The sex life of Earth's biggest bird

17 June 2016 | Story by Newsroom

A leading palaeobiologist at UCT helps unravel the biology of giant extinct birds five times the size of an ostrich but with the breeding behaviour of a goose.

They mated for life, the female reared the babies and shared parenting duties with the “big daddy” males, who also help protect their young.

This is how the mihirungs, of the family Dromornithidae, lived, according to UCT palaeobiologist Anusuya Chinsamy-Turan who was involved in an international study to unravel the biology of giant 8-million-year-old extinct birds more akin to a goose than an ostrich.

The birds were giant flightless birds unique to Australia.

They originated more than 25 million years ago and Genyornis, the last member of this group, went extinct in the late Pleistocene about 50 000 years ago. Their fossils are rare and fragmentary, so the biology of these birds is largely unknown.

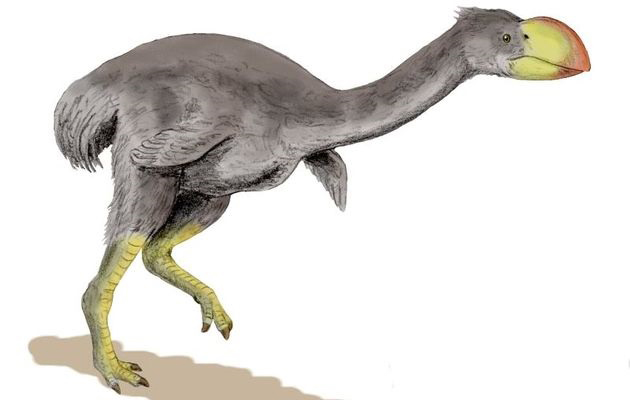

The largest of all mihirungs, known as Dromornis stirtoni, roamed Australia about eight million years ago.

They died in their dozens around a shrinking waterhole in the Northern Territory along with many marsupials, including sheep to cow-sized herbivores and their predators, distant relatives of the marsupial lion. Now, sleuthing by an international team led by Australian palaeontologists have revealed long hidden biology of Stirton's mihirung in a recently published article in the highly regarded Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

The Stirton's mihirung was “truly enormous”, the scientists said in a statement.

It stood two metres high at its back and with its neck and half metre long head could reach well over three metres.

“It was probably the largest bird ever to have lived. With an average weight of 480kg‚ it more than ten times the weight of an emu‚” said Warren Handley of Flinders University in Adelaide, South Australia.

“But it had a large size range‚ so the question arose‚ were there one or two species?” said Adam Yates‚ a co-author based at the Museum of Central Australia in Alice Springs‚ and the custodian of the main collection of these fossils. Detailed geometric morphometric analysis by Handley‚ as part of his honours research‚ showed that the fossils fell into two distinct size groups of similar-shaped birds.

Pencil drawing of Dromornis stirtoni, a flightless bird from the Late Miocene of Australia.

Pencil drawing of Dromornis stirtoni, a flightless bird from the Late Miocene of Australia.

To try and figure out which were males and which were females‚ the researchers decided to core the leg bones to look for medullary bone‚ a specialist type of tissue found only in the hollow bones of female birds before they lay eggs.

"When we drilled some of the bones‚ I was astounded to find that a few of them had medullary cavities filled with bone. What were the odds that this was medullary bone?" said Handley.

Samples of the bones were sent to Chinsamy-Turan, who is a specialist in bone histology at UCT's Department of Biological Sciences and prepared thin sections of the bone for microscopy.

She says‚ “It was quite a surprise to find that four of the birds in our sample had medullary bone. This finding was a real scoop since we now could say with certainty that these were ovulating female mihirungs.

"Our 'females' belonged to the group of smaller D. stirtoni individuals‚ with an averaged mass of 451kg (370–543kg)‚ suggesting that the species was clearly sexually dimorphic. The larger males had a mass averaging 528kg‚ with some reaching a massive 610kg in weight‚ much larger than elephant birds Aepyornis maximus of Madagascar‚ or the giant moa Dinornis robustus of New Zealand."

The large terrestrial birds that survive today are all ratites - the largest of which are the ostriches that weigh in at about 145 kg‚ and the smaller 40 kg cassowary and emu. Among ostriches‚ the males are larger than the females‚ while in most other ratites‚ the females are the larger sex.

Scientists involved in the study: Trevor Worthy and Warren Handley from Flinders University in Adelaide and Anusuya Chinsamy-Turan in the middle.

Scientists involved in the study: Trevor Worthy and Warren Handley from Flinders University in Adelaide and Anusuya Chinsamy-Turan in the middle.

UCT's results for the Stirton's mihirungs show that the males were larger and equally abundant as females‚ and so a breeding behaviour more like geese can be inferred.

"Most likely‚ they mated for life‚ the females brooded the eggs‚ and both sexes aggressively defended nests and shared parental care. With their huge size‚ they were capable of protecting the growing chicks from predators‚ such as the dog-sized ancestral thylacines and marsupial lions that were around at the time," says Chinsamy-Turan.

“This study provides a spectacular example of how the integration of multidisciplinary techniques and collaboration can reveal details of the biology of long extinct animals from their fragmented osseous remains,” says Flinders University's Trevor Worthy.

Story by Times Live. Republished with kind permission. Images supplied by researchers. Pencil drawing of Dromornis stirtoni by Nobu Tamura, CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.