Renegade Reels is a rebel in its own right

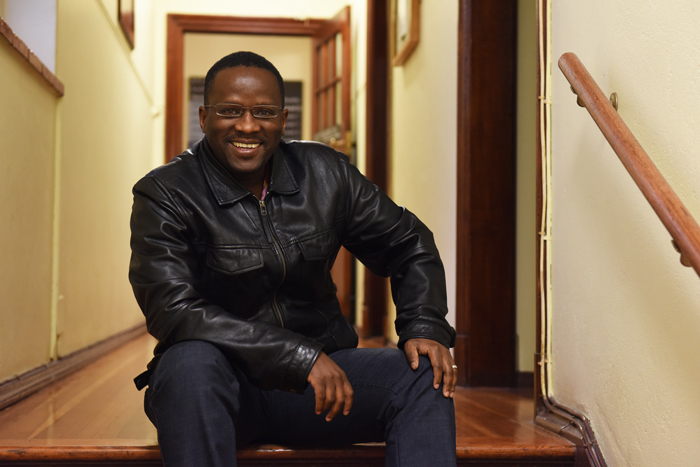

13 June 2016 | Story Yusuf Omar. Photo Michael Hammond.

Dr Litheko Modisane is 2016's winner of the UCT Book Award. The senior lecturer at the Centre for Film and Media Studies won the award for his inspection of the circulation and reception of anti-apartheid cinema, titled South Africa's Renegade Reels: The Making and Public Lives of Black-Centred Films. Yusuf Omar spoke to Modisane about his winning work, which breaks new ground for traditional ways of analysing films.

YO: Congratulations on winning the UCT Book Award.

LM: I couldn't believe it. I wasn't expecting that. It was a really big shock. Even now, I'm still dealing with the enormity of the award, with the reality of having won it. As time goes on, the shock is getting bigger, because it's sinking in.

YO: South Africa's Renegade Reels … Let's talk about the book.

LM: The book is really about the making and the publicness of the films I speak to: Mapantsula (1988), Come Back, Africa (1959), uDeliwe (1975), Fools (1998) and television series Yizo Yizo (1999, 2001). I look at films from the late 1950s through to the late 1980s and others that were made in the post-apartheid era.

I'm trying to understand that. The methodology that has been mostly used by film scholars is to read exegetically, that is, to go into the films and try to understand what they are saying, read between the lines, read against the grain. That's important. That is still significant. But there was something else that wasn't happening.

One could expand this methodology and understand that these films are not just texts that are there to be read, but are material objects that circulate and are watched by viewers around the world. As they circulate, they are doing something else, outside of what a scholar sitting in a university might be thinking.

They are also affecting the way people see things wherever they are watched. They are calling people into this kind of discursive bubble called a 'public' – by public, I mean this abstraction that comes into being in relation to these films as they circulate and are engaged with.

So a film like Mapantsula or Come Back, Africa is affecting, mobilising certain social and political entities, and thoughts and reflections against apartheid, but also giving birth to ideas that might not have been foreseen by the filmmakers. They give birth to a space of reflection – a public sphere, if you like – about issues that the film raises, and perhaps even issues that are broader than the filmmakers anticipated.

YO: What are some of the issues that audiences watching these films might have engaged with?

LM: Mapantsula, for instance, deals with what happens when you have people who are not 'comrades' actually being the focus of the film. You've got a central character that's a tsotsi and not a comrade. This is at a time when the liberation movements, particularly the ANC, thought it important to have comrades, people who are politically conscientised, as subjects of these films. So what happens then?

Basically, the filmmaker challenges the liberation movement's assumptions about how to address issues such as discipline of combatants or comrades on the street level; how to deal with people's conscientisation politically, or the lack thereof. And there are issues of gender – the participation of women in the struggle. Are they central, or are they just adjuncts to the mobilised male bodies in the political field?

So Panic, the central character in Mapantsula, becomes important because he serves as this device of ambiguity. How do you deal with a tsotsi when you are a comrade? You don't want to deal with that kind of person. But the reality is that there are tsotsis even among comrades! So you have to address that.

The publics that are forming around Mapantsula therefore pick up this character and try to dissect its importance, or lack thereof. At the end of the day, people understand that you need something like this in order to make people think and reflect on certain questions.

Other films, like Come Back, Africa, were banned in South Africa and circulate mainly in the USA. Does this mean it has no public in South Africa? That is the question that prompts me to focus on this film as it goes to countries like the USA, Canada and Italy.

What it does when it circulates is to raise issues faced by, say, African Americans, who might start to see a resonance between the issues they face and the challenges black South Africans faced under apartheid. So what does the African American community do with this film?

You've got people who are already invested in using film as a springboard for political mobilisation, and they take up the film. It's not a given that people will then be excited by issues, such as finding out what apartheid is all about. But you find these kinds of discussions taking place.

The film prompts certain perspectives on apartheid that mobilises certain communities to see apartheid not for how it is represented by the US government's propaganda machines, but by an independent filmmaker who decided to show the audiences something they weren't being shown in mainstream media.

YO: With this approach in mind, how do your students respond to your teaching?

LM: It's varied. The way I approach film, as you can see with this book, is quite different to how they've been taught about film. There's resistance, but there's also excitement in class. A student made a confession to me: he actually enjoyed this angle because he never realised that this kind of connection could be made. But he mentioned one person who couldn't see these connections, or even the usefulness of making such connections.

As you would know, most of our students are predisposed to enjoy and engage Western and particularly American texts, rather than local or African texts. It's a struggle to find that balance. You don't want to alienate students. At the same time, you want to make them aware of, and teach them things that apply at a local level.

They are living at a time when exposure to cultural artefacts is so intense; it kind of defies the logic of national boundaries. They are a very international bunch, culturally speaking. They cross cultural borders. One must always engage this crossing.

YO: That's a tricky balance.

LM: It's a tricky balance. Their idea of Africa has to be constantly challenged. It's an idea of Africa that's constantly trapped within certain logics of binaries, certain logics of difference.

One always has to say that this is a different time, actually. You need to understand that the 'time' of Africa and the 'time' of the entire world, including the West, are not necessarily dissimilar. That denial of coevalness, as Johannes Fabian has argued in his brilliant book, is actually a thing of the past.

We need to think beyond that anthropological gaze that puts Africa at the infancy of the world, at the infancy of history.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.