The dark side of the universe

07 November 2014 | Story by Newsroom

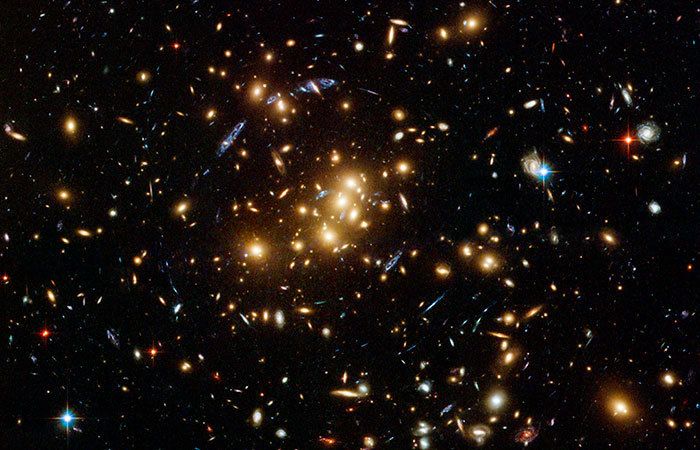

Over the last fifty years, astrophysicists' concept of the universe and what it is made of has radically changed. We draw conclusions about the universe through our study of its light. Through that study of light, astrophysicists have discovered that most of the universe is dark. The stuff we can see with our eyes makes up only 5% of the universe. The remaining 95% is the "dark sector", consisting of what astrophysicists call "dark matter"(25%) and "dark energy" (70%).

Dark matter has mass but doesn't interact with light. Dark energy is responsible for the accelerating expansion rate of the universe. Astrophysicists do not know what either of these substances are. In fact, many would argue that the dark sector doesn't exist, and that it only results from our misunderstanding of the laws of physics such as Einstein's theories of relativity.

From 17 and 22 November, UCT's Astrophysics, Cosmology and Gravity Centre (ACGC) will host a major international conference, the Dark Side of the Universe, bringing together leading experts in dark matter and dark energy from around the world. Understanding the dark side of the universe is one of the key fundamental science questions in physics and cosmology, and it may possibly lead to theories beyond the standard models of particle physics and Big Bang cosmology.

This meeting is in the series of the DSU workshops previously held in Seoul (2005), Madrid (2006), Minnesota (2007), Cairo (2008), Melbourne (2009), Leon (2010), Beijing (2011), Buzios, Rio de Janeiro (2012) and Trieste (2013).

In addition to the main scientific programme, there will be two public events:

- Cosmic Africa: A personal journey

A public lecture by Professor Thebe MedupeWhen Halley's comet passed near the earth in 1986, it sparked off Thebe Medupe's interest in astronomy. At the age of thirteen, he built his first telescope and made his own map of the moon in a small South African village near Mafikeng. After matriculating at Mmabatho High School, he proceeded to study physics and astronomy at the University of Cape Town. It was here that he earned his MSc (cum laude) in astrophysics. He has obtained his doctorate in astrophysics from the University of Cape Town (December 2002), to become one of the first three black South African astronomers.

Now an associate professor at the North West University (Mafikeng Campus) – where he researches the use of sound waves to probe the interiors of pulsating stars – Medupe's became part of the film called Cosmic Africa in which he visited remote villages in Africa, searching for ordinary villager's knowledge about the night sky.

Join him on Monday 17 November at 18h00 in the New Science Lecture Theatre at UCT for a journey to the San of Tshumkwe, Namibia as they attempt to come to terms with the solar eclipse, the Dogons of Bandiagara in Mali as they speak their calendar systems, and the "Stonehenge of Africa" in Nabta Playa, south of Egypt in the Sahara. - Does the Dark Universe exist?

A debate among leading astrophysicistsThis event – on Thursday 20 November at 19h00 at the University of the Western Cape's Life Sciences Auditorium – brings together leading researchers to debate the nature and very existence of the Dark Universe. Debaters include:

- Associate Professor Gianfranco Bertone from the University of Amsterdam, whose research tackles some of the most fundamental questions in Cosmology: What is Dark Matter? Can we detect it in our laboratories? Can we produce it in our particle accelerators?

- Prof Romeel Dave, the SARChI Chair in Cosmology at the University of the Western Cape, whose research focuses on modelling the universe on supercomputers, from the Big Bang until today.

- Prof Ruth Durrer, director of the Theoretical Physics Department at Geneva University.

- Cosmologist Prof Jean-Philippe Uzan, deputy director of the Institut Henri Poincare, who has worked on the shape of the universe, the origin of structures, the nature of the laws of physics, the constants of nature, and the nature of dark energy. He's also written several popular science books, and been involved in projects at the border between science and arts such as a theatre play on infinity and a musical installation on our universe.

For more details, visit the conference website or contact Professor Peter Dunsby at peter.dunsby@uct.ac.za or 071 671 9195.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.