Debunking the myth that there was no technology in Africa before colonialism

08 October 2014 | Story by Newsroom

Listen to Dr Shadreck Chirikure explain how indigenous systems have been incorporated into today's technology and why it is believed that African civilisation has made no contribution to technological developments in an interview on Heritage Day on SAFM.

Dr Shadreck Chirikure seeks to debunk the myth that there was no science and technology in Africa before colonialism. The most important challenge in this research is that most of the dominant frameworks were not constructed using African experiences, and were incorporated locally without much modification. This calls for new perspectives informed by the African experience or local knowledge. "Most knowledge is acquired in a Western way; but before then, what were Africans doing?" he asks. "How much do we know about the mining that was being done, about the spears that made Shaka Zulu so successful?"

It is no surprise that Chirikure, a senior lecturer in the Department of Archaeology, was on the Mail & Guardian's 2013 list of 200 Young South Africans, singled out for his contribution to changing the way Africans think about their own continent. With a doctorate in archaeology, Dr Chirikure focuses primarily on pre-colonial technology in indigenous mining and metalworking in Africa. "I combine archaeological, anthropological and historical approaches with standard metallurgical and mineralogical techniques to investigate pre-colonial metal extractive technologies and the associated socio-cultural processes," he says.

And it appears to be an approach that is working. He has turned up many revelatory findings in his research career, including the fact that not only were Southern Africans prospecting and mining to extract metals to use locally long before the colonial era, but they were also exporting the knowledge to China and to countries on the Indian Ocean.

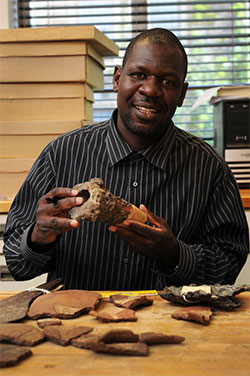

Dr Shadreck Chirikure.

Dr Shadreck Chirikure.

Currently, Dr Chirikure is investigating the contributions of metallurgy to early state formation and inter-continental contact in Southern Africa. Using the Shona concept of rotational succession, where power moves between 'houses' or brothers upon the death of the incumbent king or chief, he and his collaborators have argued that there were many centres, rather than one major capital, in the region. He has initiated a project at the archaeological site of Mapela in Zimbabwe, long believed to be a subsidiary within the grand state of Mapungubwe. The last archaeologist to work at Mapela was Peter Garlake, in 1966. New excavations are indicating that Mapela was much bigger than previously thought. It has yielded thousands of glass beads, which suggests that it was a thriving trade centre. This work is a collaborative project with researchers from the UK, Botswana and Zimbabwe.

Dr Chirikure has also just been awarded a National Research Foundation (NRF) Blue Skies grant to study Great Zimbabwe, Mapungubwe and other related places, to explore new models for (and evaluate the contribution of metals to) nascent urbanism in the region. In this work he will draw on the expertise of Professor Sue Parnell (African Centre for Cities) on African urban systems, while professors John Compton (Geological Sciences) and Mike Meadows (Environmental and Geographical Science) will offer guidance on the contributions of climate change to state formation.

Dr Chirikure came to UCT as a postdoctoral fellow in 2007. He was enrolled into the Emerging Researcher Programme (ERP) early in his academic career, working with the coordinator for the science, engineering and technology stream at the time, Dr Dianne Bond. For Dr Bond, three things stand out as she recalls her encounters with Dr Chirikure: her immediate sense that here was someone who was clearly going places, the fact that he availed himself of the opportunities provided by the ERP for new staff members, and his constant gratitude for the tools, notably in the form of research-related information, that smoothed his path in developing a robust research profile.

Aside from being recognised in the Mail & Guardian list, Dr Chirikure has been awarded a Mandela Mellon Fellowship, enabling him to spend time at Harvard University, and was invited by Cambridge University Press to write a book on his research. He also sits on the editorial boards of three journals, is a founding member of the South African Young Academy of Science, and received a prestigious P-rating from the NRF in 2012.

Apparently, Dr Chirikure was once so shy he was afraid to look his lecturers in the eye. Now he is an outspoken campaigner for African research. This year he was appointed Research Associate of the Programme for the Enhancement of Research Capacity (PERC). In this capacity, he supports PERC's work to develop the research careers of mid-career academic staff at UCT, specifically encouraging the development of research initiatives that reflect the university's location in Africa and in a more broadly developing context. In May 2013, he convened a round-table discussion on Afropolitan Research Opportunities and Constraints: Creating knowledge for transforming and empowering Africa.

"Africa is promising in that there are so many avenues that can be explored, thereby transforming the continent into a competitive global knowledge producer," he says.

Photo of Dr Shadreck Chirikure by Michael Hammond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.