Scholar's search uncovers UCT's first black medical doctor

12 April 2016 | Story Chido Mbambe. Photo Michael Hammond.

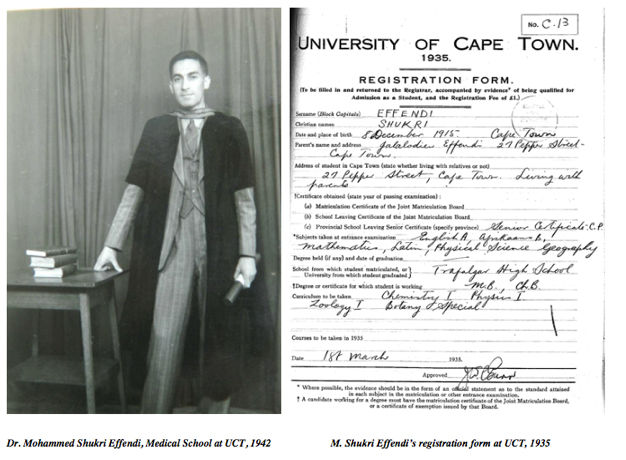

Halim Gencoĝlu, a UCT doctoral student from Turkey, has discovered that Dr Muhammed Shukri Effendi was the first black medical student to graduate from UCT. Effendi, who studied at Trafalgar High School, went on to pursue his studies at UCT medical school and graduated as a medical doctor in 1942. Previously, it was thought that Maramoothoo Samy-Padiachy, Cassim Saib and Ralph Lawrence were the first black medical doctors to graduate from UCT – in 1945.

With a keen interest in colonial history, Gencoĝlu studied honours in the History Department in 2011.

“While doing my honours with Professor Worden, he suggested that I write something using Turkish sources. The late Professor Shell inspired me to research Ottoman presence in South Africa using Ottoman/Turkish archival materials. I thought that these sources could perhaps offer us new insights into historical events in South Africa and the continent,” explains Gencoĝlu.

Using South African and Turkish archival sources, Gencoĝlu uncovered evidence to suggest that Dr Muhammed Shukri Effendi was actually the first black doctor to graduate from UCT. These sources include UCT registration papers and documents from the Effendi family.

“A South African medical journal published on 27 July 1946 shows that Effendi was a qualified doctor already and moved his practice to a stone house in Mountain Road in Woodstock. The building was called 'Erzeroum', named after his grandfather's birthplace,” says Gencoĝlu. This was after having worked briefly at Groote Schuur Hospital and in his own surgical clinic in the Bo-Kaap.

Left: Effendi qualified as a medical doctor in 1941 and graduated in February 1942. Right: Effendi's registration papers at the UCT medical school. Read "A rare case of restorative justice" on the Faculty of Health Sciences website.

Left: Effendi qualified as a medical doctor in 1941 and graduated in February 1942. Right: Effendi's registration papers at the UCT medical school. Read "A rare case of restorative justice" on the Faculty of Health Sciences website.

His research also shows that the first black female doctor in South Africa was Dr Effendi's cousin, Dr Havva Khayrunnisa, who graduated in London in 1920. She moved to Istanbul where she worked as a gynaecologist to fulfil the conditions of the bursary awarded by the Ottoman government. She eventually practised in Cape Town after the death of her husband in Holland in 1929.

Gencoĝlu's article, “Forgotten Medical Doctors, Dr Muhammed Shukri Effendi and Dr Havva Khayrunnisa”, was published in the Bulletin of the National Library of South Africa in June 2015. In the article he argues that although the fair-skinned doctors Effendi and Khayrunnisa were of Turkish descent, at that time in South African history they would have been classified as non-white due to their religious identity as Muslims.

“It is an interesting fact that Dr Shukri Effendi was admitted merely on the grounds of his physical appearance, rather than his non-white identity,” says Gencoĝlu.

Furthermore, Gencoĝlu explains that earlier researchers may have overlooked Dr Effendi because they were confused by his ethnic and national identity. Dr Effendi's fair skin and his well-known Turkish family background (as the grandson of Professor Abu Bakr Effendi and nephew of Dr Abdullah Abdurahman) might have contributed to his acceptance at UCT at the time.

“This is relevant in the context of apartheid in South Africa when, prior to 1943, universities were subject to strict laws of racial segregation and did not allow non-whites to study at UCT,” observes Gencoĝlu.

The classification of the present generation of the Effendi family puts the historical matter into context. A copy of the ID of a living member of the Effendi family, Hesham Nimetullah Effendi, clearly shows he is regarded as a Cape Coloured despite his fair skin colour.

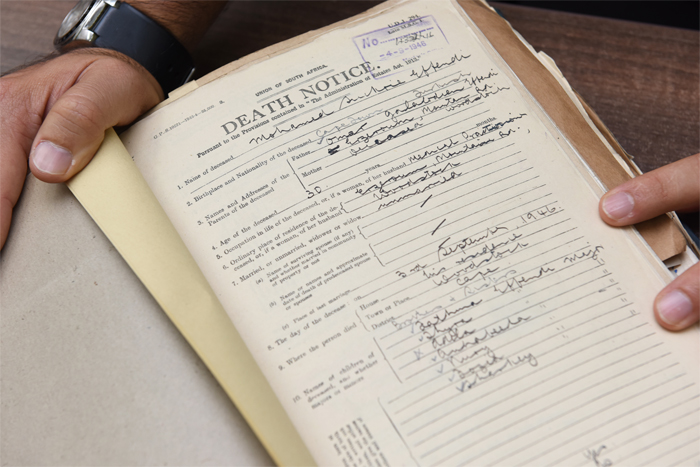

“Even when I looked at the death records, the Effendi's were referred to as Asiatic or Malay; that's what made them non-white,” notes Gencoĝlu.

The death record of Dr Muhammed Shukri Effendi, clearly showing his occupation as a medical doctor.

The death record of Dr Muhammed Shukri Effendi, clearly showing his occupation as a medical doctor.

On the other hand, Effendi had a Turkish classmate, Dr Reginald Remzi Bey, who was the son of Mehmet Remzi Bey, the first Turkish ambassador in South Africa. He was classified as white because he was raised as a Christian and studied at SACS. He graduated in 1938, four years before Dr Effendi, who graduated in 1942.

Dr Effendi passed away at the age of 30 after contracting tuberculosis, which Gencoĝlu believes may have contributed to his obscurity in history.

Gencoĝlu is currently completing his PhD in Hebrew Studies at UCT and hopes that scholars will study further on the topic, as his research is only the tip of the iceberg.

“There is an old Turkish saying by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk which says, 'Writing history is as important as making history. If the writer has no allegiance to the makers of history, the irrefutable facts become incomprehensible to human beings,' ” explains Gencoĝlu. “So I think history should be a compulsory subject in schools as the youth need to read history in order to see the future. They need to access different sources, which are not influenced by politics, in order to expand their historical knowledge and critical thought.”

He plans to continue with his post-doctoral studies as he feels he can provide rare knowledge to UCT because of his diverse educational background.

“As you can see, history is like a puzzle for me. I find bits of information and piece them together to get the whole picture.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.