local police stations.

Anine Kriegler, Researcher and Doctoral Candidate in Criminology, University of Cape Town.

This article first appeared in The Conversation, a collaboration between editors and academics to provide informed news analysis and commentary. Its content is free to read and republish under Creative Commons; media who would like to republish this article should do so directly from its appearance on The Conversation, using the button in the right-hand column of the webpage. UCT academics who would like to write for The Conversation should register with them; you are also welcome to find out more from carolyn.newton@uct.ac.za.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.