Ancient DNA of marine hunter-gatherer sheds light on our common ancestry

07 October 2014 | Story by Newsroom

A man who lived 2 330 years ago on the southernmost tip of Africa belonged to the earliest group of humans to diverge from 'Mitochondrial Eve', our common ancestor.

When archaeologist Andrew Smith, an emeritus associate professor at UCT, discovered a skeleton at St Helena Bay in 2010, he immediately recognised the significance of his finding. He contacted Professor Vanessa Hayes, a world-renowned expert in African genomes now at Australia's Garvan Institute of Medical Research in Sydney.

Hayes assembled a team of international experts to help her analyse the genetics of the skeleton, including paleogeneticist Professor Svante Pääbo at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, the world's leading laboratory in ancient DNA research.

Using DNA extracted from a tooth and a rib (a difficult operation, given the acidity of the soil), the genetics team generated a complete mitochondrial genome for the man. Mitochondrial DNA is passed from mother to child, and provided the first evidence that we all come from Africa and share a common ancestor, known as 'Mitochondrial Eve', who lived around 200 000 years ago in Africa. The DNA profile of the St Helena skeleton revealed that he belonged to one of the earliest groups of humans to diverge from this common ancestor.

"We were thrilled that Andrew Smith understood the importance of not touching the skeleton when he found it, and so did not contaminate its DNA with modern human DNA," said Professor Hayes.

UCT biological anthropologist Professor Alan Morris, one of the lead authors of a paper now published in the journal Genome Biology and Evolution, undertook the physical analysis of the skeleton itself. "He used his skills in forensics and murder cases to assemble a profile of the man behind the St Helena skeleton," says Hayes.

Forensic anthropology is the application of the knowledge of skeletal biology to medico-legal cases. "The data and methods of analysis are almost identical, whether the skeleton is 5 000 years old or from six months ago," says Morris. "Part of any analysis is the reconstruction of events at death (which are not really visible in this archaeological case), but also the life history of the person. In forensics it is used to establish the identity of the individual, but in archaeology it helps to tell us something about the community from which the individual was drawn."

Tooth wear places the man in his fifties. (Photo courtesy of Alan Morris.)

Tooth wear places the man in his fifties. (Photo courtesy of Alan Morris.)

Osteoarthritis and tooth wear placed the St Helena man in his fifties. Apart from the wear, however, his teeth were in perfect condition; this also suggested that he was a hunter-gather, since there is little natural sugar in the hunter-gatherer diet.

A bony growth in the ear canal showed that the man suffered from 'surfer's ear', which can develop when the head is repeatedly immersed in cold water. "The body reacts to the cold water by laying down extra layers of bone inside the auditory meatus (the ear canal)," explains Morris. "Over time, this reduces the width of the canal and can cause complications. Surfers know it well."

Surfer's ear has been documented in archaeological cases along the California West Coast, and in other places. "The St Helena man is most likely to have developed it from gathering shellfish in the surf zone, or tidal pools," says Morris. Shells found near his grave were carbon-dated to the same period, which confirmed his seafood diet.

The identification of the man as a marine hunter-gatherer '“ in contrast to the contemporary inland hunter-gatherers from the Kalahari desert '“ raised questions about how the two were related. The St Helena skeleton carried a different maternal lineage to the pastoralists who migrated down the coast from Angola 2 000 years ago, and probably represents the 'aboriginal' (or indigenous) genome in the Cape region. "It contains a DNA variant that we have never seen before," says Hayes. "Because of this, the study gives a baseline against which historic herders at the Cape can now be compared."

The study underlines the significance of southern African archaeological remains in defining human origins. Professor Hayes is especially keen for Africa to inform genomic research and medicine worldwide.

"One of the biggest issues at present is that no-one is assembling genomes from scratch '“ in other words, when someone is sequenced, their genome is not pieced together as is," she said.

"Instead, sections of the sequenced genome are mapped to a reference genome. Largely biased by European contribution, the current reference is poorly representative of indigenous peoples globally. If we want a good reference, we have to go back to our early human origins.

"In this study, I believe we may have found an individual from a lineage that broke off early in modern human evolution, and remained geographically isolated. That would contribute significantly to refining the human reference genome."

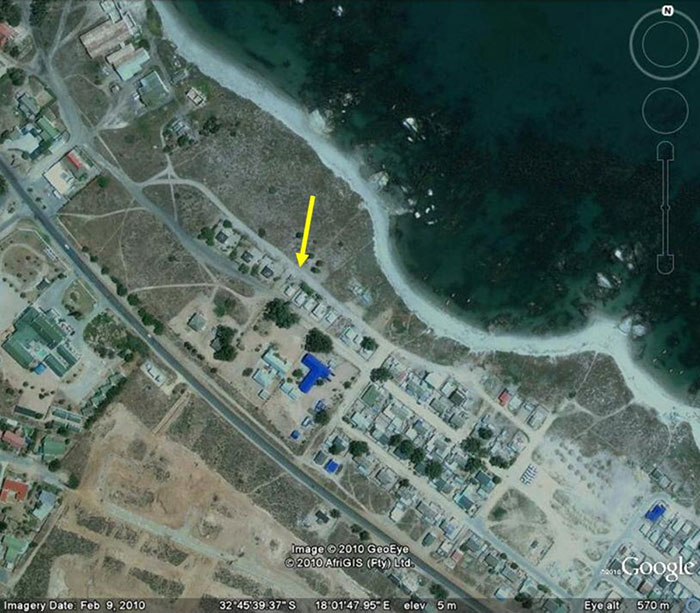

The yellow arrow shows the location of the skeleton in St Helena Bay, indicating how close he was found to the shoreline. (Photo courtesy of Google Maps.)

The yellow arrow shows the location of the skeleton in St Helena Bay, indicating how close he was found to the shoreline. (Photo courtesy of Google Maps.)

Story by Carolyn Newton, based partly on a press release by the Garvan Institute.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.