Translating Yeats into music like 'creating a garment for a specific body'

27 October 2014 | Compiled Abigail Calata. Photo Je'nine May.

Professor Hendrik Hofmeyr explains the creative process behind translating WB Yeats' Byzantium '“ a poem that in itself is a metaphor for the creative process '“ into music.

Describing the creative process can be daunting, yet this is precisely the challenge Professor Hendrik Hofmeyr, head of composition and theory at the South African College of Music, took on when delivering his inaugural lecture on 2 October 2014 at the Baxter Concert Hall.

Hofmeyr began with a disclaimer (of sorts):

"In my experience, there are few conversation killers as deadly as a composer being asked by a well-meaning hostess to tell the company about his work. I am therefore perhaps foolhardy in having chosen as the subject of my lecture the way in which I as composer interact with a literary text in setting it to music."

Hofmeyr used WB Yeats' Byzantium '“ which he describes as "one of the most fascinating [poems] in the English language" '“ as the basis for a symphonic tone poem for voice and orchestra. His aim was "to create a musical equivalent of the poem, both in terms of structure and meaning".

He likened the process of setting literature to music to "creating a garment for a specific body: the creator may choose to follow the underlying structure at times closely and at times loosely, may emphasise certain things and conceal others, may at times be guided by function and times by aesthetic considerations or by the characteristics of his material. Both the body and the garment should be well made, but the success of the enterprise depends on the mutually beneficial interaction between the two."

Citing literary critic Walter Pater, Hofmeyr said that his task was made easier by the fact that Byzantium already "aspires to the conditions of music".

"The work is in fact almost symphonic in character, not only in the grandeur of its conception, style and imagery, but also in the almost incantatory use of recurrent words, images and ideas."

Hofmeyr quoted from Yeats' esoteric work A Vision to evince his fascination with the culture of the city of Byzantium (modern-day Istanbul):

I think that in early Byzantium, and maybe never before or since in recorded history, religious, aesthetic and practical life were one, and that architect and artificers ' spoke to the multitude and the few alike. The painter and the mosaic worker, worker in gold and silver, the illuminator of the Sacred Books were almost impersonal, almost perhaps without the consciousness of individual design, absorbed in their subject matter and that [Stet] the vision of a whole people.

According to Hofmeyr, the city, and more specifically the famous domed cathedral of Hagia Sophia, symbolise "a perfected afterlife". The poem depicts "how the souls of the dead arrive in the holy city to be transmuted into flames of spiritual fire in the imperial smithies" '“ and can also be seen as a metaphor for the creative process itself: "The souls purified and refashioned in the Emperor's smithies to attain immortality can be seen as markers for the experiences and perceptions that have to be distilled [by the artist] to extract their aesthetic essence and transmute them from the personal to the universal".

At the centre of the poem '“ and of its setting to music '“ are three themes, "man, the smithies and the dome," representing "mortality, transmutation and immortality". In Hofmeyr's music, the theme of man is introduced at the outset in an expressive cello solo. It is interrupted by the full orchestra with the noisy theme of the smithies, "fashioned from fragments of the theme of man, which is broken up, as the '˜complexities of mire and blood' are broken up by the smithies, and re-assembled through somewhat arcane musical procedures ... employed here as a musical symbol of the fabled craftsmanship of the Byzantine goldsmiths".

The theme of immortality, introduced at the words "A starlit or a moonlit dome", is again based on transmuted motifs from the theme of man, "but now circling serenely around a central pitch". The second and third stanzas of the poem deal with the two paths to perfection in Yeats' esoteric system of spiritual evolution, designated respectively as the starlit and the moonlit phase.

The moonlit phase represents perfect plasticity (or life-in-death) and is symbolised by a guiding spectre, rather like Virgil in Dante's Divine Comedy, depicted in the music by an eerie instrumental texture derived from the incomplete dome theme and "floating in a kind of musical limbo".

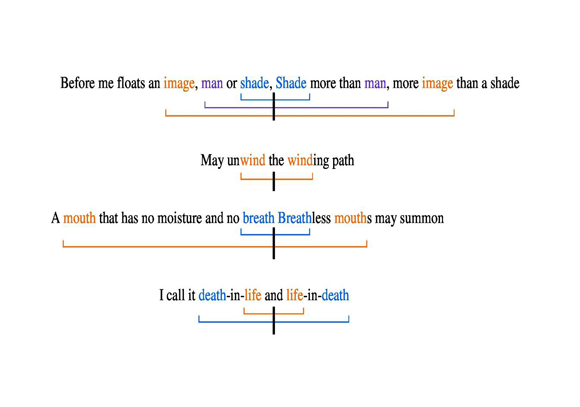

A crowing golden bird of the type for which the Byzantine goldsmiths was particularly renowned symbolises the starlit phase, representing perfect form (or death-in-life). Its music is refined from the elements of the smithies theme. These two symbols are linked by a quatrain (a stanza of four lines) which makes it clear that they represent the superhuman state. The text features curious mirrorings, which lead up to a perfect palindrome (a phrase that reads the same backward as forward) at "I call it life-in-death and death-in-life":

At "a mouth that has no moisture and no breath breathless mouths may summon", this mirroring is reflected in the orchestral writing, which is reduced to "a kind of desiccated four-part mirror canon ... in which each new entry inverts the preceding". A canon is a piece of music in which two or more voices (or instrumental parts) sing or play the same music, starting at different times.

The canon introduces a new motif representing the superhuman, and in the final two stanzas the two opposing elements of this motif are integrated to form the motif associated with the flames of spiritual fire. In the flitting dance of these flames, which forms the basis of the musical fabric from this point onwards, all the themes of the work are alloyed and transmuted as in a purifying furnace, explained Hofmeyr

The lecture concluded with Hofmeyr playing a recording of the music, accompanied by slides illustrating the intricate relationship between poetic and musical symbols.

Listen to the audio recording of Prof Hofmeyr's lecture.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.