The Bremner chapters

29 January 2016 | Story by Newsroom

Registrar Emeritus Hugh Amoore served a marathon 42 years at UCT, amassing a wealth of institutional knowledge and many admirers of his no-nonsense style, not without its idiosyncrasies. He spoke with Helen Swingler on the eve of his retirement in December 2015.

Asked how many committee meetings he'd attended in 42 years at UCT, including 29 years as Registrar, Hugh Amoore's answer is characteristically to the point.

“They are not innumerable. But they are significant in number. I don't know.”

It's not often UCT's most senior administrative officer will end a sentence with a hanger. Having served five of UCT's nine vice-chancellors, Amoore is recognised as an institutional sage: a vault of institutional and general knowledge, amassed in the formal and informal workings of the university; logged in minutes, briefs, reports, meetings and notes – and often in the hallmark calligraphic writing he learnt as a schoolboy in Pretoria.

He'd arrived in that city as a three-month-old with his parents. After high school in Grahamstown he completed national service, came to UCT as a BA student (English Literature and Applied Mathematics) in 1970 − and never left.

Back then

In 1970 there were 7 000 students on campus (there are 27 000 now) and 800 places in residence (now there are 6 600). From the start, Amoore busied himself in a raft of activities, from sport to debating. He captained the cross-country and athletics club and, as a member of the SRC in 1972/73, was involved in the Sports Union and Sports Council. He was also a sub-warden at Kopano (then Driekoppen) residence.

With no idea what to do after graduating he took the post offered him in Student Affairs; an opportunity to work while figuring out his future.

By the end of 1975 Amoore had moved to the Registrar's Office where he was the handlanger for the then registrar Pat McDonald. Three more appointments followed: Academic Planning Officer in 1978, Academic Secretary in 1984 and Registrar in 1987.

“I got enmeshed in the university business as a student and never got 'unenmeshed'. It interests me.”

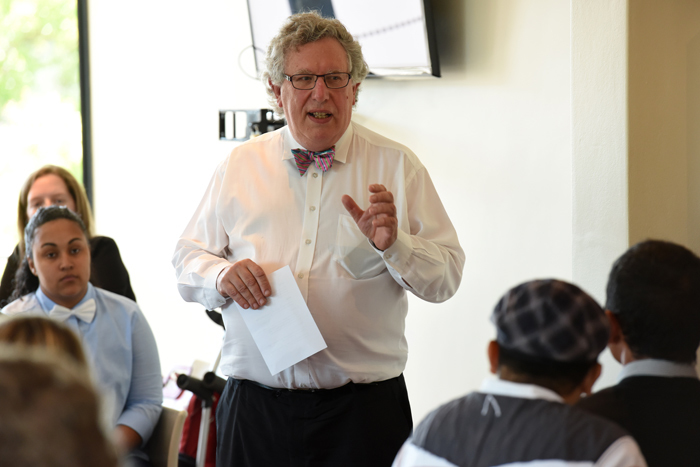

Amoore became a familiar figure over the years: a clutch of files buried under one arm, noted for his self-tied bowties (many the handwork of his daughter Ruth), and Lamy fountain pens that live in an oxblood leather pouch.

Maelstrom year

He probably never imagined the tumult of 2015 as a coda for his long career.

But he's unfazed, even by the brusque treatment from protesting students who scrawled derogatory graffiti outside his office after occupying the Bremner Building, and even when he was harassed, spat at, insulted (like many others) and labeled “that apartheid registrar”.

There is a small irony in the label, which he doesn't mention but which emerges strongly among the anecdotes of colleagues.

At the height of apartheid in the 1980s, Amoore manipulated the system, bookended by apartheid laws, to allow black students to get Ministerial permits (the device was to include a “permit subject” in one's intended curriculum) and to create closed corporations (CCs) to allow black staff to purchase housing near to the campus when the Group Areas Act was still in force.

But he shoos this aside. The comments are born of ignorance and provocation and a rhetoric that dismisses the past. The context is important.

At one of the many farewell functions in his last weeks at UCT, Ingrid Fiske, aka poet Ingrid de Kok, spoke of his humanity − and his long-term view.

“Even in the recent turmoil, after a hostile, physical confrontation with an angry group of students, he took the historical perspective. He spoke movingly of the need to keep the university a sanctuary for student protest … To maintain the long, depersonalised view even in times of stress seems to be quite remarkable.”

For Amoore it's now about harnessing change.

Sea changes

“UCT has experienced many sea changes and there have been periods in its history when that change happened gradually or cataclysmically – and it had been happening cataclysmically in 2015.”

“One has to look at 2015 on a much longer timescale and only then can you say what effect it had on the university. It's a year that had difficulties, but we achieved quite a lot of things. We've got to get through this.”

One of those achievements was an end to outsourcing.

“We've been wrestling with outsourcing for the past 20 years and prior to that we wrestled with the issue of internal wage disparity. The great strike of 1991 was about that. In the 80s and 90s there were significant moments that brought about a better social order within the university community. And insourcing in 2016 is going to be another step in that process of moving towards a more just social order.

“It's another step in a continuum that's been with us for 30 years.”

It's taken a coming of age, nearly 21 years after the hiatus of 1994, for student protest to re-emerge to tackle important issues: access and equity and the cultural baggage of colonialism remnant in universities, and externally, high fees and shrinking resources for higher education: the outfall of a regime grown neglectful and complacent.

Handbook for registrars

As registrar, Amoore was immersed in the day-to-day running of a large and highly complex institution. He was secretary to the Council, Senate and Convocation, and responsible for academic administration and legal issues across the university. He chaired the Board of Trustees of the UCT Retirement Fund and for many years the Works of Art Committee, was the Vice-Chancellor's nominee on the Baxter Board and its EXCO, and was a UCT-nominated director of the UCT Private Academic Hospital. His day-to-day responsibilities included the internal audit function. Externally, he chaired the Matriculation Board and was a member of the Admissions Committee of Higher Education South Africa (now Universities SA).

