Let culture and nature redraw African boundaries

10 July 2014 | Story by Newsroom

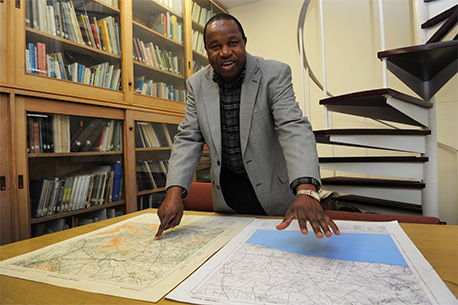

All over the world boundaries are shifting and maps are being redrawn. In Africa, transnational parks have redefined state borders for wildlife and could do more to decolonise the continent, says UCT's Environmental and Geographical Science Associate Professor Maano Ramutsindela in an op-ed published in the New York Times Sunday Review's Room for Debate section earlier this week:

The partitioning of Africa by European empires has had devastating social, economic, political and psychological impacts, and millions of lives have been lost in post-independence Africa defending colonial borders. We are overdue for an African renaissance, completing the decolonization '“ which remains unfinished business until boundaries are changed.

Africans and others have proposed many new maps of Africa. One recurring idea is to carve up the continent into smaller states on the basis of ethnicity or its proxies, like shared language. This theory has been put into practice in the new state of South Sudan, which now faces serious existential challenges. Other proposals have focused on creating larger states that would balance power among disparate groups, but this repeats the colonial mistake of imposing boundaries onto people.

There is a more promising approach, however. The conservation lobby and its financiers have been keen to create transnational parks, to re-establish and protect ecological systems that span the boundaries of contiguous states. The idea is a not unique to the continent, but they mushroomed in southern Africa after the end of apartheid in South Africa. So far these parks have redefined state borders for wildlife but not for people. But if the project went further, it could radically decolonize Africa '“ allowing micro-regions to inspire a new map.

Conservationists currently encourage some visits among people, but for real decolonization the short-term goal should be fluid movement of people within transfrontier parks and around transborder natural resources. For example, the Kgalagadi, the first official transfrontier park in post-independence Africa, is the historical home of the southern San community in Botswana, Namibia and South Africa. The San - part of the Khoe-San language group - struggle to cross borders to work and visit family, even though wildlife and tourists roam freely in the park, entering all three nations. Even without redrawing the borders of Botswana, Namibia and South Africa, the nations could acknowledge that the Kgalagadi micro-region represents the land of the San. They should think of themselves, and live their lives, as transnational citizens.

Micro-regions evolve from existing connections and ecosystems. They can be formalized as transnational conservation areas, or they can be informal if governments are hesitant. The development and recognition of micro-regions is good for humans and ecosystems, because it gives local residents (on both sides of the border) a collective voice in governing the natural resources. As more micro-regions are established and respected, they will be a stepping stone toward regional integration in southern Africa.

People living in Africa's borderlands have long used colonial borders as theaters of opportunities. Transnational parks create yet another opportunity: for conservation, for decolonization, for an African renaissance.

Prof Maano Ramutsindela's op-ed first appeared in the New York Times Sunday Review's Room for Debate on 4 July 2014.

Image by Michael Hammond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.