Unpaid women of Marikana prop up the mines

16 August 2016 | Story by Newsroom

When police were firing at mineworkers at Wonderkop in Marikana on 16 August 2012, UCT lecturer Asanda Benya was underground, working as a winch operator at a mine a few kilometres away.

Benya had been researching the experiences of women mineworkers in South Africa's platinum mines.

Her article, “The invisible hands: women in Marikana”, has been awarded the Ruth First Prize as the most outstanding article by an African author in the Review of African Political Economy for 2015.

After her first few visits and numerous conversations with women in the mining communities, Benya was struck by the role that they had played. And yet no one was talking about them and their contribution to the struggle for a living wage, Benya said in an interview with Humanities News.

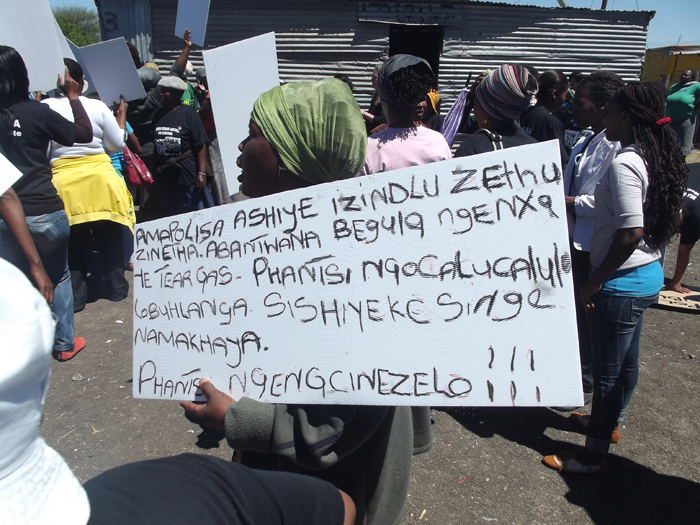

Women's unpaid toil is an essential but invisible component of the mining economy that simultaneously sustains and impoverishes them. Photo by Asanda Benya.

Women's unpaid toil is an essential but invisible component of the mining economy that simultaneously sustains and impoverishes them. Photo by Asanda Benya.

“With their permission, it seemed fitting to write their narrative, which was completely ignored at that time, and claim space for them, not as peripheral players, but as key actors who kept the Marikana spirit and flame burning when men were arrested, others injured and 34 killed.”

This research fills a gap that Benya identified – the role and place of women in mining communities and how they are affected by massacres like Marikana.

“To fully understand Marikana the event, one has to understand Marikana the location, and hence realities on the ground,” writes Benya.

Big Brother

Benya was struck by how the mines featured so prominently in the day-to-day lives of women who were not working for the mines – how the mine rhythms determined their getting up, their activities during the day and their going to bed at night. There was very little distinction between their personal lives and their lives as directed by the mines, she says.

“Their lives were largely ordered and organised by the mines in ways too intimate – it was shocking,” she added.

Many analyses of the Marikana massacre and its aftermath excluded the particular struggles that women in the area face, and the intimate ways that the mines dictate the pace of their daily activities. Photo by Asanda Benya

Many analyses of the Marikana massacre and its aftermath excluded the particular struggles that women in the area face, and the intimate ways that the mines dictate the pace of their daily activities. Photo by Asanda Benya

Conditions in the mining settlements were abysmal, writes Benya. There was little basic infrastructure.

“The lack of basic services, for migrants, symbolises lack of respect,” she argues. “Migrants feel left out and uncared for by the local government, by traditional authorities and by the mining corporations. None of these structures seem to care, support, safeguard or consider their needs or interests.

“Even in post-apartheid South Africa, migrants say they continue to be sacrificed for the benefit of capital and to the detriment of their livelihoods.

“At the root of the migrants' narrative are the multilayered ways the mines eat away their lives through what they describe as harsh, harmful and humiliating working and living conditions; the exclusions they face from traditional authorities because they originate from distant lands, and thus belong to different tribal or ethnic groups; and finally the ruling party, which has blurred and in some instances erased the line between government services and privileges for party members.

“Their stories capture the conditions under which labour power is reproduced and the nature of the post-apartheid order for many black mineworkers. Their chronicles of daily struggles for survival show how they navigate crises in the absence of services.”

The Marikana women's reliance on the mines for sustenance is a complex dance. Many women are regarded as 'out-of-towners' and are typically barred from finding work in the mines, so they rely on their husbands' or boyfriends' income. But the support they provide at home – emotional support, physical support (mining injuries are commonplace), cooking, cleaning, shopping, raising children – is seldom considered.

In a vicious cycle, the mining economy relies on a system of “cheap labour power, [which is] in turn reproduced by the invisible labour of countless women”, writes Benya.

Without them, the mines (and the cheap labour system) would not be able to exist.

Benya's full paper is available for free download from Taylor and Francis online until 30 June 2017.

Marikana remembered

Marikana commemorations at UCT included a screening of the documentary Miners Shot Down on 15 August 2016, the Left Students Forum hosted a worker speakout on Jameson plaza during lunchtime on 16 August and will host a discussion and slideshow about women in mining at 18:00 in the Centre for African Studies gallery, with Benya as the keynote speaker.

Story Yusuf Omar. Photos Michael Hammond / Asanda Benya.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.