Handbook for registrars

What tips would he put in a handbook for registrars?

“First, you've got to be a competent administrator and a competent manager of people. The first is important.

“Second, you have to be alive to the political issues, externally and internally in the university.

“Third, you must have a well-developed sense of process. And then, finally, you have to be on top of the tools of the trade, and some of those are linked to my first point.

The key tool of the trade is committee work. Another is the technical knowledge of university legislation and policy, the HEMIS reporting system and how HEMIS relates to state funding.

“And you have to establish a network with your peer registrars around the country and working relationships with the officials in the Department of Higher Education.

But you must know the university, Amoore adds.

“Even if you have all the rest, you must understand how it's put together and how the different sectors relate because, inevitably, people will knock on the registrar's door for answers.”

Five sea changes

Sifting through 42 years, Amoore selects five sea changes.

“In the late 1970s for the first time we had to regulate admissions and growth and so we set limits for enrolment and selection processes that would yield the class sizes that we wanted.

“That was radical for South African universities because prior to that you took everyone who was qualified (not in medicine though). But in 1977/78 we had a surge in applications for the BCom degree such that it just overwhelmed all the departments involved, from mathematics to economics to accounting and law. We also realised we had to regulate admissions in the context of developing equity and transformation and we've continued to do so with increasing levels of sophistication.

“The second sea change happened in 1980/81 and it's best to understand that in the context of the increasing realisation, post-1976, that so-called open universities had to start changing gear. So 1980/81 saw the beginnings of what is now the academic development programme (at the time the academic support programme), which was radical, and the recognition that the ASP/ADP programmes would not succeed without concentrated efforts to find bursary support and to provide housing for black students. The planning started in 1980 and got off the ground in 1981/82.

The next sea change, which helped accelerate the second, was that the government began to get “uncomfortable” with the permit system where a student of colour had to get a permit from the minister of state to register at UCT, a university designated by the government as a university for whites.

“Later, government asked if we'd accept the abolition of the permit system for a system of quotas. [Minister Piet] Koornhof didn't articulate a quota system. He said he would want a guarantee from universities that they would preserve their culture. I remember [Vice-Chancellor Sir Richard] Luyt saying that he'd told Koornhof, 'Well, what is the culture that you want me to preserve?'.”

That then became Minister Gerrit Viljoen's race quota proposal and UCT lead opposition to the quota bill, enacted by Parliament but never implemented, one of several interesting pieces of legislation that were put on the statute in the 1980s but never brought to implementation, says Amoore.

“But it was part of this awkward recognition by government that what they were trying to do was not working. At the same time, having sounded out the minister, we simply opened residences, technically still in contravention of the Group Areas Act.”

Then came the next round of staff and student bannings in the 1980s under the Terrorism and Suppression of Communism Acts. By the late 80s UCT frequently saw police and teargas on campus.

In 1987 the Minister of National Education published regulations that imposed conditions on the receipt of state subsidies, which would have allowed the state to reduce UCT's subsidies “if we were not behaving”.

“We made an application to the court to have those regulations declared ultra vires, which we won. It all signalled the crumbling of separate development, and all that implied for UCT.”

Change for survival

The next major change came in the wake of Dr Mamphela Ramphele's 1996 appointment as vice-chancellor, ushering in a period of intense reforms, not all successful and not universally popular, but which Amoore says were vital for UCT's continued existence in the 21st century.

“Mamphela reorganised the way the administration was structured and she initiated the reorganisation of faculties and changed the basis for budgeting.

“The faculties became budget units. There was devolution of financial authority to the deans and UCT moved from having “part-timers, collegially elected, collegially operating to executives”.

She also had a profound effect on black students and staff at UCT.

“And we're seeing a new manifestation of that in 2015 with #RMF and the movements to “decolonise UCT”. Prior to Dr Ramphele's influence there was some ambivalence: if you were a black student at UCT and doing well academically at UCT it was thought that you weren't doing your bit for the struggle. Mamphela changed that. You could see the black consciousness philosophy coming through.”

The year 2015 has also seen a sea change.

“And there will be no going back on how we transform to a more inclusive symbolism,” Amoore adds. “It's got to be done but it's not going to be easy.”

Next chapter

Opening a new chapter hasn't been easy either. Amoore's new title, Registrar Emeritus, has brought home the sea change in his own life as he hands the baton to long-term colleague, Royston Pillay.

“I think about a month ago I was in denial about actually retiring. It was a sense of simply being incapable of letting go. But I recognised that I had to do it.”

Will he stay in touch with UCT?

“From a distance, and only when needed. It's very important not to interfere once you leave.

“There's a lot that I would like to have done and wrapped up and sorted [at UCT] before the year-end that simply wasn't possible because the year was such an eventful one,” said Amoore.

“But I suspect I will look back and say I was glad I was there in 2015.”

He's going to do “a small thing for Summer School” when he'll be in conversation with Lizette Rabe who's written a history of Die Burger, to celebrate its centenary, and important milestone in South African media history.

Amoore will ease back into home life, shared with the three special women: wife Kate, daughter Ruth a UCT BSc student who hopes to major in genetics and chemistry, and Mary, his mother, who will be 103 in January.

He'll also devote more time to philately, “an all-encompassing but not all-consuming hobby”.

Amoore plans to take an exhibit, a study of the postal history of the official mail of the Cape of Good Hope, 1806 to 1910, to the 4th World Stamp Exhibition 2016 in New York in May.

Will he write a memoir?

His expression is inscrutable.

“Perhaps.”

Photo by Michael Hammond

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.