How well can you remember a nose? The problem with identikits

20 May 2015 | Story by Newsroom

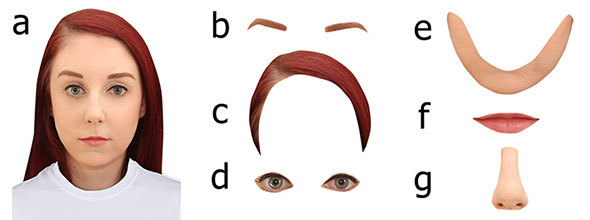

A study has found that we recall faces better when we think of them in their entirety, rather than feature by feature. This could have significance in the world of crime-solving, where 'featural' identikits are still used.

Close your eyes for a minute. Try and imagine a facial feature, of a person you see pretty regularly; his or her nose, for instance. Think of its every ridge and groove, the shape and size.

Now imagine you only have a few seconds to glance at an assailant, a stranger; and then you're called in much later to construct an identikit, feature by feature. Not that easy, right?

If you answered yes to that, you're not alone. The accuracy of identity parades and police identikits has been getting some airtime in recent years, particularly after a landmark US study that found incorrect identification by eyewitnesses was a factor in over 70% of wrongful convictions. The study culminated in the US Innocence Project, which led to the freeing of 329 wrongfully convicted people, including 18 who'd spent time on death row.

Spurred on by the US study, psychology postdoctoral student Kate Kempen set about finding out if people could identify individual features from line-ups. What she found was that identifying features in isolation is near impossible.

Kempen is excited about the project – firstly, because it exposes some faults in the international police system of drawing up identikits; and secondly, because it could form part of more extensive research that may ensure that fewer innocent people are locked up for crimes they did not commit. Or at least ensure more accurate line-ups in identity parades.

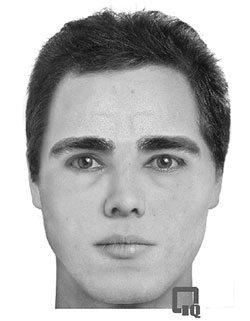

Many people have been wrongly convicted on the basis of identikits like this one.

Many people have been wrongly convicted on the basis of identikits like this one.

"In the Innocence Project, where people were freed after being wrongfully convicted, it was found that in many of these instances the person had seen the criminal; and in many cases, had been required to construct a composite, to aid in the apprehension of a suspect. And in many of the instances, no DNA evidence was available," said Kempen.

"The statistics are very chilling, especially since 18 of these people were on death row – and fortunately, were exonerated. It's horrifying to think how many people must have passed before ..."

Throughout her honours and master's years, Kempen conducted multiple studies: to tease apart the various aspects of face processing and recognition, and to investigate whether composite (feature by feature) construction impacts negatively on memory, and why that happens.

This latest study shows that – in terms of constructing composites – it's not easy to identify individual features from photos. She found an incongruence in the memory's processing and recognition of faces, and how we construct them. "Indeed, even constructing the face of someone you see daily, feature by feature, would be difficult."

Kempen is a woman passionate about crime – "not doing it, but solving it", she laughs. She says her study had importance more specifically because the process of the construction of these composite faces (for identikits) relies on taking a fully-formed 'whole' and 'holistic' memory in your head, and attempting to break it apart into individual face parts.

"During composite construction, victims and eyewitnesses are typically required to search through libraries of hundreds of features in order to find an appropriate-looking feature that best matches that of their memory.

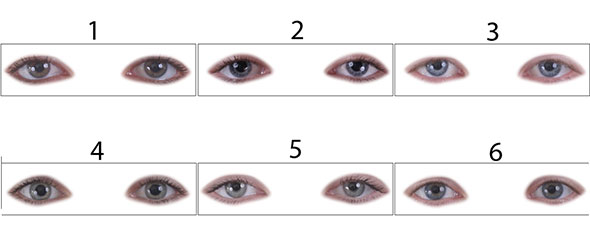

"So for a recent poster presentation, I had participants study a target face, then attempt to identify, say, the nose belonging to that target from a line-up of six noses (one target nose, five 'distractor' noses). I did this for various facial features. And participants found it to be an impossible task.

Would you be able to remember and differentiate easily between isolated eyes like these? Most of Kempen's participants were not able to do so.

Would you be able to remember and differentiate easily between isolated eyes like these? Most of Kempen's participants were not able to do so.

"So it got me thinking: if people can't even identify the correct feature from a six-option multiple-choice line-up, when it comes to looking through hundreds of features in a composite construction book ... they stand no chance.

"This, ultimately, would be the overall 'quality' or 'resemblance' of the composite to the perpetrator. And there have been many cases where people have been apprehended based on resemblance to a composite. There is also lots of research suggesting that when you create a 'poor-quality' composite that doesn't represent the intended person, this leads to a decrease in accurate line-up identifications.

"So our job is to try to make the best face possible, seeing as a) innocent people may mistakenly resemble a composite, and b) the production of poor-quality composites affects the decisions we make when faced with a line-up.

"The methods used to construct faces in the South African Police Service (SAPS) currently are these feature-based programs – in which you have to look through many facial features on their own. There are more 'holistic' methods of face construction that are in use, particularly in the UK.

"My supervisor, Professor Colin Tredoux, has also developed a program with an interdisciplinary team of collaborators at UCT (in engineering, mathematics, and computer science) which attempts to move away from the 'featural' aspect of construction, and instead 'breeds' together faces that you may think match your memory of the perpetrator. Thus, by choosing lots of different faces with different elements and 'breeding' them together in this computer program, we may arrive at a closer, more realistic representation of a criminal.

"We have been in talks with the Facial Identification Unit of the SAPS in the hope of introducing these newer methods into law enforcement – to see if there is an improvement in composite quality, and an increase in accurate composite-to-face matches, and ultimately a decrease in incorrect identifications."

Kempen, 27, with her fire-red hair and bright red lips, jokingly says she makes sure she highlights her distinctive features "just so that I can never get confused [for someone else] in a line-up".

"Throughout my life I've always had a passion for understanding crime, deviance, false memories, confessions and testimonies. Leaving high school with distinctions, I knew I wanted to get involved in some aspect of psychology and law, and thus enrolled in an undergraduate psychology degree.

"As a young girl I wanted to be a detective, and my friends and I used to create fake crime scenes, pretend we were the FBI, and set off to solve the mysteries. I think we grew up in the era of [crime-solving television series] CSI Miami and other shows, so it was exciting to be a detective."

Now she gets to work side by side with the SAPS for some of her field studies, particularly with the SAPS Investigative Psychology Unit.

"This is something I love doing," says Kempen, who is the first person in her family to get a degree. She is also a National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS) student – NSFAS is the South African government student loan and bursary scheme – and she knows all about taking on extra work to make ends meet in order to be able to follow her dream. Right now, that dream is to ensure that innocent people aren't locked up for crimes they didn't commit.

Story by Vivian Warby. Black-and-white facial composite constructed using FACES 4.0, by IQ Biometrix. Individual feature line-ups courtesy of Kate Kempen.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.